1431: Marriage

| Marriage |

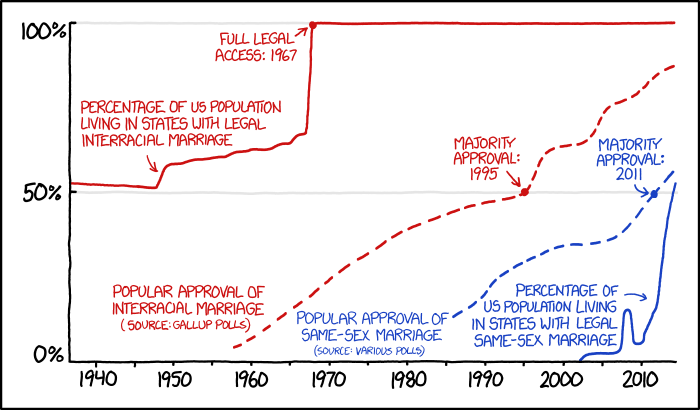

Title text: People often say that same-sex marriage now is like interracial marriage in the 60s. But in terms of public opinion, same-sex marriage now is like interracial marriage in the 90s, when it had already been legal nationwide for 30 years. |

Explanation

The comic notes a curious inversion between the timing of legal and popular opinion trends for interracial marriage vs. same-sex marriage. In the 11 years between Massachusetts first legalized same-sex marriage and the comic's publication, at no point had there been more people living in states where it's legal than there are people who support its legality. This stands in stark contrast to interracial marriage, which was legal for the majority of the population for over 50 years, and for the whole country for 28 years, before it was approved of by the majority.

Note that poll questions are slightly different: "Do you approve of interracial marriage?" vs "Do you think same-sex marriage should be legal?" It could be argued that fewer people would approve of these marriages than would support legalizing them, which may explain part of the discrepancy. But there are more factors at work, the effects and relative importance of which are not clear.

Recent developments

Two days before this comic came out, the United States Supreme Court declined to hear appeals to decisions that had legalized same-sex marriage in five states. The court's refusal to hear the appeals was widely considered a surprise, and had the immediate effect of pushing the percentage of people living in states where such marriages are legal past 50%. The decision has also led to considerable speculation that there will be a surge of similar decisions applying to other states, especially to the six states that are in the same appeals circuits as the previous five, and to the three in the same circuit as Idaho and Nevada, where same-sex marriage bans were struck down a day after the Supreme Court's decision (although the decision in Idaho and Nevada has yet to take effect).

On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States of America ruled in a 5-4 decision that access to same-sex marriage was a right protected by the Constitution, thus raising the percentage of states with legal same-sex marriage to 100%.

Interracial marriage trend line annotated

Legal controls concerning interracial marriage in the US (known since 1863 as miscegenation) have been significantly harder to track as a single statistic, due in part to the fact that such controls existed in several of the American British colonies before the United States formed, and complicated somewhat by the changes in territory claimed by and fluctuations in overall population (and methods of counting the population) of the United States over that time period. Depicting this as a simple percentage of US population over these earlier times would be far less meaningful outside of the context of these other fluctuations.

- Start of line

- Prior to ca. 1940 and continuing to 1948: Since the establishment of the United States, most states have had anti-miscegenation legislation in one form or another. Only nine states (Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, Hawaii) and the District of Columbia never enacted such legislation. Earlier repeal dates range from 1780 in Pennsylvania to 1887 in Ohio, though none were repealed between 1887 and 1948.

- First rise

- October 1948: Supreme Court of California overturns the state anti-miscegenation law in Perez v. Sharp.

- General upward trend

- 1951–1967: (in order of repeal by year) 13 states repeal anti-miscegenation laws prior to rulings at the federal level of government, largely encouraged by comparisons to similar laws promoted by opponents in World War II and other civil rights movements and victories.

- Last spike

- 12 June 1967: The U.S. Supreme Court rules in Loving v. Virginia that the 16 remaining state-level anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional, rendering such laws thereafter ineffective.

Same-sex marriage trend line explained

- Start of line

- 2003: Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court rules in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that the Massachusetts Constitution does not allow the denial of marriage licenses to same-sex couples.

- First rise

- May–October 2008: The supreme courts of California and Connecticut make similar decisions based on their states' constitutions.

- Drop

- November 2008: The voters of California overturn their supreme court's decision by constitutional amendment on Proposition 8. California is the most populous state in the Union, hence the large size of the drop here.

- Second rise

- 2009–2010: Iowa, Vermont, New Hampshire, and the District of Columbia legalize same-sex marriage, the first by state supreme court decision, and the latter three by legislative action.

- First acceleration

- 2011–2012: New York legalizes same-sex marriage by legislative action. Washington State, Maine, and Maryland do so by voter referendum.

- Second acceleration

- 2013–2014: The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Hollingsworth v. Perry re-legalizes same-sex marriage in California. Seven states legalize it by legislative action or state court decision. The Supreme Court's decision providing federal benefits for same-sex marriages in United States v. Windsor, while not saying that there is a constitutional right to same-sex marriage, is widely cited as precedent by judges who do say so. Oregon and Pennsylvania decline to appeal such decisions, and five states' appeals are declined by circuit courts, and declined to be heard by the Supreme Court.

