1132: Frequentists vs. Bayesians

Explanation[edit]

This comic is a joke about jumping to conclusions based on a simplistic understanding of probability. The "base rate fallacy" is a mistake where an unlikely explanation is dismissed, even though the alternative is even less likely. In the comic, a device tests for the (highly unlikely) event that the sun has exploded. A degree of random error is introduced, by rolling two dice and lying if the result is double sixes. Double sixes are unlikely (1 in 36, or about 3% likely), so the statistician on the left dismisses it. The statistician on the right has (we assume) correctly reasoned that the sun exploding is far more unlikely, and so is willing to stake money on his interpretation.

The labels given to the two statisticians, in their panels and in the comic's title, are not particularly fair or accurate, a fact which Randall has acknowledged:[1]

I seem to have stepped on a hornet’s nest, though, by adding “Frequentist” and “Bayesian” titles to the panels. This came as a surprise to me, in part because I actually added them as an afterthought, along with the final punchline. … The truth is, I genuinely didn’t realize Frequentists and Bayesians were actual camps of people—all of whom are now emailing me. I thought they were loosely-applied labels—perhaps just labels appropriated by the books I had happened to read recently—for the standard textbook approach we learned in science class versus an approach which more carefully incorporates the ideas of prior probabilities.

The "frequentist" statistician is (mis)applying the common standard of "p<0.05". In a scientific study, a result is presumed to provide strong evidence if, given that the null hypothesis, a default position that the observations are unrelated (in this case, that the sun has not gone nova), there would be less than a 5% chance of observing a result as extreme. (The null hypothesis was also referenced in 892: Null Hypothesis.)

Since the likelihood of rolling double sixes is below this 5% threshold, the "frequentist" decides (by this rule of thumb) to accept the detector's output as correct. The "Bayesian" statistician has, instead, applied at least a small measure of probabilistic reasoning (Bayesian inference) to determine that the unlikeliness of the detector lying is greatly outweighed by the unlikeliness of the sun exploding. Therefore, he concludes that the sun has not exploded and the detector is lying.

A real statistician (frequentist or Bayesian) would probably demand a lower p-value before concluding that a test shows the Sun has exploded; physicists tend to use 5 sigma, or about 1 in 3.5 million, as the standard before declaring major results, like discovering new particles. This would be equivalent to rolling between eight and nine dice and getting all sixes, although this is still not "very good" compared to the actual expected likelihood of the Sun spontaneously going nova, as discussed below.

The line, "Bet you $50 it hasn't", is a reference to the approach of a leading Bayesian scholar, Bruno de Finetti, who made extensive use of bets in his examples and thought experiments. See Coherence (philosophical gambling strategy) for more information on his work. In this case, however, the bet is also a joke because we would all be dead if the sun exploded. If the Bayesian wins the bet, he gets money, and if he loses, they'll both be dead before money can be paid. This underlines the absurdity of the premise and emphasizes the need to consider context when examining probability.

It is also possible that the use of the sun is a reference to Laplace's Sunrise problem.

The title text refers to a classic series of logic puzzles known as Knights and Knaves, where there are two guards in front of two exit doors, one of which is real and the other leads to death. One guard is a liar and the other tells the truth. The visitor doesn't know which is which, and is allowed to ask one question to one guard. The solution is to ask either guard what the other one would say is the real exit, then choose the opposite. Two such guards were featured in the 1986 Jim Henson movie Labyrinth, hence the mention of "A LABYRINTH GUARD" here. A labyrinth was also mentioned in 246: Labyrinth Puzzle.

Further a less serious mathematical exploration[edit]

As mentioned, this is an instance of the base rate fallacy. If we treat the "truth or lie" setup as simply modelling an inaccurate test, then it is also specifically an illustration of the false positive paradox: A test that is rarely wrong, but which tests for an event that is even rarer, will be more often wrong than right when it says that the event has occurred.

The test, in this case, is a neutrino detector. It relies on the fact that neutrinos can pass through the earth, so a neutrino detector would detect neutrinos from the sun at all times, day and night. The detector is stated to give false results ("lie") 1/36th of the time.

