1162: Log Scale

Explanation

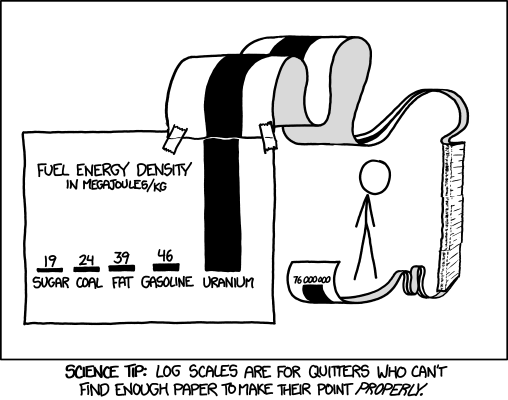

This comic strip is a tip, specifically the first science tip. As with most of Randall's tips, it is technically interesting for some applications but not very practical.

Uranium is stated to have 76 million MJ/kg, while the next highest material shown on the graph (gasoline) has 46 MJ/kg. Thus the uranium graph should be taller by a factor of 76,000,000/46 = 1.652 million. So, if the gasoline graph were 9mm in height, the uranium graph should be a bit more than 14.868 million mm tall, or nearly 15 km (9.2 miles) tall. Thus the need to fold the paper.

It should be noted that the method of extracting energy from the first 4 materials (combustion) is completely different from the method used with uranium (nuclear fission). If the technology existed to use nuclear fusion, then the first 4 materials would yield a higher energy density than uranium.

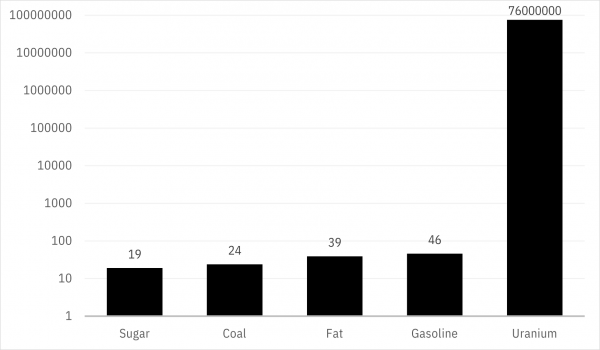

A log scale is a way of showing largely unequal data sizes in a comprehensible way, using an exponential function between each notch on the y axis of a graph. So for example the first on a Y axis of a graph using a log-10-scale would be 1, then 10, then 100 and 1000 for the fourth. A log/logarithmic function is the inverse of a corresponding exponential function. A log-scale version of the chart in the comic would look like this:

The log scale can also be abused to make data look more uniform than it really is. On a log scale the energy density of uranium looks larger than that of the other materials, but not dramatically so. The joke is that if one wanted to make their point "properly," they would go ahead and use ridiculous amounts of paper to show the difference between bars using a linear scale; this method would focus more on the shock factor of the differences in question, and less on actual communication/representation of data. Cueball seems to be passionate about the MJ/kg of uranium, so he would rather demonstrate the grandeur of the data than use a more efficient scale.

See these examples for well known day-to-day measurements which are measured on a log-scale.

The title text mentions computer scientist Donald Knuth; the fictional notation is a parody of Knuth's up-arrow notation. Using paper thickness as the basis for a log scale would probably give the exponential function a very large base. However, it can be noted that Knuth's up-arrow notation can handle numbers far, far larger than this paper stack notation; for example the number 3↑↑↑3, also known as Tritri[1], very compact in up-arrow notation, would require a number of iterations pinned to the stack on the order of several trillion. 3↑↑↑↑3 , also known as Grahal[2], would require a number of iterations that is not only too large to write down, but attempting to write that number using the same paper stack notation would require printing off a second stack of several trillion iterations just to hold the number pinned to the first stack. By repeating this multi-stack repetition, you reach the limit of up-arrow notation.

It should be noted that Randall has used log scales in past comics.

Transcript

- [A bar chart on a piece of paper, with a second piece of paper attached to it.]

