Difference between revisions of "399: Travelling Salesman Problem"

(Undo revision 55576 by 108.162.219.220 (talk) Not helpful to a compete comic.) |

(Corrected remarks about efficiency of solutions to travelling salesman problem, and made discussion of the problem slightly more precise.) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

| − | The {{w|Travelling salesman problem}} is a classic problem in computer science that given a list of cities and their pairwise distances, the task is to find the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and returns to the origin city. A naive solution solves the problem in {{w|Factorial|n! time}} (where n is the size of the list), simply by checking all possible routes, and selecting the shortest one. | + | The {{w|Travelling salesman problem}} is a classic problem in computer science. An intuitive way of stating this problem is that given a list of cities and their pairwise distances, the task is to find the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and then returns to the origin city. A naive solution solves the problem in {{w|Factorial|O(n!) time}} (where n is the size of the list), simply by checking all possible routes, and selecting the shortest one. A more efficient {{w|Dynamic programming|dynamic programming}} approach yields a solution in O(n<sup>2</sup>2<sup>n</sup>) time. |

The joke is that the computer salesman selling on {{w|eBay}} does not have to worry about this problem since he does not need to travel, to which the travelling salesman angrily responds "shut the hell up". | The joke is that the computer salesman selling on {{w|eBay}} does not have to worry about this problem since he does not need to travel, to which the travelling salesman angrily responds "shut the hell up". | ||

Revision as of 10:57, 27 December 2013

Explanation

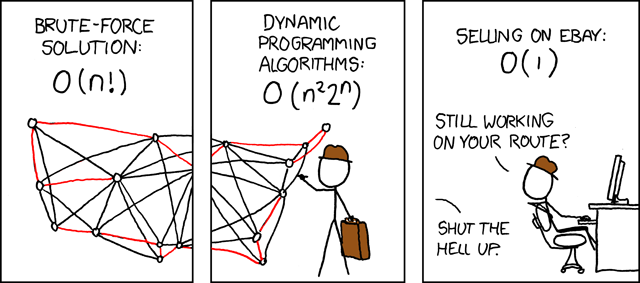

The Travelling salesman problem is a classic problem in computer science. An intuitive way of stating this problem is that given a list of cities and their pairwise distances, the task is to find the shortest possible route that visits each city exactly once and then returns to the origin city. A naive solution solves the problem in O(n!) time (where n is the size of the list), simply by checking all possible routes, and selecting the shortest one. A more efficient dynamic programming approach yields a solution in O(n22n) time.

The joke is that the computer salesman selling on eBay does not have to worry about this problem since he does not need to travel, to which the travelling salesman angrily responds "shut the hell up".

The title text wonders about the time complexity of the Cutting-plane method, which is sometimes used to solve optimization problems. The last sentence suggests the down side for Randall of writing comics about computer science; he sometimes encounters problems to which he cannot find the answer, whereas authors of simpler comics such as Garfield do not have this problem. This is also likely a reference to 78: Garfield, which parodies Garfield's simplicity.

This is so far the only comic featuring the Brown Hat character.

Also see previous strip 287: NP-Complete.

Transcript

- [There is a linked black web, with a path in red; it may be a map of the USA.]

- Brute-force solution:O(n!)

- [The web continues in this one. A man with a hat and a case is drawing it.]

- Dynamic programming algorithms: O(n22n)

- [Another man, with a hat too, is at a computer, looking back over the chair.]

- Selling on eBay: O(1)

- Computer salesman: Still working on your route?

- Drawing salesman: Shut the hell up.

Discussion

Does anyone remember if the Brown Hat appears in any other comics?

