2094: Short Selling

| Short Selling |

Title text: "I'm selling all my analogies at auction tomorrow, and that witch over there will give you 20 beans if you promise on pain of death to win them for her." "What if SEVERAL people promised witches they'd win, creating some kind of a ... squeeze? Gosh, you could make a lot of–" "Don't be silly! That probably never happens." |

Explanation[edit]

Shorting stocks (short selling stocks) is a stock market practice, generally engaged in by those who expect a particular stock to fall in value. Essentially, rather than buying or selling a stock, one party sells a contract to deliver a stock within a certain period of time, at a price based on the current stock value. If the stock goes down in value, that person can then purchase stock to fulfill the contract at a lower price, thus making a profit. The risk is that, if the value of the stock goes up (possibly by large amounts), the seller then must pay that higher price to fulfill the contract.

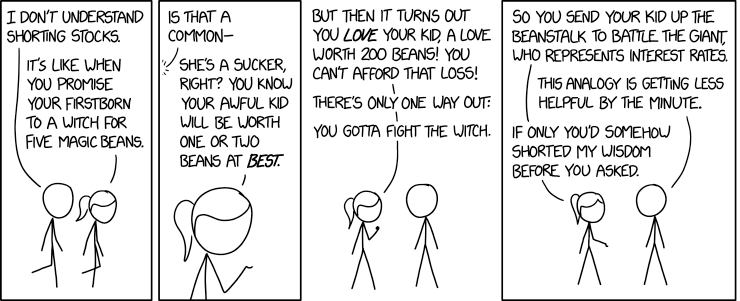

Because short-selling is somewhat more convoluted than the simplest form of investing (which is to buy stocks and hope they go up in value), new investors don't always understand how it works. In this strip, Cueball asks Ponytail to explain shorting stocks. Ponytail starts out with a fairy tale story that falls apart almost before she even starts.

The analogy begins with a somewhat common fairy tale trope of a childless person promising their firstborn child to a witch. This is vaguely similar to short-selling, in that a person is receiving payment in exchange for something they don't yet have, but isn't a really helpful comparison, for a number of reasons. Ponytail then posits that the person turns out to love their child, and value them far more than what they were paid. Once again, that's vaguely similar to short-selling a stock, and then having it go up in value, but is a very bizarre way to demonstrate the notion. In addition to being grotesque, placing a monetary value on your love for your child doesn't reflect how an actual market works (your child is likely worth more to you than to anyone else).

The analogy then goes totally off the rails, telling Cueball that he needs to send his child "up the beanstalk to battle the giant", both of which are completely new elements in the story, and the only justification is that the giant somehow "represents interest rates". Even if that analogy could be justified, it's convoluted and non-intuitive enough that it's not remotely helpful in promoting understanding.

Cueball comments that the analogy is rapidly losing its value to him. Ponytail fires back with the comment that he should have "somehow" shorted her advice before asking for it. This is the essence of short-selling: if something loses value, then someone who shorted it would make a profit. Of course, there is no market for shorting advice, and the value that advice has to Cueball doesn't translate into actual market value. Ponytail seems to be simply mocking Cueball that there's nothing he can do about her advice being useless.

Her story appears to be based on plot elements of multiple fairy tales. It begins by mixing up the story of Rapunzel with Jack and the Beanstalk.

In one version of Rapunzel a father breaks into a witch's garden to steal the Rapunzel plant for his pregnant wife. The Witch catches him and agrees to let him go and not punish him in exchange for the child.

In one version of the "Jack and the Beanstalk" fairy tale story, Jack sells a cow for magic beans. His mother, thinking the beans are fake, is angry with Jack. Jack plants the beans and a magic beanstalk grows up into the clouds. Jack climbs the beanstalk and explores the land above the clouds. He finds the home of a cruel giant and proceeds to steal from the giant. The giant discovers the theft and chases Jack back down the beanstalk. Jack reaches the bottom of the beanstalk first and cuts the beanstalk down. The giant falls to his death, and Jack uses his stolen wealth to take care of himself and his mother.

The combination of the two stories is similar to the story from the musical "Into the Woods," in which a father sneaks into the Witch's garden to steal vegetables, then trades his soon to be born child for the vegetables, but also steals beans in the process.

The title text is actually the most useful part of this comic when it comes to investment advice. It posits a reality in which there actually was a market for advice, and demonstrates how short-selling would work in such a case. The witch (the broker) is offering the father (short seller) 20 magic beans now if the father/short seller buys all of the analogies (stocks) later. If the father believes he can buy the advice for less than 20 beans (because it becomes "less helpful by the minute"), that would seem like a winning trade. But then a risk is brought up: what if multiple witches/stock brokers make the same deal with multiple fathers/brokers? Since every father/seller now needs to buy the same analogies/stocks, a bidding war erupts and it's impossible to please all the witches. The "winner" pays a much higher price than expected, hence losing money on the deal, and the losers wind up either dead or enslaved (bankrupt). In the stock market the corresponding phenomenon is known as a short squeeze, hence Cueball's comment. Ponytail's replies "that probably never happens", which is almost certainly intended as false reassurance. It certainly does happen in real life, and ignoring such risks is a mark of an unprepared investor.

