Difference between revisions of "1455: Trolley Problem"

(Grammar.) |

Whalepilot (talk | contribs) (→Trivia: more comics mentioning the trolley problem) |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

==Trivia== | ==Trivia== | ||

| − | *Three years later two comics were released with about one month between them where the Trolley problem was mentioned. In [[1925: Self-Driving Car Milestones]] it is in the last ''milestone'' on the list and a month later, in [[1938: Meltdown and Spectre]], it is used as a metaphor for the way some computer programs work. | + | *Three years later two comics were released with about one month between them where the Trolley problem was mentioned. In [[1925: Self-Driving Car Milestones]] it is in the last ''milestone'' on the list and a month later, in [[1938: Meltdown and Spectre]], it is used as a metaphor for the way some computer programs work. It would subsequently come up again in [[2635: Superintelligent AIs]], [[2702: What If 2 Gift Guide]], and [[2818: Circuit Symbols]]. |

{{comic discussion}} | {{comic discussion}} | ||

Revision as of 04:21, 22 August 2023

| Trolley Problem |

Title text: For $5 I promise not to orchestrate this situation, and for $25 I promise not to take further advantage of this ability to create incentives. |

Explanation

The trolley problem is a thought experiment often posed in philosophy to explore moral questions, with applications in cognitive science and neuroethics. The general version is that an out of control trolley (or train) is heading towards 5 people on the track who can't get out of the way. On an alternative branch of the track is 1 person who can't get out of the way. The trolley can be diverted by using a lever, with the consequence of saving the 5 people but killing the 1 person.

The choice is between a deliberate action that will directly kill one person, or allowing events to unfold naturally, resulting in five deaths. The question posed is whether or not it is morally right to pull the lever. The moral question is not as simple as it may first appear.

This results of this test report that around 86% of respondents choose the utilitarian option of diverting the trolley.

There are, however, several alternative formulations of the same basic dilemma. One such scenario allows you to stop the trolley by deliberately pushing "a very fat man" into its path, killing the man but saving the other five people. Another scenario involves selecting a healthy young and innocent person to die, in order to save five others going through organ donation. In both of these examples the basic dilemma is the same. However, most people reject the utilitarian option in these cases.

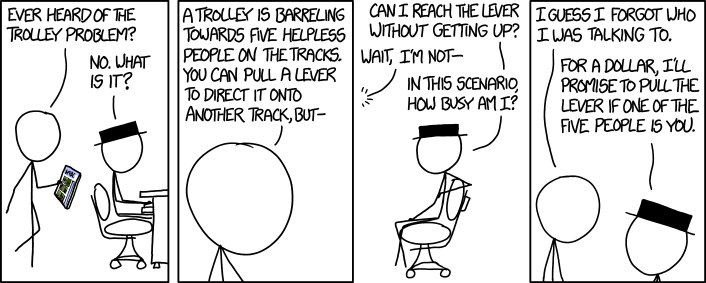

After discovering a variation on this problem posed in a strip of the Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal webcomic (which can be seen on the tablet he is carrying), Cueball, Black Hat's roommate, presents it to Black Hat. Before Cueball can finish explaining the problem, most notably leaving out the disadvantage to flipping the lever where it would kill one person, Black Hat questions whether he would need to get up to reach the lever and how much it would interrupt his other activities. As usual, he cares nothing at all about what happens to other people. This response is linked to another theory in philosophy, that of self interest or egoism or Objectivism, in which a person will choose the action with the most benefit for them personally.

Black Hat then poses an offer: he promises to divert the trolley if Cueball is one of the five endangered people, provided that Cueball pays him $1 now. Again Black Hat is twisting the situation to his own benefit, in this case monetary. In the case of self-interest, the $1 could be the price at which Black Hat values his time and effort, below which he feels there is no benefit to himself in pulling the lever. Cueball decides that there is no point posing the problem to someone like Black Hat and gives up. This further shows that it is challenging for people with different ethical frameworks to function together without a common understanding, either mutually or with one side using that understanding to motivate a mutually agreeable or horrible solution.

The title text follows this up by continuing Black Hat's offers. For $5 he will not deliberately arrange this situation and for $25 he will quit looking for further incentives. These attempts to exploit the thought exercise for personal gain further demonstrate Black Hat's cynical amorality.

