Difference between revisions of "1709: Inflection"

JDspeeder1 (talk | contribs) m (→Explanation) |

(→Explanation) |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Explanation== | ==Explanation== | ||

| − | While walking, [[Megan]] tells [[Cueball]] that in {{w|inflected languages}} | + | While walking, [[Megan]] tells [[Cueball]] that in {{w|inflected languages}} — such as {{w|German language|German}} — changes in the spelling of a word changes its meaning, in a predictable way. Megan exemplifies this with how {{w|plural}} forms of {{w|nouns}} are created by sticking an "s" at the end, and {{w|past tense}} of a {{w|verb}} is done by the suffix "ed". Megan then explains that this works well in {{w|languages}} which build on {{w|alphabets}}. |

She continues to explain that their {{w|Indo-European languages|language family}} belongs to those that are inflected, but the {{w|Modern English|English branch}} is becoming less inflected than it used to be. Specifically this explains why English does not have so many {{w|Latin conjugations}}. A conjugation is a pattern of inflections, describing how a particular group of verbs is altered from its root form to represent different grammatical cases. Only verbs have conjugations (are ''conjugated''), nouns, pronouns, and adjectives are described by declensions (and are ''declined''). All inflected languages can be described by conjugations and declensions, although Latin is one of the most commonly cited, perhaps because Latin grammar was taught for centuries by monotonous rote learning of the conjugations and declensions. | She continues to explain that their {{w|Indo-European languages|language family}} belongs to those that are inflected, but the {{w|Modern English|English branch}} is becoming less inflected than it used to be. Specifically this explains why English does not have so many {{w|Latin conjugations}}. A conjugation is a pattern of inflections, describing how a particular group of verbs is altered from its root form to represent different grammatical cases. Only verbs have conjugations (are ''conjugated''), nouns, pronouns, and adjectives are described by declensions (and are ''declined''). All inflected languages can be described by conjugations and declensions, although Latin is one of the most commonly cited, perhaps because Latin grammar was taught for centuries by monotonous rote learning of the conjugations and declensions. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

! Present, Active, Indicative | ! Present, Active, Indicative | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |||

! | ! | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" | Singular | ||

! | ! | ||

| − | ! Plural | + | ! colspan="2" | Plural |

|- | |- | ||

! | ! | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

! ''they love'' | ! ''they love'' | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| | ||

| + | ! Perfect, Passive, Subjunctive | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" | Singular | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! colspan="2" | Plural | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! Latin | ||

| + | ! English | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! Latin | ||

| + | ! English | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! 1st person | ||

| + | ! 'amemor' | ||

| + | ! ''I should be loved'' | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! 'amemur' | ||

| + | ! ''we should be loved'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! 2nd person | ||

| + | ! 'amemaris' | ||

| + | ! ''thou should be loved'' | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! 'amemini' | ||

| + | ! ''you should be loved'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! 3rd person | ||

| + | ! 'ametur' | ||

| + | ! ''he/she/it should be loved'' | ||

| + | ! | ||

| + | ! 'amentur' | ||

| + | ! ''they should be loved'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | (The English singular uses archaic forms to highlight the number and person.) A complete conjugation includes all tenses (Present, Imperfect, Future, Perfect, Pluperfect, and Puture Perfect), both voices (Active & Passive), and all moods (Indicative, Imperative, Subjunctive). Other parts of speech — infinitives, participles, gerunds, and so forth — are needed to completely define the verb, but are not usually considered to be part of the conjugation. | ||

| − | + | Cueball then asks ''Could that mean that English writing might be ripe to become more pictographic?'' Instead of using traditional words, Megan replies with three {{w|emojis}} "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and a smiley — thus showing a pictographic version of the writing which has become more popular in the last years. Emoji has become a [[:Category:Emoji|recurring theme]] on xkcd. | |

| − | |||

| − | Cueball then asks ''Could that mean that English writing might be ripe to become more pictographic?'' Instead of using traditional words, Megan replies with three {{w|emojis}} "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and a smiley | ||

