2026: Heat Index

| Heat Index |

Title text: The heat index is calculated via looking up the "effective temperature" in a table of air temperature and humidity values, and then adding a bunch more degrees because it feels WAY hotter than that. |

Explanation[edit]

Heat index, like wind chill, is a way to combine multiple factors, in this case temperature and humidity, to get a single number indicating what the air "feels like." This page gives a table, a formula, and lots more explanation.

Human skin does not directly detect temperature - only the rate of heat gain or loss. If you put pieces of metal, wood, and plastic at the same room temperature (cooler than the human body) the piece of metal feels cooler to the touch than a piece of plastic or wood - the metal conducts heat away from the higher body temperature at a higher rate than a good insulator does.

So in warm weather, it's not just the temperature that matters for comfort. The humidity and wind speed also factor into it. When humidity is high, sweat evaporation is less effective at cooling us off than in a "dry heat" with low humidity.

Hence, meteorologists use a combination of temperature and humidity to come up with the "heat index" value...and a combination of temperature and wind speed to produce a "wind chill" number.

Neither scale is particularly scientific in terms of measuring how people feel - but both are a more accurate representation of comfort levels than temperature alone.

The joke here is that these numbers seem entirely subjectively chosen - and in a sense, they really are, although they are calculated from an actual formula (a multivariate fit to a mathematical model of the human body - with nine terms!) and not by guesswork as the flow chart implies.

The title text suggests another way it is calculated: In general the effective temperature is calculated based on the conductivity of heat based on humidity. This is a legitimate method of determining how hot something feels because the heat conductance of water is higher than dry air and humans perceive more heat when the humidity is higher. But humans also tend to exaggerate and so Randall implies to add still a bunch more to satisfy the subjective sentiment.

Transcript[edit]

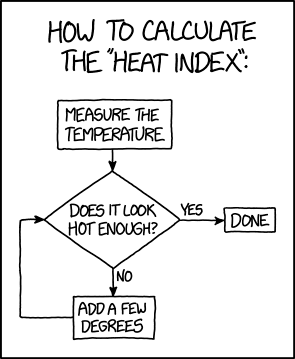

- [A flowchart is shown beneath its title:]

- How to Calculate the "Heat Index":

- [There are four boxes with arrows between. The first rectangular box is at the top, and an arrow points straight down:]

- Measure the Temperature

- [From there an arrow goes straight down to a decision diamond:]

- Does it look hot enough?

- [Two arrow goes out from the diamond. One goes straight down to another rectangular box. Both the arrow and the box has labels:]

- No

- Add a few degrees

- [From the bottom box an arrow goes back to the diamond. The other arrow from the diamond goes right to a final box with no arrows. Again both the arrow and the box has labels:]

- Yes

- Done

Discussion

Look at the formula, then at the table and try to tell with straight face that those tables were computed from the formulae and not the other way around. -- Hkmaly (talk) 22:38, 30 July 2018 (UTC)

- The Wikipedia page explicitely says that the various formulaes try to approximate the table. Can't be more explicit. 172.69.226.119 06:36, 31 July 2018 (UTC)

What confuses me is that even at 40% humidity the heat index is a lot hotter than the actual temperature. If 110 degrees at the lowest humidity that occurs commonly feels like 130 degrees, then what does it mean to feel like 110 degrees?Probably not Douglas Hofstadter (talk) 15:46, 31 July 2018 (UTC)

- 40% humidity is not a common level for places that typically reach 110f. For Phoenix, AZ, one of the few places that can reach both 110f and 40% humidity during the North American Monsoon, which is a small fraction of the summer, this is dealt with by nearly every indoor area being air conditioned, both to cool the air and to remove humidity. So, what it means for the "typical" 110f is what it feels like standing in front of your oven, rather than in front of a dishwasher on the drying cycle. And yes, 110 and 40% humidity is a severe weather event, and the National Weather Service routinely issues heat advisories and warnings in July and August. 172.68.47.36 23:59, 22 August 2018 (UTC)

Ironically, it is actually when humidity is at 100% (your sweat can't evaporate) that you feel the actual temperature. The lower humidity makes you feel cooler than the actual temperature. Similarly the windier it is (in cold weather) the more body heat is removed and the closer the actual temperature is to what it feels like. 162.158.62.141 21:31, 2 August 2018 (UTC)

I don't think it's accurate that "Human skin does not directly detect temperature - only the rate of heat gain or loss." Isn't it more that skin temperature is a dynamic equilibrium between the body's internal temperature and heat loss? I.e., skin feels colder in cold water than cold air because its equilibrium temperature is lower with faster heat loss? Also, is skin temperature even relevant here, or is it more about core temperature? JohnWhoIsNotABot (talk) 18:11, 3 August 2018 (UTC)

Could "add a few more degrees" be a pun on degrees of freedom, i.e. adding more variables to a meteorologist's model for heat index until it matches human perception closely enough? --172.68.133.180 22:23, 30 August 2018 (UTC)