Black Hat's offer makes Cueball himself the subject of the trolley problem: Cueball now has a choice of expending $1 to save 5 people while sacrificing one person, or $5 to save all 6 people. Of course, he could dismiss the offer as a joke, if not for the fact that the person making it, which, as we know from other comics, is very much capable of such exploits.

Transcript

- Cueball: Ever heard of the trolley problem?

- Black hat: No. What is it?

- Cueball: A trolley is barreling towards five helpless people on the tracks. You can pull a lever to direct it onto another track, but-

- Black hat: Can I reach the lever without getting up?

- Cueball: Wait, I'm not-

- Black hat: In this scenario, how busy am I?

- Cueball: I guess I forgot who I was talking to.

- Black hat: For a dollar, I'll promise to pull the lever if one of the five people is you.

Trivia

- Three years later two comics were released with about one month between them where the Trolley problem was mentioned. In 1925: Self-Driving Car Milestones it is in the last milestone on the list and a month later, in 1938: Meltdown and Spectre, it is used as a metaphor for the way some computer programs work. It would subsequently come up again in 2635: Superintelligent AIs, 2702: What If 2 Gift Guide, and 2818: Circuit Symbols.

Discussion

True gamers realise they can start MULTI DRACK DRIFTING and derail the train by fiddling with the switch.162.158.50.240 07:30, 30 March 2020 (UTC) I think Randall missed a trick here.. He should have had Black Hat offer to leave the lever (killing the 5) if Cueball was the 1 person on the other track, for $1 of course. That way Cueball is put in a situation of moral contradiction: The utilitarian in him says save the 5 (sacrifice self), self interest says save yourself (thereby killing 5). --Pudder (talk) 09:24, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Randall had to make a choice between your scenario and Black Hat interrupting Cueball to emphasise BH's lack of care for the people on the track. As he chose the latter, BH didn't know there was a person on the second track, so couldn't have offered your scenario. -- Notso (talk) 11:05, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Good point, I hadn't noticed that BH was never aware of the single person. That makes BH an even less moral person than I'd realised! As far as he knows, he could save 5 lives with no consequences, but that means standing up.... --Pudder (talk) 12:00, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think Randall made the morally correct choice there, don't you? -- Brettpeirce (talk) 12:38, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Thats the thing with morals, something is only 'morally correct' if I subscribe to your moral viewpoint. While not such a popular view, some would argue that intervening to switch the track (thus causing the 1 worker to die) is morally wrong (because of your action you have changed the course of events, or some other reason). While most would agree that it is morally wrong to kill a human, as you start changing the circumstances, it become difficult to stick to hard and fast rules. What about abortion of a foetus, abortion where a life-limiting condition is detected, use of condoms, the death penalty, euthanasia? I would really recommend anyone to run through some of the Philosophy Experiments, it certainly made me examine my own morals, which previously I thought were well defined and logical. --Pudder (talk) 13:23, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- "some would argue that intervening to switch the track (thus causing the 1 worker to die) is morally wrong (because of your action you have changed the course of events"

- If you base morality on what choices are made, rather than what actions are taken, then failing to intervene, choosing not to take action, would be morally wrong. Basing morals on actions suggests someone could stand by and always do nothing and remain moral. A position I don't think anyone could seriously defend. But you're absolutely right that "morals" are never well defined or logical. An example can always be found to put someone's strong moral stance in an immoral position. --Equinox 199.27.128.117 17:41, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- The majority of people will make a distinction between killing someone and letting someone die, even if that distinction isn't something they are conscious of. Of course the end result is the same, whether it is classed as killing or letting die. For those whose morals are guided by christianity for example, the ten commandments specifically states 'Thou shalt not kill', and your action of pulling the lever could be seen as killing the 1 person, whereas by not acting, or choosing not to act, you are 'merely' letting 5 people die. --Pudder (talk) 21:03, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Actually, the Bible says, "Thou shalt not commit murder." Hebrew draws the same distinction between "murder" and "killing" as modern law--murder is intentional and illegal killing. It's perfectly OK, for example, to kill hundreds of Philistines and mutilate their genitals if you want to marry a hot princess. (Note: that's an actual Bible story, from early in the life of David.) Nitpicking (talk) 04:39, 21 December 2021 (UTC)

- Folks who make some kind of moral distinction between choosing to kill someone and choosing to let someone die are just trying to avoid responsibility for their actions. It's a self-righteous and self-serving. Masking that by claiming some religeous basis (God said "Thou shall not kill" so I'm, ahem, just following orders.) doesn't change that.