Transcript

- [A graph with the x-axis showing time in years from 1940 to some time after 2010 (presumably ca. 2014). The y-axis shows percentage of population. The graph has 4 lines, 2 solid and 2 dashed, with 2 different colors: red and blue. The red lines indicate statistics concerning interracial marriage, while the blue indicate statistics concerning same-sex marriage. The solid lines indicate population living in states where that type of marriage is legal, while the dashed lines indicate popular approval of that type of marriage based on various polls.]

- [Solid red line:] Percentage of US population living in states with legal interracial marriage

- [Dot on solid red line:] Full legal access: 1967

- [Dashed red line:] Popular approval of interracial marriage (Source: Gallup Polls)

- [Dot on dashed red line:] Majority approval: 1995

- [Dashed blue line:] Popular approval of same-sex marriage (Source: various polls)

- [Dot on dashed blue line:] Majority approval: 2011

- [Solid blue line:] Percentage of US population living in states with legal same-sex marriage

- [Interracial marriage is indicated as being more than 50% legal in 1940, with a very slight downward trend that spikes up slightly ca. 1948, then trends slowly upward to about 65% until ca. 1967, at which point it spikes directly to 100% legality and remains there through 2014. Popular approval of interracial marriage is below 10% in the late 1950s, rising steadily to approximately 40% in 1980, then continuing to rise more slowly to the majority approval point in 1995, and spiking up to about 65% ca. 1997, plateauing until ca. 2003, rising quickly again to about 75% ca. 2006 and rising generally upward to the final ca. 2014 statistic depicted between 85% and 90% popular approval. The visual effect seems to be a wide gap of time between legalization of and popular approval of interracial marriage. Popular approval appears to trail legalization by no less than 20 years at any given point.

- Popular approval of same-sex marriage (according to "various polls") is depicted first at about 15% ca. 1986, trending gradually upward until ca. 2000, where it plateaus between 35% and 40% to resume an upward trend ca. 2007, continuing steadily through majority approval in 2011 to a ca. 2014 value between 55% and 60%. The legality of same-sex marriage is indicated to start at 0% ca. 2002, then jumps quickly to plateau around 5% until ca. 2008, at which point it spikes up to between 15% and 20%, then plummets to just above than 5% by ca. 2009, jumping quickly back up to between 15% and 20% between ca. 2010 and 2011, then trending upward even more quickly to end at about 55% legality ca. 2014. The visual effect seems to be a more turbulent line for legality of same-sex marriage than any of the other trends, which also seems to be quickly closing on the popular approval trend. Popular approval has preceded legalization by nearly 20 years at certain points, but the trends appear to be closing and may intersect by 2015 or 2016.]

Trivia

- Though rendered ineffective by the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, the constitutions of South Carolina and Alabama still contained language prohibiting miscegenation until the turn of the century; the language was removed by a majority referendum in 1998 for South Carolina and in 2000 for Alabama.

Discussion

Okay, that was the hardest explanation I've attempted so far. Cheeselover724 (talk) 04:42, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- Graphs tend to be hard. On that note, the transcript was tricky and probably needs work. Athang (talk) 05:14, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- Hope you don't mind, I just about completely rewrote the transcript, attempting to indicate the structure of each line and the visual effect I thought was intended -- Brettpeirce (talk) 11:41, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- looksclike Gallup has a nice page up right now that happens to include gay marriage and interracial marriage one below the other. Probably good to use these in the explanation?

http://www.gallup.com/poll/117328/marriage.aspx Sean timmons (talk) 21:05, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

Thank you for your efforts. This of course raises questions about what's next. Let's hope we can question sincerely and this does not become a troll.

How about adoption of children by single persons (authorized in France, where else) ? By same-sex couples (authorized in France because the same law applies to marriage and adoption) ? Can anyone (even Randall) gather data and produce a graph ?

Adoption normally gives a home with proper parents to a child that lack them by accident.

Notice that every human person living or dead has exactly one mother and one father because of the Gamete mechanism (even if one or even both parents are sometimes unknown or the person is raised by other people). United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child article 7 mentions "The child (...) immediately after birth (...) shall have the right (...) to know and be cared for by his or her parents."

In the US one can buy a child specifically produced to be adopted. Depending on the situation, children are produced using gestational surrogacy or Assisted reproductive technology.

In theory this has nothing to do with sexual orientation of the buyers. In practice fertile couples just have babies naturally. So the only people who buy babies are very rich people who want babies with specific features (keyword "screening"), infertile couples and people that may be technically fertile but whose situation is not a traditional couple (they may be single or same-sex couple). I know in my town two gay men that bought two children in the US.

Those children are produced to be deprived of one of their parents. That violates Template:UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, right ? Is that a progress ? How to solve that ?

