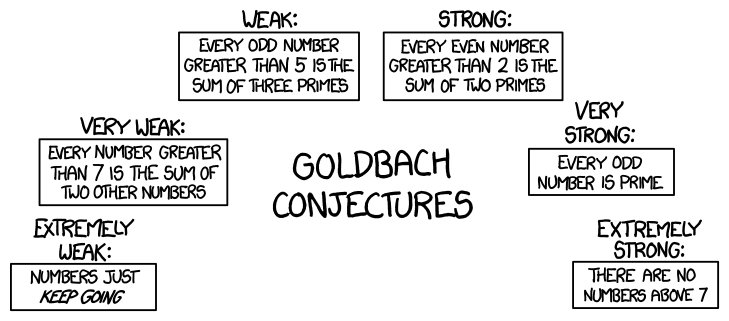

1310: Goldbach Conjectures

| Goldbach Conjectures |

Title text: The weak twin primes conjecture states that there are infinitely many pairs of primes. The strong twin primes conjecture states that every prime p has a twin prime (p+2), although (p+2) may not look prime at first. The tautological prime conjecture states that the tautological prime conjecture is true. |

Explanation

In mathematics, a pair of related conjectures may be described as "strong" and "weak" (or often, a normal statement and a "weak" one). A strong conjecture, if true, can be used to easily prove the weaker one, but not vice versa (i.e. if the weak statement is true, that alone isn't enough to prove that the strong one is also true). Conversely, if the weak conjecture is false, that is enough to prove the stronger one false as well, but not vice versa. Weak conjectures are often easier to prove than related strong ones.

Goldbach's weak and strong conjectures are a pair of real, unsolved problems relating to prime numbers (a number with exactly two positive divisors, 1 and itself). The comic states these under the labels "weak" and "strong".

- Goldbach's weak conjecture says that every odd number above 5 can be written as the sum of three prime numbers. A computer-aided proof of this was completed in 2013, but it is not yet clear whether the proof has been accepted as correct.

- Goldbach's strong conjecture (more often, simply "Goldbach's conjecture") says that every even number above 2 can be written as the sum of two prime numbers. If true, this would automatically make the weak conjecture true as well, because every odd number above 5 can be written as an even number above 2 (equal to two primes), plus 3 (the third prime).

Randall's further conjectures extend this to a whole series of progressively "weaker" and "stronger" statements. His weak conjectures are so weak that they are obviously true; his strong conjectures are so restrictive that they are obviously false. However, for the most part, they really do maintain a weak-strong relationship.

- The "very strong" conjecture says that every odd number is prime. This is false, because some odd numbers are composite (e.g. 9, 15, 21), and composite numbers are not prime. But if this conjecture were true, it would make Goldbach's (strong) conjecture true as well, because every even number can be written as the sum of two odd numbers (which, by this "conjecture", are prime).

- The "extremely strong" conjecture says that numbers stop at 7. This is false, but if it were true, it might make the above conjecture true as well: 9 is the first odd composite number, so stopping at 7 would eliminate all odd composite numbers. (1 is neither prime nor composite, but it has been counted as a prime number in the past. Randall may have meant 1 to be an unspoken exception, or he may be returning to the older definition that included 1 as prime.)

- In the other direction, the "very weak" conjecture says that every number above 7 can be written as the sum of two other numbers. This is true,[citation needed] but as it says nothing about primes, it isn't enough to prove Goldbach's weak conjecture. The weak conjecture being true would automatically make this one true, though (if we didn't already know it was true).

- The "extremely weak" conjecture says that "numbers just keep going". This is true, but it may not actually be implied by the above conjectures. Those say that numbers above 7 have certain properties, without requiring that such numbers exist. This may seem like a nitpicky point, but mathematicians love those; it also causes problems, because the "extremely strong" and "extremely weak" conjectures contradict each other. If the other conjectures were rewritten to say "these numbers exist, and have these properties", then they would imply this "extremely weak" conjecture, but then the "extremely strong" one would have to be stricken off.