- I'm not in any way suggesting it wouldn't be a wrenching and difficult decision to have to make. But someone claiming they can choose not to decide who lives and who dies (while in fact they are thereby actually making that decision) and therefore not have any responsibility for what happens as a consequence is simply lying.

- To perhaps more clearly show how choosing to "let" multiple people die isn't really OK morally, make it a large number of people. What if the train is headed toward 500 people? Most folks who might be OK with "letting" 5 die would balk well before the exchange rate got near 500:1. I realize this kind of contemplating "where do you draw the line" is what the trolley problem is designed to produce. Thanks for the discussion.--Equinox 199.27.128.117 17:39, 4 December 2014 (UTC)

- Very interesting discussion, all. A few points. First, some eastern philosophies ascribe moral culpability to one who intervenes; if, indeed, one intervenes to save the 5 by throwing the switch, one is responsible for the death of the other (and you also responsible for the subsequent actions of the 5 you saved.) Yes, this flies in the face of western values, but it is no less valid (echoing the "if you agree with my morals" sentiment.) Not right. Not wrong. Just different. Secondly, if it is morally wrong to sit by and do nothing, thus letting the 5 die, there is a bit of hypocracy there. By that reasoning, failing to give every dollar you have to feed the hungry (that would otherwise die for lack of food) would be equivalent of not throwing the switch. That is to say: for each dollar you have, you could do nothing and let 4 people die, or you could donate it and save them. That's not intended to be a screed for any viewpoint or dogma, only an observation that morals and values tend to shift with circumstances... Anyway, excellent stuff. -- IronyChef (talk) 06:44, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

- Its so refreshing to have this discussion with people who actually consider the variety of opposing viewpoints, rather than going "This is my view, and everything else is wrong." As far as changing the ratio of people on the tracks, my guess is that as the number of people saved goes up, the more people would feel it was morally right to change the lever. Along the lines of 70% of people would switch at 5:1, 85% at 50:1, 95% at 500:1 (Just my guesses). I would also guess that there are a certain percentage of people would not switch even with 5,000,000 on the first track. These people have their moral rule set in stone, even where others may not understand it. If you bring the ratio in the other direction, I wonder what would happen at 1:1? How many people would actively change the person who was killed? I would guess that people may well start using the word 'fate' to explain their decision... --Pudder (talk) 08:34, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

- The curve would probably not be so perfectly asymptotic, as other influences (or releases of moral pressure) come to play. "The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic." Of course, the choice of 5 million vs 1 via runaway track-based vehicle is going to be... contrived at best... perhaps the closest 'likely' equivalent would be an Armageddon/Deep Impact-type situation and influenced (in a typically cinematic way) by your emotional attachment to the one person your actions (setting off the "save the planet" mechanism) would end up killing instead. At some point, "everyone on Earth vs the one person might actually care about" might turn out to be a no-brainer in the (wrong?) direction. Perhaps sending two people (or a close-knit team) with no Earthly attachments on the potentially suicidal mission isn't ideal. ;) 141.101.98.247 16:51, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

- Its so refreshing to have this discussion with people who actually consider the variety of opposing viewpoints, rather than going "This is my view, and everything else is wrong." As far as changing the ratio of people on the tracks, my guess is that as the number of people saved goes up, the more people would feel it was morally right to change the lever. Along the lines of 70% of people would switch at 5:1, 85% at 50:1, 95% at 500:1 (Just my guesses). I would also guess that there are a certain percentage of people would not switch even with 5,000,000 on the first track. These people have their moral rule set in stone, even where others may not understand it. If you bring the ratio in the other direction, I wonder what would happen at 1:1? How many people would actively change the person who was killed? I would guess that people may well start using the word 'fate' to explain their decision... --Pudder (talk) 08:34, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

