1489: Fundamental Forces

| Fundamental Forces |

Title text: "Of these four forces, there's one we don't really understand." "Is it the weak force or the strong--" "It's gravity." |

Explanation[edit]

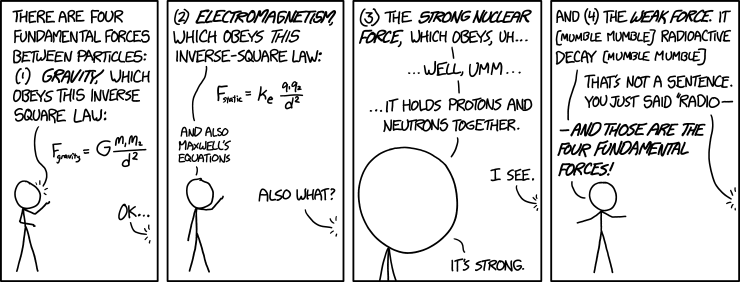

Cueball is acting here as someone teaching physics at a basic level, perhaps a high school science teacher. He seems to understand the general idea of the four fundamental forces, but his understanding gets progressively more sketchy about the details. The off-panel audience, probably a student or class, is interested, but quickly begins to realize Cueball's lack of understanding. Instead of acknowledging the problem directly, Cueball simply blusters onwards.

The comic also outlines how progressively difficult it gets to describe the forces. Gravity was first mathematically characterized in 1686 as Newton's law of universal gravitation, which was considered an essentially complete account until the introduction of general relativity in 1915. The electromagnetic force does indeed give rise to Coulomb's law of electrostatic interaction (another inverse-square law, proposed in 1785), but a much more comprehensive description, covering full classical electrodynamics, was only given in Maxwell's equations around 1861. The strong and weak forces cannot easily be summarized as comparably simple mathematical equations. It's possible that Cueball does understand the strong and weak interactions, but is completely at a loss when he tries to summarize them.

The strong force doesn't act directly between protons and neutrons but between the quarks that form them. Unlike gravity and electromagnetism, the strong force gets stronger with increasing distance: It is loosely similar to the restoring force of an extended spring. However, all stable heavy particles are neutral to the strong force, due to being made up of three "colors" (or a color and the appropriate "anticolor") of quarks. Between protons and neutrons there is a residual strong force, analogous in some ways to the van der Waals force between molecules. This residual strong force is carried by pions and does decrease rapidly and exponentially with distance due to the pions having mass.

The weak force is much weaker than electromagnetism at typical distances within an atomic nucleus (but is still stronger than gravity), and has a short range, so has very little effect as a force. What it has instead is the property of changing one particle into another. It can cause a down quark to become an up quark, and in the process release a high-energy electron and electron anti-neutrino. This is known as beta decay, a form of radioactivity. Over even shorter distances, and much higher temperatures, the weak interaction and electromagnetism are essentially the same, thus being merged to form the electroweak force. The electroweak force was also mentioned in a later comic, 1956: Unification.

The title text touches upon a strange paradox regarding gravity: in isolation it is the simplest and easiest to understand of the four forces, with well-understood equations that can be taught to the layman with clear-cut examples (as it is the one force everyone experiences on a regular basis). However when taking other forces into account gravity turns out to be the hardest to reconcile with a coherent (quantum) understanding of all four forces together.

Transcript[edit]

- [Cueball is holding his hands up while giving a lecture to an off panel audience.]

- Cueball: There are four fundamental forces between particles:

- (1) Gravity, which obeys this inverse square law:

- Fgravity = G m1m2/d2

- (1) Gravity, which obeys this inverse square law:

- Off panel audience: OK...

- [Cueball is still holding his hands up while continues the lecture to the off panel audience.]

- Cueball: (2) Electromagnetism, which obeys this inverse-square law:

- Fstatic = Ke q1q2/d2

- ...and also Maxwell's equations

- Off panel audience: Also what?

- [Zoom in on Cueball as he continues the lecture to the off panel audience.]

- Cueball: (3) The strong nuclear force, which obeys, uh ...

- ...well, umm...

- ...it holds protons and neutrons together.

- Off panel audience: I see.

- Cueball: It's strong.

- [Cueball finishes the lecture to the off panel audience and spreads out his arm for the final remark.]

- Cueball: And (4) the weak force. It [mumble mumble] radioactive decay [mumble mumble]

- Off panel audience: That's not a sentence. You just said “Radio-

- Cueball: – And those are the four fundamental forces!

Discussion

«The off-panel audience, probably a student or class, is interested, but quickly begins to realize Cueball's lack of understanding. Instead of acknowledging the problem directly, Cueball simply blusters onwards.»

My interpretation is rather different. It looks like Cueball is a physicist who knows that the distinction of "four fundamental forces" is basically wrong/obsolete (the term "force" is not even used anymore in theoretical physics), but since his audience are high school students, he can't go into the many complex details underlying the fundamental interactions, and therefore is forced to gloss over it. This is confirmed by the title text (if Cueball didn't understand the theory of fundamental interactions, he wouldn't give that answer). --188.114.101.78 10:31, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

To me it appeared as a typical exam situation for Cueball with him being the pupil. And ironically that situation looks similar to the real scientific understanding of the topic. Renormalist (talk) 11:12, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

- I could see that, to an extent - it doesn't jive with the title text IMO, and it's less funny that a student would be glossing over this stuff than a someone in an instructive role, but I could see it -- Brettpeirce (talk) 11:46, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

Irony like this is not uncommon in physics. What was the first encounter with electric phenomena? Triboelectricity. What don't we understand at all? Right. Or take Zenos paradoxon. Or the divisibility paradoxon. The oldest nuts tend to be the toughest. 108.162.230.221 12:26, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