There is no record of any star ever spontaneously exploding—they always show signs of deterioration long before their explosion—so the probability is near zero. For the sake of a number, though, consider that the sun's estimated lifespan is 10 billion years. Let's say the test is run every hour, twelve hours a day (at night time). This gives us a probability of the Sun exploding at one in 4.38×1013. Assuming this detector is otherwise reliable, when the detector reports a solar explosion, there are two possibilities:

- The sun has exploded (one in 4.38×1013) and the detector is telling the truth (35 in 36). This event has a total probability of about 1/(4.38×1013) × 35/36 or about one in 4.50×1013

- The sun hasn't exploded (4.38×1013 − 1 in 4.38×1013) and the detector is not telling the truth (1 in 36). This event has a total probability of about (4.38×1013 − 1) / 4.38×1013 × 1/36 or about one in 36.

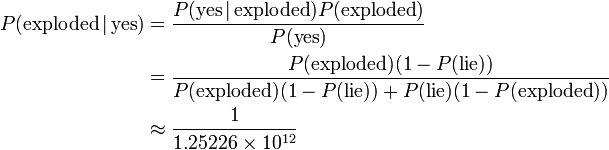

Clearly the sun exploding is not the most likely option. Indeed, Bayes' theorem can be used to find the probability that the Sun has exploded, given a result of "yes" and the prior probability given above:

Transcript[edit]

- [Caption above the first panel:]

- Did the sun just explode?

- (It's night, so we're not sure)

- [Two Cueball-like guys stand on either side of a small table with a small black device on it. The device has white lines (ventilation) and two small antennas and a button on top. When the device speaks it uses in Westminster typeface. The Guy on the left, called Frequentist Statistician in the 2nd panel, points to the device. The guy on the right, called Bayesian Statistician in the 3rd panel, is just looking at the device. Above the spoken word from the device is a sound.]

- Frequentist Statistician: This neutrino detector measures whether the sun has gone nova.

- Bayesian Statistician: Then, it rolls two dice. If they both come up as six, it lies to us. Otherwise, it tells the truth.

- Frequentist Statistician: Let's try. Detector! Has the sun gone nova?

- Sound:Roll

- Device: YES.

- [Two panels side by side are beneath the first panel. together they are broader than the top panel. Above each panel is a caption. In the left panel only the left statistician is shown with the device on the table. And in the right panel only the right statistician is shown with the device on the table. both are just looking at the device.]

- Frequentist Statistician:

- Frequentist Statistician: The probability of this result happening by chance is 1/36=0.027. Since p<0.05, I conclude that the sun has exploded.

- Bayesian Statistician:

- Bayesian Statistician: Bet you $50 it hasn't.

Trivia[edit]

- The Sun will never explode as a supernova, because it does not have enough mass to undergo core collapse and also does not have a companion star

- In the same blog comment as cited above[1], Randall explains that he chose the "sun exploding" scenario as a more clearly absurd example than those usually used:

…I realized that in the common examples used to illustrate this sort of error, like the cancer screening/drug test false positive ones, the correct result is surprising or unintuitive. So I came up with the sun-explosion example, to illustrate a case where naïve application of that significance test can give a result that’s obviously nonsense.

- "Bayesian" statistics is named for Thomas Bayes, who studied conditional probability — the likelihood that one event is true when given information about some other related event. From Wikipedia: "Bayesian interpretation expresses how a subjective degree of belief should rationally change to account for evidence".

- The "frequentist" says that 1/36 = 0.027. It's actually 0.02777…, which should round to 0.028.

- Using neutrino detectors to get an advance warning of a supernova is possible, and the Supernova Early Warning System does just this. The neutrinos arrive ahead of the photons, because they can escape from the core of the star before the supernova explosion reaches the mantle.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Comment by Randall Munroe to "I don’t like this cartoon", blog post by Andrew Gelman in Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science. Archived Jan 17 2013 by the Wayback Machine.

Discussion

I just sort of assumed he bet 50 dollars because if the sun had exploded, they'd be dead and therefore wouldn't need the machine. 108.162.237.16 07:05, 21 August 2020 (UTC)

Something should be added about the prior probability of the sun going nova, as that is the primary substantive point. "The neutrino detector is evidence that the Sun has exploded. It's showing an observation which is 35 times more likely to appear if the Sun has exploded than if it hasn't (likelihood ratio of 35:1). The Bayesian just doesn't think that's strong enough evidence to overcome the prior odds, i.e., after multiplying the prior odds by 35 they still aren't very high." - http://lesswrong.com/r/discussion/lw/fe5/xkcd_frequentist_vs_bayesians/ 209.65.52.92 23:51, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Note: taking that bet would be a mistake. If the Bayesian is right, you're out $50. If he's wrong, everyone is about to die and you'll never get to spend the winnings. Of course, this meta-analysis is itself a type of Bayesian thinking, so Dunning-Kruger Effect would apply. - Frankie (talk) 13:50, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- You don't think you could spend fifty bucks in eight minutes? ;-) (PS: wikipedia is probably a better link than lmgtfy: Dunning-Kruger effect) -- IronyChef (talk) 15:35, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Randall has referenced the Labyrinth guards before: xkcd 246:Labyrinth puzzle. Plus he has satirized p<0.05 in xkcd 882:Significant--Prooffreader (talk) 15:59, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