- Very interesting discussion, all. A few points. First, some eastern philosophies ascribe moral culpability to one who intervenes; if, indeed, one intervenes to save the 5 by throwing the switch, one is responsible for the death of the other (and you also responsible for the subsequent actions of the 5 you saved.) Yes, this flies in the face of western values, but it is no less valid (echoing the "if you agree with my morals" sentiment.) Not right. Not wrong. Just different. Secondly, if it is morally wrong to sit by and do nothing, thus letting the 5 die, there is a bit of hypocracy there. By that reasoning, failing to give every dollar you have to feed the hungry (that would otherwise die for lack of food) would be equivalent of not throwing the switch. That is to say: for each dollar you have, you could do nothing and let 4 people die, or you could donate it and save them. That's not intended to be a screed for any viewpoint or dogma, only an observation that morals and values tend to shift with circumstances... Anyway, excellent stuff. -- IronyChef (talk) 06:44, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

- The majority of people will make a distinction between killing someone and letting someone die, even if that distinction isn't something they are conscious of. Of course the end result is the same, whether it is classed as killing or letting die. For those whose morals are guided by christianity for example, the ten commandments specifically states 'Thou shalt not kill', and your action of pulling the lever could be seen as killing the 1 person, whereas by not acting, or choosing not to act, you are 'merely' letting 5 people die. --Pudder (talk) 21:03, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Thats the thing with morals, something is only 'morally correct' if I subscribe to your moral viewpoint. While not such a popular view, some would argue that intervening to switch the track (thus causing the 1 worker to die) is morally wrong (because of your action you have changed the course of events, or some other reason). While most would agree that it is morally wrong to kill a human, as you start changing the circumstances, it become difficult to stick to hard and fast rules. What about abortion of a foetus, abortion where a life-limiting condition is detected, use of condoms, the death penalty, euthanasia? I would really recommend anyone to run through some of the Philosophy Experiments, it certainly made me examine my own morals, which previously I thought were well defined and logical. --Pudder (talk) 13:23, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

Black Hat first sells his hypothetical decision for $1, which can be seen as a cheap bargain for one's life; but how probable is this concrete situation with these exact persons to come true, except we are speaking of Black Hat here. $5 still is for a hypothetical, but more probable scenario given Black Hat's attitude; agreeing to pay would make Cueball open for further blackmailing in general and so be imprudent, but even for that counter-argument Black Hat has an even more expensive solution. Black Hat goes more and more meta and counters arguments bringing the concrete decision from hypothesis to reality and earning money on the way. Sebastian --108.162.231.68 10:13, 3 December 2014 (UTC) Pudder

Or one can treat this like Captain Kirk did with the infamous "Kobayashi Maru" problem and cheat, and say that they would throw the lever after the lead wheels have cleared the switch. This would divert the trailing wheels onto the other track which would cause the trolley to derail and thus save all six.108.162.216.94 13:16, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- And kill everyone on board! Its easy to cheat, and construct ways to avoid the hypothetical situation, or reasons why it could never happen in the first place. To me its more interesting to examine and challenge the thought process involved in making a decision where the answer isn't necessarily 'correct'. --Pudder (talk) 13:27, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Nowhere does it say there are people on the trolley. You are assuming that there are. I am assuming the opposite — that it is a runaway and no one is aboard; otherwise someone would be able to apply the brakes.108.162.216.94 15:06, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- My response was an off the cuff joke, it doesn't matter whether there are people on board, whether they would survive, whether they could pull the brakes on, if the brakes have failed, whether you could fire an orange portal in front of the 5 people and a blue one after them, etc etc etc. The importants part is the second half of my statement, that its easy to cheat, and construct ways to avoid the hypothetical situation, or reasons why it could never happen in the first place. Once you accept the hypothetical limits of the situation, that is where the interesting philosophical questions lie. --Pudder (talk) 15:30, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- I'd like to play devil's advocate for those that go for the third option. I agree with your points that the problem must be treated as it is, but on the other hand it's very unlikely we are going to face such an hypothetical situation in real life. The fact that, in real life, there's could be a myriad ways we could take the third option makes people prefer to think about it, because it's more practical, than to think on the hypothetical situation, because it has no use in real life. I'm not implying that it's pointless to discuss the hypothetical situation, but I'm just showing that thinking on third options has more value than it seems. 188.114.99.189 00:09, 3 December 2015 (UTC)