- [Title of the bar chart] fuel energy density of different materials in megajoules/kg

- [Values of the first 4 bars on the paper] 19 24 39 46

- [The different bars for Sugar, Coal Fat and Gasoline and Uranium on a linear scale with the bar for Uranium exceeding on the attached stack of paper]

- [Labels of the 5 bars on the paper] Sugar Coal Fat Gasoline Uranium

- [The uranium bar on the chart goes off the page onto a huge strip of paper folded up into a stack slightly taller than Cueball.]

- [Value on the top end of the paper strip] 76 000 000

- [Caption below the panel:]

- Science Tip: Log scales are for quitters who can't find enough paper to make their point properly.

Trivia

This comic was seen in the What If? book, taken from "a certain webcomic".

Discussion

The fictional notation MAY BE a parody of Knuth's up-arrow notation - and uranium MAY BE an effective energy source. By the way, labeling the energy sources just with material name is insufficient: how good energy source is hydrogen? -- Hkmaly (talk) 09:17, 18 January 2013 (UTC)

- It has a calorific value of about 150 kJ/gm(much higher when compared to coal,etc.) but is too explosiveGuru-45 (talk) 14:24, 18 January 2013 (UTC)

- That is for burning it I assume? But what if you use it as fuel in a fusion reactor? Or an H-Bomb for that matter?

- is it really a parody? (well, probably arrow notation grows much more, here there is just a log log log etc) --.mau. (talk) 14:10, 18 January 2013 (UTC)

The calorie standard is defined by burning. So comparison doesn't fit with the graph as written. DruidDriver (talk) 20:46, 24 January 2013 (UTC)

It's true that uranium has an extremely high energy density, which is of great importance for mobile power plants; however, nuclear fission has a lot of safety issues, especially for mobile power, which is why it is used only for stationary power plants and large military vessels, such as aircraft carriers and subs.

Hydrogen is pretty good when highly compressed so as to get high energy volume density as well, but that leads to problems too. Also, hydrogen leaks more easily than almost anything else. That is especially a problem for an extremely flammable gas. On the plus side for hydrogen, nothing burns more cleanly.

- "The log scale can also be abused to make data look more uniform than it really is, so on a log scale sugar and other materials would look largely equal energy density when they clearly are not."

I think this is missing the point, which I take to be that displaying the data on a log scale would understate the vast difference between uranium and the hydrocarbons/carbohydrates:

E/m log(E/m) sugar 19 1.3 * coal 24 1.4 * fat 39 1.6 ** gas 46 1.7 ** uranium 76e6 7.9 ****.***

Uranium is clearly larger than the others, but only by a factor of 4, so the real magnitude of the difference may not be appreciated. With the stack of paper, he's proposing a way to show linear values for the data without having the uranium column simply shooting off the top of the page, with an arrow and the number. Wwoods (talk) 17:26, 18 January 2013 (UTC)

- or, he could just print at a scale that allows 76,000,000 to fit on the page, with the other values shown as near-infinitesimally thin lines. 67.51.59.66 18:23, 18 January 2013 (UTC)

A googolplex in Knuth's paper stack notation (based upon 3818 chr per page, and 25,824 pages to fill up a typical 8ft tall room), would be: 96.41816408 with a 2 pinned on it.

The algorithim is:

KnuthPaperStack(N): y = log10(N)/3818 If y >= 25824 Z = Z + 1 z = KnuthPaperStack(y) Return z,Z Else Return y,Z End if

--Markozeta (talk) 15:25, 20 January 2013 (UTC)

I think the name "Knuth paper-stack notation" sounds like "'Nuff paper-stack notation", meaning that it is a notation in which you need "enough paper" to stack up.