A bit of maths. Let event N be the sun going nova and event Y be the detector giving the answer "Yes". The detector has already given a positive answer so we want to compute P(N|Y). Applying the Bayes' theorem:

- P(N|Y) = P(Y|N) * P(N) / P(Y)

- P(Y|N) = 1

- P(N) = 0.0000....

- P(Y|N) * P(N) = 0.0000...

- P(Y) = p(Y|N)*P(N) + P(Y|-N)*P(-N)

- P(Y|-N) = 1/36

- P(-N) = 0.999999...

- P(Y) = 0 + 1/36 = 1/36

- P(N|Y) = 0 / (1/36) = 0

Quite likely it's not entirely correct. Lmpk (talk) 16:22, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Here's what I get for the application of Bayes' Theorem:

- P(N|Y) = P(Y|N) * P(N) / P(Y): = P(Y|N) * P(N) / [P(Y|N) * P(N) + P(Y|~N) * P(~N)]

- = 35/36 * P(N) / [35/36 * P(N) + 1/36 * (1 - P(N))]

- = 35 * P(N) / [35 * P(N) - P(N) + 1]

- < 35 * P(N)

- = 35 * (really small number)

So, if you believe it's extremely unlikely for the sun to go nova, then you should also believe it's unlikely a Yes answer is true.

I wouldn't say the comic is about election prediction models. It's about a long-standing dispute between two different schools of statisticians, a dispute that began before Nate Silver was born. It's possible that the recent media attention for Silver and his ilk inspired this subject, but it's the kind of geeky issue Randall would typically take on in other circumstances too. MGK (talk) 19:44, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

I agree - this is not directed at the US-presidential election. I also want to add, that Bayesian btatistics assumes that parameters of distributions (e.g. mean of gaussian) are also random variables. These random variables have prior distributions - in this case p(sun explodes). The Bayesian statistitian in this comic has access to this prior distribution and so has other estimates for an error of the neutrino detector. The knowlege of the prior distribution is somewhat considered a "black art" by other statisticians.

My personal interpretation of the "bet you $50 it hasn't" reply is in the case of the sun going nova, no one would be alive to ask the neutrino detector, the probability of the sun going nova is always 0. Paps

- Yes, you would be able to ask. While neutrinos move almost at speed of light, the plasma of the explosion is significally slower, 10% of speed of light tops. You will have more that hour to ask. (Note that technically, sun can't go nova, because nova is white dwarf with external source of hydrogen. It can (and will), however, go supernova, which I assume is what Randall means.) -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:19, 12 November 2012 (UTC)

- Our sun will not go supernova, as it has insufficient mass. It will slowly become hotter, rendering Earth uninhabitable in a few billion years. In about 5 billion years it will puff up into a red giant, swallowing the inner planets. After that, it will gradually blow off its lighter gasses, eventually leaving behind the core, a white dwarf. 50.0.38.245 01:58, 15 November 2012 (UTC)

- Please don't edit others' comments on talk pages; it's considered quite rude. On a talk page, discourse is meant to be conducted, by editors for the betterment of the article. For constructive discourse to occur, a person's words must be left in tact. The act of censorship hurts the common goal of betterment. Per Wikipedia, the authoritative source on how a wiki works best: "you should not edit or delete the comments of other editors without their permission." lcarsos_a (talk) 17:38, 13 November 2012 (UTC) Note: much of this conversation has been removed at the request of the authors.

