Difference between revisions of "2028: Complex Numbers"

TrueBoxGuy (talk | contribs) (Transcript) |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{{incomplete|Created by a MATHEMATICIAN - Do NOT delete this tag too soon.}} | {{incomplete|Created by a MATHEMATICIAN - Do NOT delete this tag too soon.}} | ||

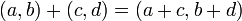

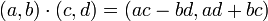

| − | The complex numbers can be thought of as pairs <math>(a | + | The complex numbers can be thought of as pairs <math>(a, b)\in\mathbb{R}</math> of real numbers with rules for addition and multiplication. |

| − | : (a,b) + (c,d) = (a+c, b+d) | + | : <math>(a, b) + (c, d) = (a+c, b+d)</math> |

| − | : (a,b) | + | : <math>(a, b) \cdot (c, d) = (ac - bd, ad + bc)</math> |

| − | As such they are | + | As such they are two-dimensional vectors, with an interesting rule for multiplication. The justification for this rule is to consider a complex number as an expression of the form <math>a+bi</math>, where <math>i^2 = -1</math>, i.e. ''i'' is the square root of negative 1. Applying the common rules of algebra and the definition of ''i'' yields rules for addition and multiplication above. |

| − | Regular | + | Regular two-dimensional vectors are pairs of values, with the same rule for addition, and no rule for multiplication. |

The usual way to introduce complex numbers is by starting with ''i'' and deducing the rules for addition and multiplication, but Cueball is correct to say that complex numbers are really just vectors, and can be defined without consideration of the square root of a negative number. | The usual way to introduce complex numbers is by starting with ''i'' and deducing the rules for addition and multiplication, but Cueball is correct to say that complex numbers are really just vectors, and can be defined without consideration of the square root of a negative number. | ||

| − | The teacher | + | The teacher (Miss Lenhard) counters that to ignore the natural construction of the negative numbers would hide the relevance of the fundamental theorem of algebra (Every polynomial of degree ''n'' has exactly ''n'' roots, when counted according to multiplicity) and much of complex analysis (the application of calculus to complex-valued functions), but she also agrees that mathematicians are too cool for "regular vectors." |

Revision as of 17:44, 3 August 2018

| Complex Numbers |

Title text: I'm trying to prove that mathematics forms a meta-abelian group, which would finally confirm my suspicions that algebreic geometry and geometric algebra are the same thing. |

Explanation

| This is one of 60 incomplete explanations: Created by a MATHEMATICIAN - Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

The complex numbers can be thought of as pairs  of real numbers with rules for addition and multiplication.

of real numbers with rules for addition and multiplication.

As such they are two-dimensional vectors, with an interesting rule for multiplication. The justification for this rule is to consider a complex number as an expression of the form  , where

, where  , i.e. i is the square root of negative 1. Applying the common rules of algebra and the definition of i yields rules for addition and multiplication above.

, i.e. i is the square root of negative 1. Applying the common rules of algebra and the definition of i yields rules for addition and multiplication above.

Regular two-dimensional vectors are pairs of values, with the same rule for addition, and no rule for multiplication.

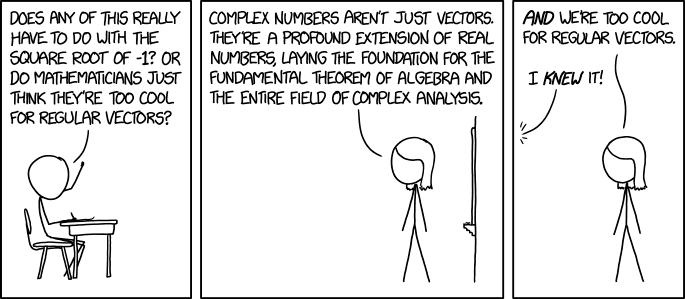

The usual way to introduce complex numbers is by starting with i and deducing the rules for addition and multiplication, but Cueball is correct to say that complex numbers are really just vectors, and can be defined without consideration of the square root of a negative number.

The teacher (Miss Lenhard) counters that to ignore the natural construction of the negative numbers would hide the relevance of the fundamental theorem of algebra (Every polynomial of degree n has exactly n roots, when counted according to multiplicity) and much of complex analysis (the application of calculus to complex-valued functions), but she also agrees that mathematicians are too cool for "regular vectors."

Transcript

| This is one of 43 incomplete transcripts: Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

- [Cueball (the student) is raising his hand and writing with his other hand. He is sitting down at a desk, which has a piece of paper on it]

- Cueball: Does any of this really have to do with the square root of -1? Or do mathematicians just think they're too cool for regular vectors?