- My response was an off the cuff joke, it doesn't matter whether there are people on board, whether they would survive, whether they could pull the brakes on, if the brakes have failed, whether you could fire an orange portal in front of the 5 people and a blue one after them, etc etc etc. The importants part is the second half of my statement, that its easy to cheat, and construct ways to avoid the hypothetical situation, or reasons why it could never happen in the first place. Once you accept the hypothetical limits of the situation, that is where the interesting philosophical questions lie. --Pudder (talk) 15:30, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- The correct answer is to have a moral trolley company that trains its workers to OSHA rules; thus the correct answer would be to throw the lever to head towards the worker, confident that the worker has been trained to listen to the "singing of the rails" indicating an approaching vehicle and will jump out of the way. Seebert (talk) 13:49, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- If the trolley is a runaway trolley, then it's a good chance that all on board (if anyone) would die anyway, so may as well save all six people on the track. --108.162.217.131 14:46, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- Nowhere does it say there are people on the trolley. You are assuming that there are. I am assuming the opposite — that it is a runaway and no one is aboard; otherwise someone would be able to apply the brakes.108.162.216.94 15:06, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

The explanation is missing that Black Hat doesn't offer to press the lever for $1. He offers to promise to press the lever for $1. Hsdgsgh (talk) 13:57, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

It depends - are any/all of those five people Hitler? 108.162.215.48 16:54, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

The tiered levels appear similar to kickstarter campaigns. 108.162.216.91

The trolley problem continues: The trolley is under control, but heading towards a bend. If the driver brakes now, then the five people hidden round the corner will survive. You could certainly make the driver brake by pushing someone onto the track. If you would divert the trolley in the original scenario, would you also push a random stranger into the path of an oncoming train, and if not, why not. Does the more visceral act of pushing someone onto a track make this morally different? 141.101.98.201 20:57, 3 December 2014 (UTC)

- This is how I heard it back around 10 years ago - Out of control trolley heading towards 5 people who would die, but you could save them if you pushed a person onto the track thereby derailing the trolley (and killing the pushee) - but when a person answered "Why yes, I would push the person", you would reply with "But why didn't you choose to sacrifice yourself?" And then the real conversation would commence. Zang

- Definately another route to explore with some interesting moral questions. In the versions I've seen, the man is specifically identified as a fat man, with the reasoning being that only a fat man on the tracks would stop the trolley. (Ignoring the fact that the respondent may be similiarly fat). Basically it tries to replicate the original scenario but with the physical action of pushing someone onto the tracks. --Pudder (talk) 09:21, 9 December 2014 (UTC)

- The statistics show that far fewer people will push the person onto the track than would change the lever. As you say, its far more visceral and personal to push someone than to flick a switch. -- Pudder (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- (Without checking that link, which probably contains the reasons why what follows is incorrect), my first thought is that if I'm in a position to push a person onto a track, I'm probably close enough to myself run onto (or at least close enough to) the track, waving my arms to alert the driver, perhaps at my own risk. Also, I was on a train that ran into a (small, recently felled) tree on the line, the other day. Not relevent, probably, but an interesting synchronicity to me. 141.101.98.247 16:51, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

Depending on the speed of the trolley and the steepness of the turn after the points, the trolley could derail anyway, saving the lives of all six but bringing a hastened demise to anyone on board. 108.162.250.204 02:06, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

"Black Hat may also be attempting to solve such interruptions for the bargain price of a $1, by claiming he would pull the lever to save Cueball when really he just wants some future distractions to be in danger - namely Cueball". - I don't understand this line at all. Is anyone able to clarify? --Pudder (talk) 09:43, 5 December 2014 (UTC)

The comic strip "Cow and Boy" once posed this question, and I cannot find fault with Cow's answer - Cow stated that no, you should not pull the lever, because "why punish the only person smart enough to avoid an oncoming train?" --Andrew Williams, 6 December 2014