--NiccoloM (talk) 00:46, 21 January 2013 (UTC)

Isn't there a pun on Log which is itself an energy source as well as being the source of any reams of paper used to record values. 192.11.175.219 06:58, 22 January 2013 (UTC)

Am I the only one not seeing the glaring mistake on the comic? First thing I thought was "that stack of paper is not high enough!". Please someone double check my math: If the height has to be 6.6e6cm (stated above) at 29.7 cm each A4 (vertical), that would mean 222,222 sheets of paper one on top of another. Each stack of 100 pages is aprox 1cm high. That would represent the stack to be 2222cm high, ergo 22m, roughly a 7 story building. Unless there is the equivalent of 6 stories in the waving paper, or the length of the folding 7x that of an A4, or the stick figure is 7 times closer to the camera than the stack of paper is... THE HEIGHT OF THE PILE IS OH SO WRONG!!!!!! Please prove me wrong!

87.238.84.65 14:45, 28 January 2013 (UTC) Guest, 2nd time posting :)

Assumption #1) the graph is drawn on an 8.5 x 11 sheet of ordinary paper in landscape orientation.

Assumption #2) the graph is drawn in normal (linear) scale.

Assumption #3) Cueball is 6 feet tall.

Trusting MSPaint with the conversions, I read the first four bars to have about 5 units (megajoules per kg) per pixel. 76 million units divided by 5 units per pixel is a 15.2 million pixel tall bar.

Looking again to MSPaint, I read the 8.5" dimension of the paper to be about 193 pixels. 15.2 million pixels of graph bar divided by 193 pixels per page is 78756 pages.

Looking above, I read that 100 pages is 1cm, so our stack is going to be 787.56cm tall.

On this side of the pond, that's 310 inches, or about 25 feet.

So, the stack Cueball is looking at is too short to house an accurately long enough bar....

...IF the stack's footprint's longer dimension is only 8.5 inches. While the original graph paper appears to be 8.5x11, the ribbon of paper continuing the bar does not appear to be segmented. Again looking at MSPaint, it would seem the ribbon is about 4.75" wide. The stack is clearly much longer than it is wide. If the stack is 30" long and 4.75" wide, the stack would be whittled down to just over 6 feet tall.

So, making a gang load of assumptions, and scaling from an drawn image, it's reasonable to say the stack in the image could be accurate enough.

The explanation's assumption above that the gasoline bar is 4cm tall makes the piece of paper 96.5cm (38") tall, and that's just not practical. Using the scale I've based my statements on makes the gasoline bar just about 9mm.

-psychoboy70.164.66.64 19:57, 2 February 2013 (UTC)

What is the energy density of gasoline if it undergoes nuclear fusion? 173.245.48.91 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

This is similar to the iterated logarithm function, right? --199.27.128.192 21:28, 18 January 2015 (UTC)

I actually had to present this chart when I was ten years old, but I needed to use a split level to save paper due to the theme of environmentalism.141.101.104.186

The stated value of 76'000'000 MJ (76 Terajoules) per kg Uranium corresponds roughly to the energy released by the fission of U-235 nuclei of 202.5 MeV or 3.24·10-17 MJ per nucleus [[1]]. One kilogram of pure U-235 would release about 83 Terajoules. In a real nuclear power plant more energy is generated due to breeder reactions, so that per kg U-235 about 128 TJ are produced. One kilogram of natural uranium has about 0.71% U-235 and therefore the potential to produce about 910'000 MJ in a usual nuclear power plant. A fuel rod as used in a nuclear power plant (enriched to 3.5% U-235) has the potential to produce about 4.5 TJ. --162.158.150.231 01:19, 18 March 2016 (UTC)

What if the number of iterations doesn't fit the room? 141.101.80.74 21:25, 29 April 2016 (UTC)

- Case 1: The original paper stack doesn't fit the room. --> Pin a paper to it showing how many iterations you need to write it out.

- Case 2: The pinned paper stack doesn't fit the room. --> Pin a paper stack to THAT showing how many iterations you need to write it out.

- Case 3: That pinned paper stack doesn't fit the room. --> Pin a paper stack onto that showing how many iterations you need to write it out.

- etc.

625571b7-aa66-4f98-ac5c-92464cfb4ed8 (talk) 07:00, 8 March 2017 (UTC)