The writing systems of many languages have both {{w|pictographic}} and {{w|ideographic}} origins. "Pictographic" means that they are pictures of some thing that will remind the reader of either the pronunciation or the meaning of the word. The letter "A", for example, originated from a word meaning "ox", but was meant to remind readers of the glottal stop (it wasn't until the Ancient Greeks, who didn't have the glottal stop as a distinct phoneme, got a hold of the Phoenician version that it was transferred to the vowel(s) it is today). "Ideographic" means that they are designed, through pictures, to illustrate some idea. An example would be a "No Smoking" sign, where a red circle with a diagonal line is an abstract representation of "no". In fact, the three emojis used in the third panel of this cartoon are all ideographic, not pictographic, under this definition. "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and the smiley, are all emojis that remind us of a concept of approval. | The writing systems of many languages have both {{w|pictographic}} and {{w|ideographic}} origins. "Pictographic" means that they are pictures of some thing that will remind the reader of either the pronunciation or the meaning of the word. The letter "A", for example, originated from a word meaning "ox", but was meant to remind readers of the glottal stop (it wasn't until the Ancient Greeks, who didn't have the glottal stop as a distinct phoneme, got a hold of the Phoenician version that it was transferred to the vowel(s) it is today). "Ideographic" means that they are designed, through pictures, to illustrate some idea. An example would be a "No Smoking" sign, where a red circle with a diagonal line is an abstract representation of "no". In fact, the three emojis used in the third panel of this cartoon are all ideographic, not pictographic, under this definition. "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and the smiley, are all emojis that remind us of a concept of approval. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:20, 1 November 2023

| Inflection |

Title text: "Or maybe, because we're suddenly having so many conversations through written text, we'll start relying MORE on altered spelling to indicate meaning!" "Wat." |

Explanation[edit]

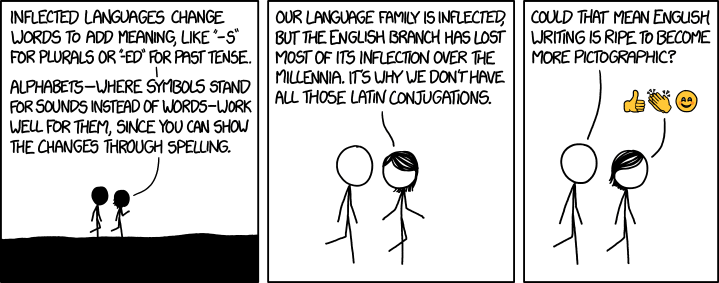

While walking, Megan tells Cueball that in inflected languages — such as German — changes in the spelling of a word changes its meaning, in a predictable way. Megan exemplifies this with how plural forms of nouns are created by sticking an "s" at the end, and past tense of a verb is done by the suffix "ed". Megan then explains that this works well in languages which build on alphabets.

She continues to explain that their language family belongs to those that are inflected, but the English branch is becoming less inflected than it used to be. Specifically this explains why English does not have so many Latin conjugations. A conjugation is a pattern of inflections, describing how a particular group of verbs is altered from its root form to represent different grammatical cases. Only verbs have conjugations (are conjugated), nouns, pronouns, and adjectives are described by declensions (and are declined). All inflected languages can be described by conjugations and declensions, although Latin is one of the most commonly cited, perhaps because Latin grammar was taught for centuries by monotonous rote learning of the conjugations and declensions.