Transcript[edit]

- [Cueball and Ponytail are walking together, talking.]

- Cueball: I don't understand shorting stocks.

- Ponytail: It's like when you promise your firstborn to a witch for five magic beans.

- [Ponytail close up]

- Cueball (off-panel): Is that a common–

- Ponytail: She's a sucker, right? You know your awful kid will be worth one or two beans at best.

- [Ponytail and Cueball stopped, facing each other]

- Ponytail: But then it turns out you love your kid, a love worth 200 beans! You can't afford that loss!

- Ponytail: There's only one way out:

- Ponytail: You gotta fight the witch.

- [Ponytail and Cueball stopped, facing each other]

- Ponytail: So you send your kid up the beanstalk to battle the giant, who represents interest rates.

- Cueball: This analogy is getting less helpful by the minute.

- Ponytail: If only you'd somehow shorted my wisdom before you asked.

Discussion

It's like he's doing that on purpose to make it extra difficult for this site to explain his comics. :D I at least understood nothing. Fabian42 (talk) 16:19, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- @Fabian42, Ha! Yes, I'm in the same boat with you, It's almost like he follows this formula: 1. Pick a topic that very few understand. 2. Make an analogy that is more complicated than a straightforward explanation. 3. Profit.

- I've been reading a page on short selling, it's like they're speaking a foreign language. 172.69.70.47 16:42, 4 January 2019 (UTC) sam

- It makes sense from what I remember from economics in high school: you buy stocks in advance for significantly above asking price hoping they gain more value before the deal happens, so let's say 1 share of company X is worth 20$ right now. Now I can offer you a contract that I'll buy this share from you for 50$, but on the condition that the deal happens in a week. If the value of the company stays the same, I make a loss; but if the value rises within that week and one share is suddenly worth, let's say 2000$, I make an immense profit. (divide each value I gave by ten and you have the bean/witch/child analogy from the comic) It's basically gambling on the hope that the value of stock rises. --172.68.50.118 17:24, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- How are stock markets even still legal? This is insane! Fabian42 (talk) 17:42, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- what would be insane would be trying to outlaw stock markets. They’ve been around for hundreds of years; business people are going to find ways to trade. -- 172.68.65.6 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- If you think short-selling shouldn't be legal, you should look into Quantitative easing and Fractional-reserve banking. -- Hkmaly (talk) 18:16, 5 January 2019 (UTC)

- What you (and Ponytail, FWIW, given how muddled the analogy is of course) describe sounds more like selling put options than short selling. Stannius (talk) 19:10, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- You don't actually buy the shares beforehand. What happens is that if you think a stock is overvalued, you can borrow some shares of it from a broker and sell them at the current price. You then owe the broker those shares that you hope to repay by purchasing it at a lower price in the future, but if the stock instead goes up, you may be squeezed into shelling out money for the higher price. Why is this useful to the market? I recommend reading The Blind Side for a good example. Market prices tell us a lot of information about what a great deal of people think about the value of things. This information is a lot more accurate when those who think something is overvalued have as much of a say as those who think it's undervalued. Asset bubbles would happen a lot more often otherwise. PerfectlyGoodInk (talk) 18:50, 7 January 2019 (UTC)

- How are stock markets even still legal? This is insane! Fabian42 (talk) 17:42, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- It is not that hard to understand. Imagine you own 100 apple-shares and do not plan to sell them for the near future. You lend me these 100-shares for 2 weeks. I sell the 100 shares immediately. Now I have 2 weeks to re-buy them. If I’m lucky the price for these 100 shares will decrease somewhen during this 2 weeks. Imaging that I sold the shares for 200$ each, and could re-buy them for 170$: Then I made 30*100$=3000$. Of course you will get a fee for the borrowing. The 3000$-fee are my profit.

- The risk here is of course that the shares could increase in price during the 2 weeks – then I would be forced to rebuy them for more that I got AND have to pay you the fee. That’s the reason shorts are more dangerous then longs. --DaB. (talk) 17:36, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- You sell something that you borrowed? Why would that be allowed? It's not yours! And what happens if you can't buy it back? Fabian42 (talk) 17:42, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- It’s totally legal to sell something that you borrow. If I could not buy it back you and I will have a problem – so you do this kind of business only with people/firms with money.

