Difference between revisions of "2545: Bayes' Theorem"

(→Explanation) |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

|| Total || 1% || 99% || 100% | || Total || 1% || 99% || 100% | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | For example, if a test has a 100% sensitivity (all those | + | For example, if a test has a 100% sensitivity (all those affected receive a positive result) and a 99% specificity (1% of the unaffected also receive a positive result), the interpretation of a positive test depends on the prevalence of the disease in the population. In the example case, the prevalence is 0.1%, so that when the test result is positive (left column) the subject is unaffected nine time out of ten. Although this would be a very performant test, given the relative prevalences involved it will produce overwhelmingly false positives among all positive results. (But, in this example, all those told they are not in danger — almost a hundred times more individuals than test positive — are correctly notified.) |

| − | For this same example, the Bayesian formula gives : P( Affected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Affected ) * P( Affected ) / P( Positive ) = 100% * 0.1% / 1% = 10% and P( Unaffected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Unaffected ) * P( Unaffected ) / P( Positive ) = 0.9009% * 99.9% / 1% = 90% | + | For this same example, the Bayesian formula gives : |

| + | P( Affected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Affected ) * P( Affected ) / P( Positive ) = 100% * 0.1% / 1% = 10% | ||

| + | and P( Unaffected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Unaffected ) * P( Unaffected ) / P( Positive ) = 0.9009% * 99.9% / 1% = 90% | ||

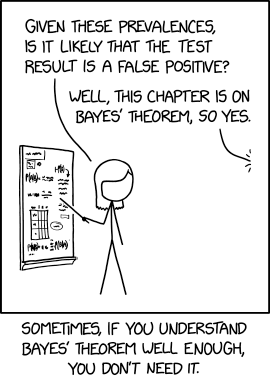

In this comic, a teacher is presenting a problem which the students are supposed to use Bayes' theorem to solve. However, the off-panel student knows that they are studying Bayes' theorem, so they use that prior knowledge to guess the usual answer to such problems. The punch line is the caption - The student doesn't need to do the calculation because they're familiar with questions involving Bayes' theorem and how they often present the counter intuitive result to illustrate the importance of prevalence to the calculation. | In this comic, a teacher is presenting a problem which the students are supposed to use Bayes' theorem to solve. However, the off-panel student knows that they are studying Bayes' theorem, so they use that prior knowledge to guess the usual answer to such problems. The punch line is the caption - The student doesn't need to do the calculation because they're familiar with questions involving Bayes' theorem and how they often present the counter intuitive result to illustrate the importance of prevalence to the calculation. | ||

Revision as of 03:42, 24 November 2021

| Bayes' Theorem |

Title text: P((B|A)|(A|B)) represents the probability that you'll mix up the order of the terms when using Bayesian notation. |

Explanation

| This is one of 62 incomplete explanations: Created by P(d/dx x^x|P(d/dx|x^x))) - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

Bayes' theorem describes the probability of an event, given knowledge of conditions related to the event. It is typically used to update the probability that a starting condition occurred, given an outcome. This can reveal unintuitive results when the probability involved is very small. For example, when testing a large number of people for a rare disease, even a fairly accurate test will produce more false positives than the number of people actually afflicted with the disease, and hence a positive result is more likely to be false than true.

| Tested positive | Tested negative | Total | |

| Affected | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Unaffected | 0.9% | 99% | 99.9% |

| Total | 1% | 99% | 100% |

For example, if a test has a 100% sensitivity (all those affected receive a positive result) and a 99% specificity (1% of the unaffected also receive a positive result), the interpretation of a positive test depends on the prevalence of the disease in the population. In the example case, the prevalence is 0.1%, so that when the test result is positive (left column) the subject is unaffected nine time out of ten. Although this would be a very performant test, given the relative prevalences involved it will produce overwhelmingly false positives among all positive results. (But, in this example, all those told they are not in danger — almost a hundred times more individuals than test positive — are correctly notified.)

For this same example, the Bayesian formula gives : P( Affected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Affected ) * P( Affected ) / P( Positive ) = 100% * 0.1% / 1% = 10% and P( Unaffected | Positive ) = P( Positive | Unaffected ) * P( Unaffected ) / P( Positive ) = 0.9009% * 99.9% / 1% = 90%

In this comic, a teacher is presenting a problem which the students are supposed to use Bayes' theorem to solve. However, the off-panel student knows that they are studying Bayes' theorem, so they use that prior knowledge to guess the usual answer to such problems. The punch line is the caption - The student doesn't need to do the calculation because they're familiar with questions involving Bayes' theorem and how they often present the counter intuitive result to illustrate the importance of prevalence to the calculation.