The title text gives the same treatment to the twin prime conjecture, which says that there are infinitely many pairs of primes where one is 2 more than the other (e.g. 3 and 5). The title text adds a "weak" conjecture, according to which there are simply infinitely many pairs of primes (with no mention of the distance between them). This is true; Euclid's theorem says that there are an infinite number of primes, and so you can simply pick any two (e.g. 5 and 13) and call them a pair.

It also adds a "strong" conjecture where every prime is now a twin prime. This is easily proven false; 23 is prime, for example, but cannot be one of a pair as neither 21 nor 25 are. However, Randall adds a humorous hedge that some prime numbers "may not look prime at first".

Lastly, the tautological prime conjecture states that it itself is true while making no statement about primes. It is not technically a tautology but more of a plain assertion. Randall has mentioned tautologies before in 703: Honor Societies.

History of Goldbach's conjecture

Mathematician Christian Goldbach wrote a form of his conjecture (the "strong" one of the comic) in a letter to the famous Leonhard Euler in 1742. Euler replied that he considered it certainly true, but that he could not prove it.

Mathematicians have been solving related problems that are "weaker" than Goldbach's weak conjecture and working towards "stronger" ones. For example, in 1937 the weak conjecture was proven for odd numbers greater than 314348907. In 1995 a version was proven based on the sum of no more than seven prime numbers, and in 2012 the ceiling was lowered to five primes. In 2013 the weak conjecture was claimed proven for numbers greater than 1030, while all numbers below 1030 have been verified by supercomputers to satisfy the conjecture; these together imply that the weak conjecture is true, although there is no general proof of it for all numbers. Goldbach's strong conjecture remains unsolved.

Transcript

- [Six small panels with captions are arranged in an arch shape:]

- [Caption under the arch:]

- Goldbach Conjectures

- [Captions in the panels, from left to right:]

- Extremely weak:

- Numbers just keep going

- Very weak:

- Every number greater than 7 is the sum of two other numbers

- Weak:

- Every odd number greater than 5 is the sum of three primes

- Strong:

- Every even number greater than 2 is the sum of two primes

- Very strong:

- Every odd number is prime

- Extremely strong:

- There are no numbers above 7

Discussion

If a bot can create the text I read here, we have made great strides in artificial intelligence. Probably a human editor forgot to change the "incomplete/incorrect" heading. Tenrek (talk) 05:53, 30 December 2013 (UTC)

- Yes, I'm a bot. 199.27.128.62 21:42, 30 December 2013 (UTC)

I thought that {{incomplete|Created by a BOT}} means that the template was inserted by a BOT. 173.245.50.84 13:55, 30 December 2013 (UTC)

- It does mean that. But as others edit the page, they should keep the "incomplete" reason up-to-date. I've changed it to "incomplete|surely not quite complete yet..." ;) Nealmcb (talk) 14:28, 30 December 2013 (UTC)

It all seems to work except that the extremely strong seems to imply the opposite of the extremely weak Djbrasier (talk) 02:19, 31 December 2013 (UTC)

- I think the mistake is in the implication of the very weak to the extremely weak version. In fact, if there is any connection between those two statements it is an implication that goes the other way round. If the extremely strong version is true, we are not looking at the natural numbers. Thus, "Every number greater than 7 is the sum of two other numbers." does not imply "Numbers just keep going.", at all. (Also this accounts for no numbers at all, so the very weak version would still be correct.) Then there is the case that the extremely strong version is false. An implication from something false to anything is always true. --173.245.53.200 07:30, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

---I disagree with this, as it is not incorrect to say that "numbers keep going towards seven" as there are an infinite number of numbers approaching 7. Also, the extremely weak conjecture could easily refer to numbers in the negative direction only. 173.245.54.61 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