- Those paradoxes are perfectly explained through calculus. Zeno's requires only algebra. 108.162.219.100 06:13, 24 February 2015 (UTC)

- I'm not sure about the first one, but one of first electromagnetic phenomenons we encountered was light. We first observed it about 200000 years ago. :P 141.101.104.77 13:45, 21 February 2015 (UTC)

- The first electromagnetic phenomenon we encountered was the the propagation of electric signals along the neuron's axon toward synaptic boutons situated at the ends of an axon. It was literally the first thing we experienced, as there can be no experience without it. However, the triboelectricity was the effect the electricity was named AFTER. -- Hkmaly (talk) 06:48, 14 October 2021 (UTC)

I knew from the title, "Fundamental Forces", that this was going to be a great one. 199.27.128.200 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

I prefer Chromatic Force and Flavor Force. Why use weak names when we have new strong ones? 108.162.254.98 11:58, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

In high school Physics, my class was taught that physicists had recently combined the Electromagnetic and Weak Nuclear forces into the Electro-Weak Force, so there were only three and if we were to find the Higgs Boson, there might be just two or one. 108.162.241.11 21:55, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

- Actually, it is the Higgs Boson, that combines the electromagnetic and the weak nuclear interaction into the electroweak interaction, so it's still 3. But actually, even if electromagnetism and the weak interaction can be described in one theory, they are still viewed as two different phenomena, so it actually will always be 4. (Unless we discover other interactions). --141.101.105.192 22:23, 20 February 2015 (UTC)

- Old timer physicists say the same thing about magnetism and electricity. 141.101.64.35 16:53, 21 February 2015 (UTC)

Is it just possible that Randall posted this forum to see how we here actually try to explain strong and weak Forces? 188.114.111.224 22:34, 21 February 2015 (UTC)

In the first panel, Cueball forgot to mention Einstein's field equations. 108.162.254.77 11:35, 22 February 2015 (UTC)

This comic and the ensuing discussion is more intriguing when the Chrome xkcd substitutions extension is turned on. Weak Horse, Strong Horse, Flavor Horse, Chromatic Horse... 199.27.128.194 01:57, 24 February 2015 (UTC)

couldnt the title text joke just be joking about how the professor doesnt know anything? like if hes just saying that from a quantum point of view that gravity is the hardest, then its not really a joke. the joke is its the only one he can describe easily, but then he says its the most difficult one. i think thats irony, but maybe not. but yeah thats just my tide whats yours.TheJonyMyster (talk) 03:57, 26 February 2015 (UTC)

When I read this comic, I see a metaphor for the scientific community's difficulties explaining these interactions to laymen. Cueball is a stand-in for scientists, and while he likely understands these concepts very well, has no earthly idea how to encapsulate them for someone who hasn't studied them in-depth. As the concepts become more abstract and unintuitive, Cueball's explanations become more incomprehensible to the increasingly vexed lay audience. Gravity is a phenomenon that is readily observable to anyone, and so the audience accepts it without question--note that Cueball's explanation doesn't really do the topic any better justice than his explanations of the other forces; he just doesn't need to. Electromagnetism is less intuitive to a layman, but its effects are still observable, so the audience, accepting it, seems more concerned that Cueball glosses over a hint that it's a bit more complex than his initial explanation would suggest. The explanations of strong and weak forces are no more coherent, but the complete lack of observable effects to laymen makes this lapse unforgivable to the audience. The alt text highlights the irony of this situation, where the lack of any comprehensible explanation of the strong and weak forces leads the audience to believe that they are not well-understood, but in fact it is gravity, the force they simply accepted without question, that is a mystery. 173.245.56.209 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

As a philosopher, my interpretation was not that Cueball "can't encapsulate" the ideas, but that no one really understands them, even specialists. Like Socrates was the expert ethicist simply by virtue of not knowing what the good is, Cueball (Monroe?) is the expert physicist because he refuses to bullsh** about which and how many are the most "fundamental" horses. The fact is that knowing the mathematical formula that describes the phenomenon doesn't constitute </b>understanding</b>. Same goes for gravity. Hence the scrollover punchline. CircularReason (talk) 14:55, 13 June 2015 (UTC)

I find a different humor in this than it seems the rest of you do. As an out of practice physicist now teaching high school physics this is word for word what I would have said should I have to explain the fundamental forces without researching any of the things that have slipped my mind. There is something about the way Randall captures the exact way I think (have been trained to think?) that had me guffawing at this comic and feeling a bit sheepish at 793: Physicists 173.245.56.164 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

What is a "fundamental horse"? Malamanteau314 (talk) 04:59, 6 November 2015 (UTC)

- There are four fundamental horses which we have a decent understanding of, but the one we understand the least is "Death". 108.162.238.76 01:36, 20 January 2016 (UTC)

- Death is the rider, not the horse itself. Mikemk (talk) 07:50, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

- The horses name is Binky. Andyd273 (talk) 14:00, 4 October 2016 (UTC)

- His name is Susan, and he wants you to respect his life choices. 03:47, 29 January 2017 (UTC)

- No. His name is Binky. L-Space Traveler (talk) 21:21, 26 April 2023 (UTC)

- His name is Susan, and he wants you to respect his life choices. 03:47, 29 January 2017 (UTC)

- The horses name is Binky. Andyd273 (talk) 14:00, 4 October 2016 (UTC)

- Death is the rider, not the horse itself. Mikemk (talk) 07:50, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

Should the explanation be updated to note the discovery of gravitational waves? Mikemk (talk) 07:50, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

For the record, this is, with only a very little exaggeration, exactly how the four fundamental fources were presented to me in high school. Spot on. -CDJ

This makes me think of FunTime from the Origami Yoda books. That stunk. 172.68.34.60 17:26, 7 February 2024 (UTC)