A typical Latin conjugation would be the verb amare, to love.

| Present, Active, Indicative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||

| Latin | English | Latin | English | ||

| 1st person | 'amo' | I love | 'amamus' | we love | |

| 2nd person | 'amas' | thou lovest | 'amatis' | you love | |

| 3rd person | 'amat' | he/she/it loveth | 'amant' | they love | |

| Perfect, Passive, Subjunctive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||

| Latin | English | Latin | English | ||

| 1st person | 'amemor' | I should be loved | 'amemur' | we should be loved | |

| 2nd person | 'amemaris' | thou should be loved | 'amemini' | you should be loved | |

| 3rd person | 'ametur' | he/she/it should be loved | 'amentur' | they should be loved | |

(The English singular uses archaic forms to highlight the number and person.) A complete conjugation includes all tenses (Present, Imperfect, Future, Perfect, Pluperfect, and Puture Perfect), both voices (Active & Passive), and all moods (Indicative, Imperative, Subjunctive). Other parts of speech — infinitives, participles, gerunds, and so forth — are needed to completely define the verb, but are not usually considered to be part of the conjugation.

Cueball then asks Could that mean that English writing might be ripe to become more pictographic? Instead of using traditional words, Megan replies with three emojis "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and a smiley — thus showing a pictographic version of the writing which has become more popular in the last years. Emoji has become a recurring theme on xkcd.

The writing systems of many languages have both pictographic and ideographic origins. "Pictographic" means that they are pictures of some thing that will remind the reader of either the pronunciation or the meaning of the word. The letter "A", for example, originated from a word meaning "ox", but was meant to remind readers of the glottal stop (it wasn't until the Ancient Greeks, who didn't have the glottal stop as a distinct phoneme, got a hold of the Phoenician version that it was transferred to the vowel(s) it is today). "Ideographic" means that they are designed, through pictures, to illustrate some idea. An example would be a "No Smoking" sign, where a red circle with a diagonal line is an abstract representation of "no". In fact, the three emojis used in the third panel of this cartoon are all ideographic, not pictographic, under this definition. "Thumbs up" (like), "Applause", and the smiley, are all emojis that remind us of a concept of approval.

Egyptian hieroglyphics contain many pictorial elements, some of which are pictographic in the sense that they are meant to represent the thing that they picture, but many are more abstract (ideographic) or are used for their phonetic value (as "A" was used in early alphabetic systems). Similarly, in the Chinese character writing system, many of the elements have pictographic or ideographic origins; but they are often, and even usually combined in ways that are phonetic and not related to the pictures that were the origins of the characters.

Early modern English (think Shakespeare or the KJV Bible) used more forms for the tenses than we do today, which can help illustrate the trend away from inflected forms. In contrast, verbs in English today are often conjugated with auxiliary verbs. See below for details on modern verb conjugation in English.

The title text points out that some intentional misspelling are used in Internet slang to alter the meaning of a word: "what" becomes "wat" to express confusion, disgust or disbelief. The title text also uses typographical variation to emphasize the word MORE by using all capital letters. Such emphasis is difficult to show with inflected language alone.

This comic is referenced at 4500 BCE in huge chart of 1732: Earth Temperature Timeline. According to that comic it was at that time inflection was invented but just to tease future students so they have to remember a zillion verb endings.

Transcript[edit]

- [Cueball and Megan, holding a hand up, are seen walking together from afar in silhouette.]

- Megan: Inflected languages change words to add meaning, like "-s" for plurals or "-ed" for past tense.

- Megan: Alphabets—where symbols stand for sound instead of words—work well for them, since you can show the changes through spelling.

- [Zoom in on the two as Megan turns her head back towards Cueball and spreads her arms out.]

- Megan: Our language family is inflected, but the English branch has lost most of its inflection over the millennia. It's why we don't have all those Latin conjugations.

- [Cueball speaks as they walk on and Megan replies with three orange-yellow emoji: Thumbs Up Sign pointing right, Clapping Hands Sign pointing up left with two times three small lines to indicate the clapping and Smiling Face With Blushing (red) Cheeks and Smiling Eyes. Below given the closest match possible as of the release of the comic.]

- Cueball: Could that mean English writing is ripe to become more pictographic?

- Megan: 👍 👏 😊

Trivia[edit]

Modern verb conjugation in English[edit]

In the table below is a sample of a modern verb conjugation in English.