- I'm not sure, so I created a category and page for him, let's see if that catches any others. --Jeff (talk) 22:04, 29 March 2013 (UTC)

- According to the transcript we have two different Brown Hat Guys here. I'm working on this.--Dgbrt (talk) 21:49, 5 October 2013 (UTC)

- I'm inclined to think that Brown Hat is specific to this comic, the brown hat being the 50's style homburg or fedora common to salesmen trying to look respectable... Randall likely added the hats to depict folks from a bygone era, (one of whom has caught up with the trend.) -- IronyChef (talk) 01:49, 10 January 2014 (UTC)

- The second Brown Hat Guy seems similar to Black Hat both in personality and hat shape. Could he be the same character? Richmond tudor (talk) 03:22, 13 March 2015 (UTC)

- According to the transcript we have two different Brown Hat Guys here. I'm working on this.--Dgbrt (talk) 21:49, 5 October 2013 (UTC)

It's probably not in the least important, but the network appears to be a collection of key cities in the US arranged by geographical location. 130.160.145.185 23:07, 9 March 2013 (UTC)

added a better explanation of the title text. -- Nick,5 Oct 2013 69.193.7.67 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Has anyone answered the question in the title text? --Ricketybridge (talk) 23:55, 9 January 2014 (UTC)

- "it is bitter news that in the forty years since Held and Karp no better guarantee [than n^2.2^n] has been found for the problem" [1]. So whereas linear programming techinques tend to be quicker than other algorithms, they have not been shown to be better than O(n^2.2^n).141.101.98.55 17:05, 17 August 2014 (UTC)

Doesn't someone at ebay still have to solve the TSP? I guess that's the entire point though. 141.101.85.223 08:48, 27 July 2014 (UTC)

- No because you can send your sales information to all customers at once because they come to you, electronically. It takes no longer for you to be viewed by 100 people than by one person. Thus O(1). 141.101.98.55 17:05, 17 August 2014 (UTC)

- I never used ebay so I don't know how it works and I'm probably missing something obvious. (Maybe it should be explained at the explanation?) If you wanted to personally sell about 17 items to 17 cities like the guy on the left, you have to visit each city by car or something. How does ebay visit the 17 cities to send the items?141.101.85.199 06:34, 19 August 2014 (UTC)

- You don't have to personally visit each buyer. You put a description of the item(s) you are selling online on eBay, and then people can decide to buy or not. If they do buy, they pay you online, any communication is done online, and you send them the item(s) in the mail. I don't think its necessary to have an explanation of how eBay works, as the majority of people would know. --Pudder (talk) 16:31, 8 December 2014 (UTC)

- I never used ebay so I don't know how it works and I'm probably missing something obvious. (Maybe it should be explained at the explanation?) If you wanted to personally sell about 17 items to 17 cities like the guy on the left, you have to visit each city by car or something. How does ebay visit the 17 cities to send the items?141.101.85.199 06:34, 19 August 2014 (UTC)

Oh god, wish I could vote this up... somehow... 108.162.219.108 15:43, 11 June 2015 (UTC)

It is curious that nobody here appears to have noticed that O(n!) is equivalent to O(n log(n)). Last time I checked, I seem to recall finding that O(n log(n)) was under O(n^2), and therefore under O(n^2.2^n). Or have I missed something? Certainly the worst-case can't be over O(n log(n)), as this is the class of the number of ways to sort a list of the cities. So, then, the O(n^2.2^n) must be better by some other multiplier. Come to that, O(n^2.2^n) seems to be within O(2^n). What am I missing here? 108.162.250.134 22:27, 9 August 2015 (UTC)

- I find it more curious that you think O(n!) is equivalent to O(n log(n))… it most certainly isn’t. O(n log(n)) is (provably) the optimal complexity of a Comparison sort; O(n!) is the complexity of Bogosort, one of the stupidest sorting algorithms imaginable. —162.158.90.162 21:23, 23 August 2015 (UTC)