- But to show you something that IS crazy, there is also Naked short selling – that’s like short-selling on speed. With this kind of short-selling, I do not borrow anything. It works in this way: Today I sell you 100 apple-shares, which I do not have, for 200$. You have to pay me immediately, so I collect 100*200$=20,000$. I will deliver these shares when I have to, which is 1 or 2 days from now (depending on the market-place). So if I’m lucky and the price drops the next 1 or 2 days, then I make profit. For example if the apple-shares decrease again to 170$, then I make 100*(200$-170$)=3000$ profit. Some countries (but not the US AFAIK) forbid these kind of short-selling, after the last financial crisis. --DaB. (talk) 20:37, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- Shares are fungible, like money, so it makes perfect sense. If I borrow a £10 note from you, there's no expectation that I'll keep it safe and return the exact same £10 note to you; I'm probably borrowing it to spend it. But you don't care as long as I return £10 to you at the end of the loan. Every pound is interchangeable with every other pound; and it's the same with shares of a given type. --162.158.155.116 16:14, 5 January 2019 (UTC)

- You sell something that you borrowed? Why would that be allowed? It's not yours! And what happens if you can't buy it back? Fabian42 (talk) 17:42, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- It makes sense from what I remember from economics in high school: you buy stocks in advance for significantly above asking price hoping they gain more value before the deal happens, so let's say 1 share of company X is worth 20$ right now. Now I can offer you a contract that I'll buy this share from you for 50$, but on the condition that the deal happens in a week. If the value of the company stays the same, I make a loss; but if the value rises within that week and one share is suddenly worth, let's say 2000$, I make an immense profit. (divide each value I gave by ten and you have the bean/witch/child analogy from the comic) It's basically gambling on the hope that the value of stock rises. --172.68.50.118 17:24, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

Short selling doesn't seem all that complicated. It's the night before black friday, and your friend has [hot new amazing toy] that they picked up a few months ago before it got popular. You ask if you can borrow it for a week. Then you go out the next morning and scalp it to a frustrated parent that is desperate to get it for their kid but the store is sold out. A week goes by, and you head to the store and pick one up now that they are back in stock and on sale, and give it back to your friend. Your friend has a toy, even if it's not exactly the same one, and the price difference between what you sold it for and what you paid for the new one gave you a bit of holiday spending money. The danger is if the toy doesn't get back in stock or the price goes up due to demand and you have to buy it for more than you sold it. Andyd273 (talk) 17:45, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

It seems like the title text implies there are multiple witches involved. This should perhaps be mentioned in the explanation. 108.162.241.202 18:04, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

- I’m confused... which which is which?172.68.65.6 05:20, 5 January 2019 (UTC)

- I believe the pun is related to how multiple people promising to win the auction is going to drive prices higher. If this is somehow related to some story with multiple witches, it's beyond my knowledge. It's entirely possible the witches are there only to connect the title text with the comic dialog. Also, I find it interesting that Cueball didn't actually ask Ponytail for her wisdom - he only made a comment which she then answered. Ianrbibtitlht (talk) 19:36, 4 January 2019 (UTC)

someone takes !-> they believe !-> their strategy; 1 != 2; will (optative) -> shall (future); he -> who; witches -> witch's; would (desiderative) -> should (conditional) Lysdexia (talk) 02:38, 5 January 2019 (UTC)

What about that word "squeeze" in the title text? We need an explanation. There is a page Short_squeeze on Wikipedia which is surely relevant, but I don't understand it enough to explain it here. 141.101.98.178 12:41, 6 January 2019 (UTC)

- Off the top of my head, when a short seller borrows shares and sells them, they essentially have a margin loan. The cash from the short sale is their collateral, which has a fixed value. The value of their loan fluctuates with the price of the stock that they sold. The broker wants to make sure they get paid, so if the stock price goes too high, the broker can make a margin call to the short seller, telling them they need to pay back the borrowed shares before its stock price gets any higher. This forces them to buy the stock at the higher price for a loss. Since buying a stock increases the demand and thus creates an upward pressure on the price (all else remaining equal), one tactic for those holding the stock and wishing for the price to go up is to buy a bunch more shares to drive up the price to the point where this happens, betting on that the price will then go up even more. This tactic is called a short squeeze.PerfectlyGoodInk (talk) 19:04, 7 January 2019 (UTC)

There is an element of fighting the Witch - when a short seller is set to lose they do all they can to undermine the company. Elon vs. Short Sellers as case in point.

Why assume that the first born child is not yet born? I've had one of those for decades. How many magic beans am I offered? J Milstein (talk) 16:08, 7 January 2019 (UTC)

- Because a child already born has a more settled value. in Ponytail's story the seller is assuming they'll have a rotten 2 bean kid, and basically betting the witch that the kid will be worth 5 beans tops. In your case a trade would be more like a normal sale than a "short sale".162.158.187.25 19:11, 7 January 2019 (UTC)

Since my kid is already born I have more information and can sell the kid I know to be rotten to a witch who does not have this information. This is like selling a used car. The unborn child is like a new car. In any case, the market in used kids is just as likely to fluctuate, maybe more, as the market in newborns. J Milstein (talk) 19:37, 7 January 2019 (UTC)

I actually read a similar fairy tail once, a mermaid asks a fisherman if he would trade his son for good catches. Saying "yes I would, but I do not have a son." the fisherman looks back. The mermaid says that she would come for his oldest son when he is twenty years or something, and giving him good catches. The father warns his son to leave when the son is almost of age, starting him on an journey, but that is another tale. 141.101.105.6 18:24, 17 January 2019 (UTC)