- [Miss Lenhart (the teacher) is standing in front of a whiteboard, replying to Cueball's question]

- Miss Lenhart: Complex numbers aren't just vectors. They're a profound extension of real numbers, laying the foundation for the fundamental theorem of algebra and the entire field of complex analysis

- [Miss Lenhart is standing slightly to the right in a blank frame]

- Miss Lenhart: And we're too cool for regular vectors.

- Cueball (off-screen): I knew it!

Discussion

I assume this is strictly a coincidence, but in reference to the title-text, I'll just mention that Caucher Birkar [the mathematician whose Fields Medal was stolen minutes after he received it in Rio de Janeiro on Weds (1Aug2018)] received the award for work in algebraic geometry. Arcanechili (talk) 16:34, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

- Perhaps it's causal not coincidental. Medal theives and perhaps Randall might read the news also. [[1]] 162.158.79.209 00:34, 4 August 2018 (UTC)

I've added a basic description of Abelian groups in the title text, and that's about as much as I know about such topics. I'm not sure what a "meta-Abelian group" is, is that an Abelian group of other groups? Also, could someone add basic descriptions of algebreic geometry and geometrical algebra? 172.68.94.40 18:42, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

In the title text, since groups are a concept within mathematics, it seems odd to consider mathematics as a whole forming any sort of group within itself, which I suspect is the first part of the pun. Secondly, since groups involve the commutative property, I think the last part is a pun about the order of the words algebra and geometry, as if they're commutative themselves! Ianrbibtitlht (talk) 19:19, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

- I meant to say 'abelian' groups involve the commutative property, and the meta prefix is referring to the fact that it's about the names rather than the mathematical details - i.e. commutative in metadata only. Ianrbibtitlht (talk) 19:24, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

- I guess the joke is that informally mathematicians form a group (a number of people classed together), what would strictly be a set in mathematics. While in mathematics, a group is an algebraic structure consisting of a set of elements equipped with an operation that combines any two elements to form a third element and that satisfies specific conditions. --JakubNarebski (talk) 21:18, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

It's a false dilemma. Complex numbers are vectors ( is a two-dimensional

is a two-dimensional  -vector space, and more generally every field is a vector space over any subfield), but that doesn't change anything about the fact that

-vector space, and more generally every field is a vector space over any subfield), but that doesn't change anything about the fact that  is by definition a square root of -1. Zmatt (talk) 20:38, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

is by definition a square root of -1. Zmatt (talk) 20:38, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

Important concepts in math usually show up naturally in many apparently unrelated areas. Each area will name and define a concept that makes sense for the problems being considered. One of the joys of math is proving that multiple, apparently unrelated, definitions are equivalent. When definitions are equivalent you cannot pick "the one true definition" -- any of them will do. However the principle of maximum laziness leads to the one with the easiest notion being used as a canonical definition.162.158.75.130 18:17, 7 August 2018 (UTC)

Fun factoid: not only is  the unique proper field extension of finite degree over

the unique proper field extension of finite degree over  (since

(since  is algebraically closed), but the converse is true as well:

is algebraically closed), but the converse is true as well:  is the only proper subfield of finite index in

is the only proper subfield of finite index in  . They're like a weird married couple. Zmatt (talk) 20:53, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

. They're like a weird married couple. Zmatt (talk) 20:53, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

Altho there are no "meta-abelian" groups there are metabelian groups. If xy=yx then the commutator [x,y]=xyx^{-1}y^{-1}=1. The group generated by the commutators -- the commutator subgroup -- is thus a measure of how far a group is from being abelian. A metabelian group is a nonabelian group whose commutator subgroup is abelian. Thus a metabelian group is one made of a stack of two abelian groups. It is "meta-abelian" in that sense. A standard example is the group of invertible upper-trianglular matrices. The commutators all have 1s on the diagonals.

- One should note that the concept of complex numbers actually is older than vector spaces. So while it is true that complex numbers are a cool variant of vectors, historically that's not true, because vectors were more or less unknown when complex numbers were used for the first time. --162.158.90.6 09:59, 4 August 2018 (UTC)

Shouldn't the description of a group involve two operations? There is a binary operation that gloms two things together to make a new thing, but there's also a unary operation that takes only one thing and makes a new thing -- the inverse. Without the unary operation, you only have a semigroup.108.162.215.160 09:40, 5 August 2018 (UTC)

- No. The inverse operation arises as a consequence of the fact that it's a group. A group satisfies four conditions: 1. it is closed under the operation, 2. the operation is associative 3. there is an identity e such that a op e = e op a = a. 4. For every element a, there is a unique element b such that a op b = b op a = e. The inverse function falls out as a result of conditions 3 and 4 Jeremyp (talk) 10:26, 6 August 2018 (UTC)

Real numbers with regular multiplication is not a group, as zero does not have an inverse element. The example would work with addition --162.158.134.112 13:48, 9 August 2018 (UTC)Random guy who read the article