In all of these conjugations, the only inflections on the main verb "walk" are "-s", "-ed", and "-ing". The highly irregular helper verbs, "be" and "have", have somewhat more interesting inflections. And although this table shows only the third person, the first and second person would only introduce the helper verb "am" (as in "I am walking"); similarly, the table shows only the indicative mood, but the subjunctive and imperative moods would not introduce any additional words, and the conditional mood would only introduce the helper verb "would" (an inflection of the irregular helper verb "will") without any additional inflections on the main verb "walk". If instead we made this table in Spanish (for example), then there would be many more inflections on the main verb (12 in the third-person indicative alone, 45 including all persons and moods, if I didn't miscount).

| Voice-> | Active | Passive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tense | Singular (he/she/it) | Plural (they) | Singular (he/she/it) | Plural (they) |

| Present | walks | walk | is walked | are walked |

| Present progressive | is walking | are walking | is being walked | are being walked |

| Present perfect | has walked | have walked | has been walked | have been walked |

| Present perfect progressive | has been walking | have been walking | has been being walked | have been being walked |

| Past | walked | walked | was walked | were walked |

| Past progressive | was walking | were walking | was being walked | were being walked |

| Past perfect | had walked | had walked | had been walked | had been walked |

| Past perfect progressive | had been walking | had been walking | had been being walked | had been being walked |

| Future | will walk | will walk | will be walked | will be walked |

| Future progressive | will be walking | will be walking | will be being walked | will be being walked |

| Future perfect | will have walked | will have walked | will have been walked | will have been walked |

| Future perfect progressive | will have been walking | will have been walking | will have been being walked | will have been being walked |

| Conditional | would walk | would walk | would be walked | would be walked |

| Conditional progressive | would be walking | would be walking | would be being walked | would be being walked |

| Conditional perfect | would have walked | would have walked | would have been walked | would have been walked |

| Conditional perfect progressive | would have been walking | would have been walking | would have been being walked | would have been being walked |

Discussion

- It's also misleading to describe Chinese as a 'pictographic' language. The reason is that very few of the Chinese characters, as I recall from when I was studying it fewer than 100, are actually pictograms, that is to say an attempt to draw a picture of the thing in question. Some of these are 口 (kou, 'mouth'), 言 (yan, 'word', a picture of a mouth with sounds coming out of it), 日('ri', the Sun), 月 ('yue', the Moon), and some others. Then there is a somewhat larger group of characters best described as 'ideographs', that try to convey the meaning of the word symbolically, such as 中 ('zhong', middle), or which try to convey an idea using two or more other characters that may or may not themselves be pictograms. Examples of the latter would be 好 ('hao', good, with the character for 'mother' on the left and that for 'child' on the right), and 明 ('ming', bright, combining the characters for Sun and Moon above). But the vast majority of Chinese characters consist of a phonetic component, a part that is another character in its own right that conveys the sound (or conveyed it in ancient Chinese although the pronunciation may have shifted) and a part that gives a general notion of the meaning (called the radical). An example would be 钥 ('yue', key, composed of the character for the Moon (above) having the pronunciation 'yue', and the radical on the right which by itself means 'metal', so a metal thing that is pronounced 'yue'.

- I'm not sure how to handle this. The description above is more complicated than should appear in the main article, but the main article as written is somewhat misleading as to the role of pictograms in Chinese. Billjefferys (talk) 17:50, 21 July 2016 (UTC)

- Wow. You managed to write an entire dissertation on how Chinese isn't a pictographic language while managing to ignore the existence of Traditional Chinese and other previous reforms that simplified and standardised the brush strokes of the preceding writing form at the cost of losing the original resemblance to the object (eg 车/ 車). And you completely misunderstood how radicals affect pronunciation as shown from how your examples are contradictory. 141.101.98.5 20:48, 21 July 2016 (UTC)

- Please show how the radical in 钥 "affects the pronunciation". Here's a hint: The radical on the left is 金 ('jin', metal), and the phonetic part on the right is 月 ('yue', 4th tone, Moon). The character 钥 ('yue', 4th tone, key) is pronounced identically to 月. How has the presence of the radical affected the pronunciation if the two characters are pronounced identically? (And BTW this is a general rule, sometimes the tone changes, but it's not "because of the radical" since the same radical is used in different words, in some of which the tone may change and in others of which it does not.