Let's try to remain close to this XKCD graph and the question: what's next and what to think of it ? Open to your constructive questions and comments. --MGitsfullofsheep (talk) 11:44, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- So you're saying that adoption (from gay or straight couples) violates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child? That all sperm donation should be banned? Diszy (talk) 12:17, 8 October 2014 (UTC) Also, the US has not ratified the UNCRC so this discussion is moot. You can't hold them to the rules if they blatantly declare that they don't follow them.Diszy (talk) 12:25, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- Thank you for your reply Diszy.

- > So you're saying that adoption (from gay or straight couples) violates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child?

- No, I'm not saying that. The case of babies produced and sold, even after many debates, seems somehow wrong in a way that has nothing to do with sexual orientation of parents.

- When a child has no suitable genetic parents (they are dead or abusing) I understand that adoption is clearly compatible with UNCRC article 7.

- When a child is produced to be deprived of one parent, I find it debatable. Or maybe we can save the logic by considering that the genetic parent "resigns" their responsibility, which falls back to the previous case.

- > That all sperm donation should be banned?

- I'm not discussing if it should be banned, but you raise an interesting point.

- Technically, a spem donor is a genetic parent that "resigns" (can anyone find a better word) their responsibility as parent since they are not planning to honor it (some do, afterwards). Does it violate UNCRC article 7 ? My understanding is: things are blurred by the "as far as possible" wording.

- > Also, the US has not ratified the UNCRC so this discussion is moot.

- moot - "of little or no practical value or meaning;

- interesting only from the point of view of theory:"

- Thank you for this piece of information. So this can't be used to demonstrate that US legal system is inconsistent.

- > You can't hold them to the rules if they blatantly declare that they don't follow them.

- I didn't know that.

- Again I'm not discussing good and bad or whatever, rather logical consistency. This is a math-geek-language discussion place, isn't it ?

- There's one way countries who have ratified the UNCRC could claim it's okay.

- They could claim that the "parents" in article 7 are not genetic parents but the persons who are willing to raise the child. Though that's another possible way to make a consistent logical model, I'm pretty sure that's not what the UN had in mind when they wrote this.

- Thank you again for your feedback.

- --MGitsfullofsheep (talk) 15:04, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

It's interesting to think about the differences between interracial marriage versus gay marriage. In the latter situation an entire class of people aren't able to obtain the only type of marriage that would likely appeal to them, whereas I think interracial marriages are more "fungible" (definitely not the right word) in that a person who engages in an interracial marriage may not have a strong preference for interracial marriages over intraracial marriages. So in banning interracial marriage, they impacted specific individuals, but there wasn't a well-defined class of interracial marriage pursuers who were denied the right to marry. I think this is relevant because in the case of gay-marriage, most people in the wronged class (people who want gay marriages), and many people outside of the wronged class, all support the right. With interracial marriage on the other hand, I would be curious to see if it was mostly whites that opposed interracial marriage, or if large percentages of whites, blacks, and other minorities also disapproved of interracial marriage.

173.245.54.194 15:21, 8 October 2014 (UTC)XkdcPoster

So legalization of inter-racial marriage preceded (by quite some time) the general acceptance of it. While acceptance of same-sex marriage is preceding it's legalization. An interesting switch in how the country operates. A consequence of the rise of groups like the "conservative" Tea Party folks and the increased radicalization of the right? Where once we had politicians who did the right thing despite its not being popular, now delay doing the right thing because they are far more interested in "leading by following" than in actual leading? 199.27.128.117 15:45, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- The right hasn't changed. Only the left has radicalized. No politician has ever done the right thing, for any reason. 172.68.12.108 (talk) 01:42, 20 April 2025 (UTC) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Some say radicalization, some say marginalization. Perhaps both are right.Seebert (talk) 17:48, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

- Yeah, both are right in that one eventually leads to the other. Folks who get too radical (in either direction) get marginalized. But it's a self-inflicted marginalization and an appropriate one. 199.27.128.117 16:45, 9 October 2014 (UTC)

- Not self-inflicted and not appropriate. 172.68.12.108 (talk) 01:42, 20 April 2025 (UTC) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Likewise, prolonged exclusion of a group of people may cause them to become radical. Spur (talk) 02:54, 10 October 2014 (UTC)

- Yeah, both are right in that one eventually leads to the other. Folks who get too radical (in either direction) get marginalized. But it's a self-inflicted marginalization and an appropriate one. 199.27.128.117 16:45, 9 October 2014 (UTC)

Although I agree with Randall's point in this comic, he is cheating a little bit. The poll questions are slightly different: "do you approve of interracial marriage?" vs "do you think same-sex marriage should be legal?" People who "disapprove" of something, but grudgingly acknowledge that it should be allowed, are miscounted. - Frankie (talk) 18:22, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

p.s. OTOH, hypothetically if SCOTUS reversed Loving and allowed interracial bans again, a lot of those disapprovers would probably turn back into active opponents. IOW, they accept it as law mainly because they know they can't change it. - Frankie (talk) 18:26, 8 October 2014 (UTC)

I approve of interracial marriage, but not same-sex marriage. 172.69.34.16 18:27, 3 April 2023 (UTC)

- That's nice of you. But can we presume you're otherwise happy with congress (of all kinds)? 172.70.85.225 21:34, 3 April 2023 (UTC)

Add comment

Add comment