Difference between revisions of "675: Revolutionary"

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

| − | The comic contrasts brilliant revolutionary scientific thought with the simplistic arrogance of assuming one understands the current scientific theory enough to correct it, known under the {{w|Dunning Kruger effect}}. The character with the goatee has a degree in {{w|philosophy}}, and perhaps has certain ideas of his own about how the world should fundamentally be described by physics. He has studied Einstein's {{w|theory of special relativity}} | + | The comic contrasts brilliant revolutionary scientific thought with the simplistic arrogance of assuming one understands the current scientific theory enough to correct it, known under the {{w|Dunning Kruger effect}}. The character with the goatee has a degree in {{w|philosophy}}, and perhaps has certain ideas of his own about how the world should fundamentally be described by physics. He has studied Einstein's {{w|theory of special relativity}} about an hour and thinks he has found a flaw. When confronted about this, he considers the objection as based in {{w|dogma}}, and remains so confident that he wants to email the "president of physics". His ignorance of the field is emphasized by thinking that the entire field of physics has a president - although certain important organizations such as the {{w|American Physical Society}} do have presidents. |

[[Cueball]] concedes that it is possible for such a revolutionary idea to come from a relative outsider. One example is {{w|Albert Einstein}}'s own formulation of {{w|special relativity}}, which came while he was working at a patent office in Switzerland, although he did already have a Ph.D in physics. A {{w|thought experiment}} considers some hypothesis, theory, or principle for the purpose of thinking through its consequences. | [[Cueball]] concedes that it is possible for such a revolutionary idea to come from a relative outsider. One example is {{w|Albert Einstein}}'s own formulation of {{w|special relativity}}, which came while he was working at a patent office in Switzerland, although he did already have a Ph.D in physics. A {{w|thought experiment}} considers some hypothesis, theory, or principle for the purpose of thinking through its consequences. | ||

Revision as of 01:02, 21 November 2024

| Revolutionary |

Title text: I mean, what's more likely -- that I have uncovered fundamental flaws in this field that no one in it has ever thought about, or that I need to read a little more? Hint: it's the one that involves less work. |

Explanation

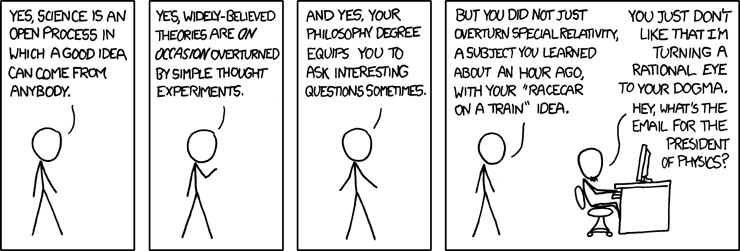

The comic contrasts brilliant revolutionary scientific thought with the simplistic arrogance of assuming one understands the current scientific theory enough to correct it, known under the Dunning Kruger effect. The character with the goatee has a degree in philosophy, and perhaps has certain ideas of his own about how the world should fundamentally be described by physics. He has studied Einstein's theory of special relativity about an hour and thinks he has found a flaw. When confronted about this, he considers the objection as based in dogma, and remains so confident that he wants to email the "president of physics". His ignorance of the field is emphasized by thinking that the entire field of physics has a president - although certain important organizations such as the American Physical Society do have presidents.

Cueball concedes that it is possible for such a revolutionary idea to come from a relative outsider. One example is Albert Einstein's own formulation of special relativity, which came while he was working at a patent office in Switzerland, although he did already have a Ph.D in physics. A thought experiment considers some hypothesis, theory, or principle for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

The "racecar on a train" idea alludes to thought experiments involving frames of reference, which are important in relativity. Special relativity was famously established using some thought experiments about moving objects. However, some searchers elaborated more complicated thought experiments and claimed they had proven relativity was self-contradictory. Examples include twin paradox (both of the twins are younger than the other, until you stop assuming acceleration phases can be neglected) or ladder paradox (ladder is both smaller and larger than the garage, until you consider seriously the problems with defining simultaneity for remote locations in relativity). Apparently the philosopher complicated Einstein's train thought experiment by adding a racecar, and found contradictions which prove special relativity is inconsistent. However, most likely scenario is that the "racecar on a train" is too complicated for goatee man to find correct conclusions.

A too complex case may be impossible to prove consistent with relativity using intuition alone: complete solving involves calculation using Lorentz transformations.

The title text is posing a question about the likelihood of two scenarios (possibly to the person with the philosophy degree):

- That decades of work by numerous physicists is fundamentally incorrect, and I found the flaw immediately

- That I need to read a little more

This might be a self-referential title text as this question could be considered a simple thought experiment. The philosopher should be able to overturn his theory using this simple thought experiment which reflects the second panel. While his theory is not widely believed the joke is that the philosopher could overturn his first thought experiment (racecar on train) with this thought experiment.

Randall hints that believing you have found fundamental flaws in a theory is much easier than doing more research on it. This is possibly a statement about using Occam's Razor in arguments, which says the simpler answer is the more likely one, which is commonly brought up in philosophy. Usually, when someone with little understanding of the subject thinks that they have found a flaw, it takes only a little bit more reading to discover that the flaw is in fact completely explained already.

Transcript

- Cueball: Yes, science is an open process in which a good idea can come from anybody.

- Cueball: Yes, widely-believed theories are on occasion overturned by simple thought experiments.