- No, Chinese is not a pictographic language. The relatively few real pictograms have indeed been simplified through the fact that the brush was traditionally used to write the characters that were originally more or less realistic pictures of the objects (as archaeology has shown). And sure, the simplification has continued as in the example of 车/ 車 ('che' vehicle) that you give. But this has nothing to do with whether the language is pictographic. Again for example, by no stretch of the imagination can 钥 be considered a picture of a key.

- By concentrating on the fact that Chinese is written with a large set of characters, you miss the point. Most of these characters do not qualify as pictograms or even ideograms by any reasonable definition. They are just not constructed as attempts express in a picture the thing or concept being described (as emojis do attempt to do). The best you can say is that some Chinese characters (relatively few) are pictographic or ideographic, but that the vast majority use an entirely different principle of construction. Billjefferys (talk) 03:12, 22 July 2016 (UTC)

- Even calling characters like 口 pictographic is a stretch. Their origins are pictographic, but so are the origins of Latin alphabet letters. The most famous one is "A" that comes from the pictograph of the head of an ox. If Chinese had been pictographic, it would accept several mouth-shaped drawings as the morpheme "mouth", but in reality, the Chinese character 口 is not a drawing, it is a character, as symbolic and abstract as the letter "A". Chinese is a logographic language (even if logo- is misleading, it's more morpheme-writing than word-writing), no matter what the origins of the characters are. Lingu (talk) 11:19, 22 July 2016 (UTC)

- I agree fully with Lingu's comment. In fact I was going to say something about the pictographic origins of Latin alphabet letters like the famous 'A'. Lingu is correct to point out that it's the origins of the standard characters that is pictographic, namely they are based on pictures that were written long ago but have been stylized and conventionalized as well as modified over thousands of years.

- Some useful article from Wikipedia describe this in more detail. There is a piece from the Chinese Language article that briefly describes it, as well as the Chinese Characters article.

- Even the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing system is a whole lot more complex than implied by calling Egyptian hieroglyphics a "pictographic language", which is a misleading term, as this article shows. In addition to its pictographic elements, it has a lot of phonetic and other components.

- I think this paragraph needs extensive rewriting. The term "pictographic language" should be eliminated entirely and replace with something more accurate, such as "the writing system has significant pictographic origins". After all, it is the writing system, and not the language, that is related to pictographs and ideographs. And even many of the common emojis are more ideographic in nature than pictographic! Billjefferys (talk) 13:19, 22 July 2016 (UTC)

- Just wants to point out: the character 钥 is a simplified form; in traditional Chinese it is written 鑰, composed with the radical 金 and the sound 龠 (that is also pronounced "yue", and means a kind of musical instrument). To argue about how a Chinese character is formed, one should first identify whether this character is a simplified form or not. Simplified forms undergoes one more reform than traditional forms, so it is inaccurate to use them as examples on this.

- And, as a matter of fact, traditionally how a Chinese characters formed are classified in six categories; "pictogram" and "ideogram" are both the classification among them. The Wikipedia article Chinese character classification gives a pretty good description of this. --103.31.5.230 16:25, 28 July 2016 (UTC)

Does anyone know what the emoticon part is trying to say? 108.162.215.170 16:59, 20 July 2016 (UTC)--

- A loose translation would be "Yes". 162.158.255.106 18:19, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

- 👍=Correct 👏=Bravo/Congratulations 😊=I'm glad you get it --162.158.92.207 18:54, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

- Seems pretty unambiguous to me: "Hitchhikers will bitch-slap you and laugh." 108.162.221.98 02:37, 24 July 2016 (UTC)

- Wat. 162.158.135.52 12:03, 28 July 2016 (UTC)

- Seems pretty unambiguous to me: "Hitchhikers will bitch-slap you and laugh." 108.162.221.98 02:37, 24 July 2016 (UTC)