There is perhaps also a self-referential situation here where the student has updated their prior probabilities a number of times for whether the answer was "Yes" to a question involving Bayes' Theorem. If their method of answering "Yes" to every such question has succeeded every time before then by Bayes' theorem they will have a lot of justification to continue to do until they start getting it wrong. The prevalence of Bayes Theorem questions that require the answer "No" might be small enough that this doesn't happen in any small number of times and so they learn nothing of the false-positive rate until that point in time. This could be interpreted as a criticism of Bayesian Statistics which may treat a judgement as well justified (e.g. getting the question right) despite lacking a clear understanding of mechanism (e.g. basing your answer to the question on the numbers provided).

The title text refers to the mathematical definition of Bayes' theorem: P(A | B) = P(B|A) * P(A) / P(B). Here, P(A|B) represents the probability of some event A occurring, given that B has occurred. This is often referred to as "the probability of A given B". It can be hard to remember if P(A|B) means probability of A given B, or if it's B given A, especially when talking about the probability of an earlier cause given a later effect. Randall's joke is based on this difficulty. Here P((B|A)|(A|B)) is meant to be read as the probability that you write (B|A) given that the correct expression is (A|B), which makes it the probability that you got the order of the notation mixed up.

Transcript

- [Miss Lenhart is pointing with a pointer, held in her right hand, to a white-board with tables, what looks like formulae and lots of other unreadable text. She looks toward her off-panel class, from where a voice replies to her question.]

- Miss Lenhart: Given these prevalences, is it likely that the test result is a false positive?

- Off-panel voice: Well, this chapter is on Bayes' Theorem, so yes.

- [Caption below the panel]:

- Sometimes, if you understand Bayes' Theorem well enough, you don't need it.

Trivia

- When this comic came out, the title text was only "P((B", and the comic itself linked to A) or A) (depending on where the comic was viewed from) and the "Black Lives Matter" image in the header was replaced by "(A", but this was quickly corrected.

- See this archived version.

- It turns out that it is the notation that messes with the home page as it also messes with this wiki.

- In this version of this page, the correct title text has been entered, but it still looked the same so everything from behind the first "|" fails to show.

- Now this has been fixed using the <nowiki> format.

- Seems like Randall made an exploit on himself like Mrs. Roberts did in 327: Exploits of a Mom.

- This is extra funny since Blondie, is both sometimes used for Mrs Roberts and for Miss Lenhart from this comic.

Discussion

I don't know if the latest (nearly!) global change back to "affected" in the example was intentional or just a cut'n'paste of historical wordings whilst making other tweaks, but I'm not going to go through and change to "infected" a third time (first time, collided with an edit conflict, and so cancelled and worked again on that, albeit with at least one new typo). Yes, in general, being affected or not is correct, but with "affect/effect" confusion (for some) and elsewhere described as "afflicted with" and (still in at least one place) "infected" the example works as well or even better with infections rather than affectations. I was also tempted to change "performant" as not everyone will know exactly what it means, but was stuck for a good substitute ("efficacious" is close, but probably doesn't help a great deal). 172.70.90.211 09:50, 23 November 2021 (UTC)

- I would expect the <1-in-1000 sorts of numbers relevant to the comic to apply to genetic conditions and cancer, not to infections. We don't screen wide swathes of asymptomatic population for infections. Even now with all the testing for COVID-19, the positivity rate is above 1%. -- [[User:{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]] ([[User talk:{{{1}}}|talk]]) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- I'd say "afflicted" throughout would be best, of the suggestions given. Avoid "sufferer/ing" (is benign, or they're a carrier only?) or similar. "Susceptible" might work if you bake that into a minor scenario rewrite.

- But "affected" is vague... Relatives are "affected" if they change their routine to care for an ill person, however negative they'd test.

- (I also instinctively avoid effect/affect because of the 'P((effect|affect)|(effect|affect))' affect/effect... ;) But not a good reason, just nice to hear it's not only me trying to dodge this in everyday writing!) 172.70.162.215 08:02, 24 November 2021 (UTC)

- This is why I proposed ӕffect as a compromise position - but mostly to annoy a friend who studies old english.162.158.91.50 13:00, 25 November 2021 (UTC)

- What was thér response? 172.70.85.227 10:26, 24 November 2021 (UTC)

- They seemed unrædy to hear it 162.158.91.50 13:00, 25 November 2021 (UTC)

- This is why I proposed ӕffect as a compromise position - but mostly to annoy a friend who studies old english.162.158.91.50 13:00, 25 November 2021 (UTC)

- How about "Has condition" and "Doesn't have condition"? It's not too linguistically confusing and aligns with normal parlance -- "I have a cold". The table isn't trying to avoid a multi-word solution, as the headers are two-word phrases. 172.69.68.158 23:46, 10 January 2022 (UTC)

This is the second comic to reference Bayes' Theorem: https://xkcd.com/1236/. Is that worth mentioning in the explanation? I'm a newbie!172.70.34.191 21:32, 23 November 2021 (UTC)

Actually, I forgot this one too: https://xkcd.com/1132/ 172.70.34.191 21:35, 23 November 2021 (UTC)