I always find it amusing that people assume that something phrased 'scientifically' is therefore right, whereas something phrased unscientifically (eg religious beliefs taken on faith) are automatically wrong. There seems to be an unexamined assumption that science is some magical dark art for uncovering infallible truths. Of course science is really just a methodological system for testing theories. Whenever I try to explain this concept, I try to come up with a general, untestable (non-scientific) assertion that is nonetheless true, alongside a very specific, repeatedly testable (falsifiable) assertion that is therefore eminently scientific, but which happens to be wrong. (Eg "it sometimes rains on Wednesday" and "it rains at least 100mm every Wednesday in Riyadh"). So for me this comic is a commentary on that principle - that the "strength" of a statement is only really impressive if it has also survived testing. Tarkov (talk) 10:47, 31 December 2013 (UTC)

- The assumption is not "that science is some magical dark art for uncovering infallible truths" but that science works. Bitches. Also, the example you have given is quite bad considering that your first statement is so vague that it is essentially meaningless and apparently, what you want to say with your second statement is that falsifiable claims are falsifiable, which is pretty trivial. Finally, the statements that are phrased unscientifically are not assumed to be automatically wrong but they are impossible to be proven or disproven and are often worded so vaguely that nobody in the known universe knows just what the hell they are supposed to even mean. They are just empty phrases that carry no information whatsoever. --173.245.53.200 07:30, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

According to the strong twin prime conjecture, all positive numbers greater than one are prime, due to 2 and 3 both being prime and extrapolation on primes from there. Thus, this nearly proves the very strong Goldbach conjecture, excluding one. Should this be noted in the explanation? 108.162.237.4 02:08, 1 January 2014 (UTC)(Kyt)

- I don't know if it's worth complicating things to bring the matter up. It's potentially more complicated than a simple error; in Goldbach's day, people still sometimes thought of 1 as a prime number (which simplifies his conjectures). —TobyBartels (talk) 18:00, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

This also reminds me of those psychological tests that ask how you feel about this and that. 108.162.226.228 15:02, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

Don't forget the first rule of tautology club. --141.101.98.236 18:07, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

- Moved from explain

I disagree with this, as it is not incorrect to say that "numbers keep going towards seven" as there are an infinite number of numbers approaching 7. Also, the extremely weak conjecture could easily refer to numbers in the negative direction only. (Edited by some people.) --Dgbrt (talk) 18:18, 10 January 2014 (UTC)

"Therefore, the "extremely strong" conjecture could not possibly imply (however indirectly) the validity of the "extremely weak" conjecture, as it would if proved true."

- It can be argued that since the "extremely strong" conjecture is obviously a contradiction (as in the logical sense, "a formula that's always false"), thereby, can imply any other formula. That is, if p is always false, then (p->q) for any q is always true. In this sense, if the "strong" version gets proved somehow, you get an inconsistent logical system, in which each and every formula can be proved as true, including those weaker forms. 108.162.215.56 13:03, 9 February 2014 (UTC)

This sentence is problematic: "The weak conjecture does not, however, imply the strong conjecture." "A does not imply B" technically means "A and not B" which, I'm sure, isn't what was meant. I added "in any evident way" which I think corrects it. 199.27.133.59 08:52, 10 July 2014 (UTC)

The paradoxical prime conjecture states that the paradoxical prime conjecture is false. --108.162.250.220 07:58, 12 October 2014 (UTC)

KYT's conjecture - prime numbers pattern

KYT's conjecture is described as follows:

a is a positive integer and is even, a>=8, b=a+18, a=c+D, c, D,E are prime numbers.

a=c+D b=c+E

E=D+18=b-c

There must be a prime number c that satisfies the two equations above. More examples are as follows:

10=3+7;5+5 28=5+23;11+17 46=3+43;5+41;17+29;23+23 64=3+61;5+59;11+53 ;17+47;23+41 82=3+79;11+71 ;23+59;29+53;41+41

Hello, I am not a regular user here (I have no account), but I am a working analytic number theorist. Harald Helfgott's proof of the ternary (i.e., weak) Goldbach conjecture has indeed been accepted as correct.

162.158.126.204 12:26, 27 August 2024 (UTC) Frank Thorne