I think the explanation is wrong or otherwise lacking in its explanation: The P-value is not the entire problem with the frequentist's viewpoint (or alternatively, the problem with the p-value hasn't been explained). The Frequentist has looked strictly at a two case scenario: Either the machine rolls 6-6 and is lying, or it doesn't rolls 6-6 and it is telling the truth. Therefore, there is a 35/36 probability (97.22%) that the machine is telling the truth and therefore the sun has exploded. The Bayesian is factoring in outside facts and information to improve the accuracy of the probability model. He says "Either the machine rolls 6-6 (a 1/36 probability, or 2.77%) or the sun has exploded (an aparently far less likely scenario). Given the comparison, the Bayesian believes it is MORE probable that the machine rolled 6-6 than the sun exploded, given the relative probabilities. If the latter is a 1 in a million chance (0.000001%), it is 2,777,777 times more likely that the machine rolled 6-6 than the sun exploded. To borrow a demonstration/explanation technique from the Monty Hall problem, if the machine told you a coin flip was heads, that would be 50% chance of occuring while a 2.7% chance of the machine lying, the probabilities would clearly suggest that the machine was more likely to be telling the truth. Whereas if the machine said that 100 coin flips had all come up heads (7.88x10^-31%). Is it more likely that 100 coin flips all came up heads or is it more likely the machine is lying? What about 1000 coin flips? or 1,000,000? I think the question is, whether one could assign a probability to the sun exploding. Also, I think they could have avoided the whole thing by asking the machine a second time and see what it answered. TheHYPO (talk) 19:09, 12 November 2012 (UTC)

Another source of explanation: http://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/43339/whats-wrong-with-xkcds-frequentists-vs-bayesians-comic --JakubNarebski (talk) 20:12, 12 November 2012 (UTC)

The P-value really has nothing to do with it. If I think that there is a 35/36 chance that the sun has exploded, then I should we willing to take any bet that the sun has exploded with better than 1:35 odds. For example, if someone bets me that the sun has exploded in which they will pay me $2 if the sun has exploded and I will pay them $35 if it hasn't, then based on my belief that the sun has exploded with 35/36 probability, then my expected value for this bet is 2*35/36 - 35 * 1/36 = 35/36 dollars and I will take this bet. Clearly I would also take a bet with 1:1 odds - my estimated expected value in the proposed bet in the comic would be 50*35/36 - 50 * 1/36 = $49 (approximately), and I would for sure take this bet. The Bayesian on the other hand has a much lower belief that the sun has exploded because he takes into account the prior probability of the sun exploding, so he would take the reverse side of the bet. The difference is that the Bayesian uses prior probabilities in computing his belief in an event, whereas frequentists do not believe that you can put prior probabilities on events in the real world. Also note that this comic has nothing to do with whether people would die if the sun went nova - the comic is titled "Frequentists vs Bayesians" and is about the difference between these two approaches. -- 171.64.68.120 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

The Labyrinth reference reminds me of an old Doctor Who episode (Pyramid of Mars), where the Doctor is also faced with a truthful and untruthful set of guards. Summarized here: http://tardis.wikia.com/wiki/Pyramids_of_Mars_(TV_story) Fermax (talk) 04:49, 14 November 2012 (UTC)

This is actually an example of the Base rate fallacy. --71.199.125.210 04:04, 19 November 2012 (UTC)

People have gone over this already, but just to be a bit more explicit: Let NOVA be the event that there was a nova, and let YES be the event that the detector responds "Yes" to the question "Did the sun go nova?" What we want is P(NOVA|YES)=P(YES|NOVA)*P(NOVA)/P(YES) Suppose P(NOVA)=p is the prior probability of a nova. Then P(YES|NOVA)=35/36, P(NOVA)=p, and P(YES)=p*35/36+(1-p)*1/36=1/36+34/36 So then P(NOVA|YES)=35p/(1+34p). If p is small, then P(NOVA|YES) is also small. In particular, the Bayesian statistician wins his bet at 1:1 odds if p<1/36, which is probably the case. If the Bayesian statistician wants 95% confidence that he'll win his bet, then he needs p<1/666. =P

It's cute to attempt to connect this to the U.S. presidential election, but it's far likelier that it's a reference to Enrico Fermi taking bets at the Trinity test site as to whether or not the first atomic bomb would cause a chain reaction that would ignite the entire atmosphere and destroy the planet. I'll bet you $50 it is. 71.229.88.206 21:29, 7 March 2013 (UTC)

I don't like the explanation at all. Some of the discussion posts give a good view on this. I'd like to share my thought about the last panel, though. The page reads as if the punch line is about the fact that you cannot spend the money if the sun was going to explode; but why does the bayesian propose this bet and not the frequentist - no reason for this. I think there is a better explanation for this panel: there are several proofs that bayesian probabilities result in "rational" behaviour: They state that if you act according to bayes' rule you cannot be cheated in betting. 108.162.254.179 17:11, 6 March 2014 (UTC)