This comic was posted 3 days after the "World Emoji Day" (July 17) created by Emojipedia founder Jeremy Burge in 2014. The date July 17 appears in the calendar emoji used by Apple, but other tech companies use different dates in their version of this emoji. --162.158.92.207 17:30, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

"Emojish" could be a good replacement for English which suffers from highly nonphonemic orthography and is a pain in the 🍑💨 to wright corecttly. 😊 --162.158.92.207 17:57, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

I lost it at the end of the title text. My friend and I say wat to each other all the time. 108.162.215.144 18:13, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

When I saw the emoji, I realized that I understand them without having a spoken or written language equivalence. We are so conditioned to say "what is it trying to say?" and expecting a language equivalent. But that does not have to be the case. It made me wonder if very early humans using pictographs for communication automatically had language equivalents, or could they think by mentally visualizing the pictograph without translating everything to words. If so, could we train ourselves to imagine emoji instead of words. They clearly communicate something that need not be verbal. Rtanenbaum (talk) 18:59, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

I count 52 Spanish forms of "andar": ando andas anda andamos andáis andan andaba andabas andábamos andabais andaban anduve anduviste anduvo anduvimos anduvisteis anduvieron andaría andarías andaríamos andaríais andarían andaré andarás andará andaremos andaréis andarán anduviera anduviese anduvieras anduvieses anduviéramos anduviésemos anduvierais anduvieseis anduvieran anduviesen ande andes andemos andéis anden anduviere anduvieres anduviéremos anduviereis anduvieren andar andando andado andad. 108.162.219.12 20:13, 20 July 2016 (UTC)

First person singualar "I" is a strange mix. It uses a verb not listed in that chart "am", uses the plural form "have" for present tense, and the singular form "was" for past tense. Tahg (talk) 01:32, 21 July 2016 (UTC)

- It also uses "were" for subjunctive ("If I were you..." // "If I were walking to the park right now instead of being on the computer...")108.162.221.98 13:19, 21 July 2016 (UTC)

Why didn't Randall not use MOAR as a substitute for MORE? 😞😞😞 --Björn -- Windowsfreak (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

The article says that Japanese Kanji (which uses Chinese characters) is uninflected. This is based on a confusion. Japanese itself is highly inflected, with grammatical markers that are usually expressed using either Katakana or Hirigana syllabaries. The Kanji themselves are used for many words but are embedded in sentences that use both Kanji and one or both of the syllabaries. Both nouns and verbs are inflected. There is no such language as "Japanese Kanji" so this is just wrong. I will delete the corresponding clause in the main article. Billjefferys (talk) 12:35, 21 July 2016 (UTC)

The chart lists active and passive forms, many using the helper word "have." However, most writing advice, software, or lessons guide writers into only using active voice and to avoid using the perfect or progressive. Does this mean Modern writing stylists are actively trying to remove the inflections from English while ironically decrying the increase in emoji or LOLspeak that Randall says is the natural result of that removal? 199.27.128.105 21:44, 25 July 2016 (UTC)Fred

Any good reason inflections and pictographs can't occur together? Te ❤️o. Si me ❤️abis, 😁abo. Promethean (talk) 05:03, 3 September 2017 (UTC)

I hate to disagree with Randall on anything ever, but the English inflections came from German. A quick look at Old English verb conjugation shows that it's quite similar to modern German. Latin didn't really start to affect English until the Norman Invasion, after which the church wrote Latin and the government wrote French. Since English wasn't written for over a century, most endings were dropped but none were added. --Jim ocoee (talk) 08:12, 30 June 2021 (UTC)

- English inflection didn't "come from" German, which didn't exist when English split from the other Germanic languages. It was present from proto-Germanic, the ancestor language of Old Norse, Old English, Old Gothic, etc. I believe you meant that English didn't get its inflections from Latin, which is quite true, but Randall and this article never said that it did.Nitpicking (talk) 13:54, 6 February 2022 (UTC)