- This is so, but when one examines the theory of big O notation, one finds that they are mathemticaly equivalent. The point, therefore, is that the difference is purely in form. To illustrate: A list has O(n!) permutations possible. A sorting algorithm can therefore never sort a worst-case random list with less than O(n!) comparisons, as this is the minimum required to get the list in the correct order for the best case, when we assume the worst possible list for the algorithm. It is possible to prove that O(n!) is O(n log(n)) re-expressed. Therefore the difference seems merely to exist to highlight the general behaviour to humans. Agreed, however, that until the advent of the wavefunction-based "quantum" computer, the bogosort is as bad as it gets. This does not change the fact that any comparison sort must distinguish between O(n!) lists, and therefore can never do that with less than O(n! -1)=O(n!) comparisons. The proof of the n log n barrier rests on this, and n log n is merely a nicer-looking way of writing n! here. Unless I have encountered a flawed proof, this should hold, and even then, the number of possibilities that must be distinguished should bound it... Provided of course that this idea, too, is not logically flawed. If so, how, and if not, then why the notation? Is this somehow applying the same logic that distinguishes a binary sort from a linear one to the set of possible orderings? If so, it must be functionally pre-sorted, by some logic... Where have I erred, if I have erred, and, should I have erred, how might the correct solution be explained?

- 108.162.249.183 11:21, 2 September 2015 (UTC)

- > It is possible to prove that O(n!) is O(n log(n)) re-expressed.

- Then prove it.

- > any comparison sort must distinguish between O(n!) lists, and therefore can never do that with less than O(n! -1)=O(n!) comparisons.

- This suggests to me that you've never written a comparison sort. Here's merge sort in JS:

window.comparisons = 0;

function merge_sort(arr) {

if(arr.length <= 1) {return arr;}

var left = merge_sort(arr.slice(0, Math.floor(arr.length / 2)));

var right = merge_sort(arr.slice(Math.floor(arr.length / 2)));

var lp = 0;

var rp = 0;

for(var ap = 0; ap < arr.length; ap++) {

window.comparisons++;

if(rp >= right.length || (lp < left.length && left[lp] < right[rp])) {

arr[ap] = left[lp];

lp++;

}

else {

arr[ap] = right[rp];

rp++;

}

}

return arr;

}

console.log(merge_sort([5, 4, 3, 2, 1]), comparisons); //12; log2(5) is 2.3, ceil(2.3 * 5) == 12; 5! is 120

window.comparisons = 0;

var arr = [];

for(var i = 0; i < (1 << 16); i++) {arr[i] = (1 << 16) - i;}

console.log(arr); //1 through 65536

console.log(merge_sort(arr), comparisons); //1,048,576; log2(65536) is 16, ceil(16 * 65536) == 1,048,576; 65536! is 5*10^287193

- If what you said was true, modern computer science would collapse. Even if you don't believe me, you have to concede that the mere fact you can sort 65536 things before the heat death of the universe is proof that you did the math wrong. 173.245.54.28 03:42, 19 November 2015 (UTC)

- 1) I think you might be confused on how math works. n! refers to factorial (1*2*3...n). n log n is n multiplied by the logarithm of n.

- 2) Didn't read all of the rambling, but it seems like you believe a list can only be sorted by brute-force, going over each item and comparing it to the rest of the list. This would in fact be n!. Most sorting algorithms do not use the brute force method since humans are built to recognize patterns and come up with algorithms regarding those patterns. Flewk (talk) 01:13, 28 December 2015 (UTC)

- Actually, it's not O(n!) that is equivalent to O(n log(n)), but O(log(n!)) is. See Stirling formula for details.

- Seems your memory just dropped that log. 198.41.242.245 08:57, 27 June 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you to all of ye helpful contributors. I am not sure what led me to write the seed of this (tiredness?), but it is, as noted, a complete and steaming pile of rubbish. Duty Calls, and so forth. I hope I have inadvertently amused someone. Possibly this is a result of abstract mathematics being learned at around four layers of abstraction. Have a good day/night. 162.158.58.141 09:35, 26 December 2016 (UTC)

Running time of Dynamic Programming has changed

BTW The running time the dynamic programming solution, O(n^2 2^n) should be changed now: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.03018 -- Mihail.stoian (talk) 19:21, 8 May 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)