The last panel may refer to Nate Sliver's view expressed in his book The Signal and the Noise that if one believes one's prediction to be true one should be confident to bet on it. --Troy0 (talk) 18:46, 6 July 2014 (UTC)

Please excuse my ignorance, but how is two sixes rolled on fair dice 31/32? (In the explanation: "the detector is telling the truth (31 in 32)") --Pudder (talk) 17:06, 9 December 2014 (UTC)

- Just a missreading, not stupid. The detector is telling the truth when you dont role 2 sixes. roling 2 sixes is 1/6 * 1/6 or 1/36. So not roling is 35 in 36, wait oops 36 not 32, thanks. 108.162.216.209 17:39, 9 December 2014 (UTC)

I have always thought that the suggested Bet is also a reference to the Dutch Book argument for judging and accounting for probabilities underlying Bayesian interpretations of probability theory. 141.101.98.100 22:11, 12 August 2015 (UTC)

The likelyhood of a solar explosion may be wrong. Since the detector I'd only used at night, the event is twice as likely to occur than listed. That said, there's a 50% chance of the event never being detected, so I'm not sure. Any one more knowledgeable than I care to comment? Mikemk (talk) 06:47, 5 April 2016 (UTC)

Huh. I thought that the last panel was pragmatism: "If the sun goes nova, $50 doesn't matter; I'll be dead. If the sun hasn't, I get $50!"

This comic hurts my head. 173.245.54.7 21:44, 12 August 2019 (UTC)

It is my feeling that sloppy or machiavellian academics have come to use the term "Bayesian" to mean something more like "we adjusted it to what we felt was most reasonable", which introduces so much bias that it actually leaves one unable to determine the scientific validity of the results. I was reading a publication, today, that made me think of that and look up this comic. —Kazvorpal (talk) 21:57, 11 November 2019 (UTC)

Is there a statistical angle I'm missing to the final part of the mouseover text 'did your brain fall out? [roll] yes...' Or is is purely linguistic between literal and figurative i.e. if his brain has fallen out as in he has made a careless error, then that's true. If it's literally did his brain fall out, is the 'yes' the 97% chance that it's talking about his mistake, or the ~3% chance that it's lying about the literal truth? 172.69.69.244 14:46, 3 December 2019 (UTC)

As per Sagan, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence". 108.162.229.54 10:42, 12 October 2020 (UTC)

When he Bayesian says "Bet you $50 it hasn't.", he is saying that he will probably win the bet. However, he isn't saying he knows whether the sun has exploded or whether the detector is lying. What he is saying is roughly equivalent to "If we are playing Texas Holdem and I have a royal flush while you have nothing showing, I am probably going to win and might as well bet what I can.

If the eventist says "Detector! What would the Bayesian statistician say if I asked him whether I would say the sun had exploded", the Bayesian doesn't know what the detector would say. (I am changing the wording slightly, but it doesn't make sense to me as stated.) Therefore, the Bayesian can't give an answer. The Bayesian's answer would therefore be "I am a neutrino detector (answers are sometimes true and sometimes false), not a labyrinth guard (answers are always true or always false)". He then predicts that the Bayesian would say "Seriously, did your brain fall out?" After somebody hits the button, the detector answers truthfully (the likeliest option), and gives his opinion "YES". BradleyRoss (talk) 01:26, 23 February 2023 (UTC)

With regard to Bayesian having multiple meanings, this is probably similar to there being a Turing test, a Turing machine, and Turing Complete. BradleyRoss (talk) 01:32, 23 February 2023 (UTC)

No-one has discussed how to properly apply frequentists statistics to the problem. 1: Rerun the test several dozen times. 2: Find the 95% confidence interval of the generated data (A Poisson distribution is most appropriate for the modeling of event frequency). 3: If the 95% confidence interval includes the value of 1/36 then it supports the null hypothesis that there is no correlation is suggested between the sun and the positive detector results. Bayesian and Frequentist Statistics should yield the same result if handled correctly, because they are basically algebraic rearrangements of each other. --172.71.154.215 21:33, 24 March 2023 (UTC)

!['Detector! What would the Bayesian statistician say if I asked him whether the--' [roll] 'I AM A NEUTRINO DETECTOR, NOT A LABYRINTH GUARD. SERIOUSLY, DID YOUR BRAIN FALL OUT?' [roll] '... yes.'](/wiki/images/7/78/frequentists_vs_bayesians.png)