- Cueball: And yes, your philosophy degree equips you to ask interesting questions sometimes.

- [Cueball is talking to a philosopher with a goatee, who is sitting at a computer.]

- Cueball: But you did not just overturn special relativity, a subject you learned about an hour ago, with your "racecar on a train" idea.

- Philosopher: You just don't like that I'm turning a rational eye to your dogma. Hey, what's the email for the president of physics?

Discussion

Looks like this guy doesn't know about Lorentz contraction and time dilation. That or he's so confident about his idea that he hasn't bothered to look further into the subject. --ParadoX (talk) 09:24, 10 December 2013 (UTC)

Looks like this guy

- Had we forgotten George Dantzig? The world would have made much more progress had it not been propaganda like this discouraging people from thinking.

They both look the same to me. Which one do you mean? I used Google News BEFORE it was clickbait (talk) 22:06, 27 January 2015 (UTC)

I guess that the mouseover text refer to the Occam's razor, a favourite tool of many philosophers. --Barfolomio (talk) 14:07, 21 August 2014 (UTC)

- Welcome Barfolomio, but I think the Occam's razor principle wasn't in mind of Randall when he wrote this comic. But it's a nice find and maybe it should be mentioned. Nevertheless the title text explain is wrong, reading all the math and physics books is much harder then just inventing a "racecar on a train" theory as a philosopher. --Dgbrt (talk) 21:09, 21 August 2014 (UTC)

- The title text specifically compares two things.

- That I have uncovered fundamental flaws in this field that no one in it has ever thought about (implying that decades of work by numerous physicists is wrong)

- That I need to read a little more.

- The actual invention of the idea doesn't come into it. It takes minimal effort to invent an incorrect theory.

- In the vast majority of these cases, reading a little bit more into the subject results in finding out that the flaw you think have found is in fact already explained.

- As an example, lets say a high school student happens to do sqrt(5-6), he thinks he has uncovered a sum which has no answer. His calculator tells him 'Error'. In fact, with a little more reading, he would discover that mathematicians have a whole area devoted to this type of maths, namely imaginary numbers. --Pudder (talk) 15:43, 9 September 2014 (UTC)

- The title text specifically compares two things.

The relativity sections of physics forums like www.physicsforums.com, despite having FAQs and pinned posts with explanations, are often full with new threads claiming that relativity is obviously wrong because of "insert simple example here that uses normal velocity addition instead of Lorentz transforms", maybe Randall is a participant in such a forum? 141.101.93.206 08:32, 6 November 2014 (UTC)

- None the less the fact remains that there are at least three completely different explanations known. Or at least there were, the last time I spent a couple of hours on the subject (one hell of a while back.)

- Once I got to the fact that there were a lot of alternative values for time -let's face it, that is what it is all about in the first place... I just lost interest.

I used Google News BEFORE it was clickbait (talk) 22:06, 27 January 2015 (UTC)

Dgbrt, I have reverted your edit which removed the example using imaginary numbers. I understand that the example uses imaginary numbers which are not referenced in the comic, however rather than removing a paragraph which gives a succinct example of the comics content (and points out that it is only an example), it would be far more useful to change the paragraph to reference special relativity instead of imaginary numbers. There are two reasons I didn't do this when I wrote the paragraph: Firstly, I don't understand special relativity in enough detail to give an example where a 'flaw' is easily explained, and secondly most readers probably don't either. Because of this I used imaginary numbers which I would think a larger proportion of people have come across in some form before. --Pudder (talk) 10:15, 7 November 2014 (UTC)

- I removed this paragraph because "sqrt(5-6)" or "imaginary numbers" do not help to explain the comics content — less than 5% will understand only that phrases. We can't explain special relativity — using "imaginary numbers" — to a common reader. BUT we can explain how or why some people NOT understanding Einstein still trying to invent better solutions... without any knowledge of the real matter. I did not remove it again, so it's up to you to give a better explain.--Dgbrt (talk) 22:27, 7 November 2014 (UTC)

- I disagree that it doesn't help the explanation. It gives a fairly simple example of somebody who thinks they have found a flaw, but where it would take minimal extra reading to realise its actually not a flaw (which is the whole concept of this comic). I would argue that substantially more than 5% of readers will have come across imaginary numbers, if they haven't then the wiki link is there for them to look them up. The fact that it refers to imaginary numbers is actually not even particularly relevant, only that there is a field of mathematics to explain the sqrt(5-6) "flaw". Maybe the explanation could be improved by changing the example to relate to special relativity, but as I said before I'm not qualified to write that. --Pudder (talk) 09:21, 10 November 2014 (UTC)

Less work, says the title text. But - less work for WHO? See, actually correcting a widely accepted theory (or replacing it) takes a *lot* of work. Lots of textbooks to be rewritten. Lots of courses to be updated. Errata on material too valuable to discard completely. Lots of people to be informed - this is after the conferences and papers that establish the overturning of the existing widely accepted theory. Which in themselves are usually going to take a few years. It's just that there is a chance that the person uncovering the problem may be able to escape all that work ... although this is only going to happen for someone outside the field; for someone inside, they'll be writing papers and textbooks and doing the work, and they may expect to build considerable prestige as a result. Rachel 108.162.222.38 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- You know, I had always read the title text as if overturning a rigorously supported and integral theory was more work but then I realized it's from a layman's perspective. Lackadaisical (talk) 12:58, 27 July 2016 (UTC)