1908: Credit Card Rewards

| Credit Card Rewards |

Title text: I should make a list of all the things I could be trying to optimize, prioritized by ... well, I guess there are a few different variables I could use. I'll create a spreadsheet ... |

Explanation

A credit card, at its most basic form, is a loan contract to an individual from a bank. Like all contracts, the bank will offer several different types in an attempt to appeal to a large number of individuals. Unlike traditional loans which focus on a single item (car, house, boat, etc), a credit card is an unsecured loan geared towards daily and weekly transactions. Because these transactions cover a wide variety of items, credit cards can be further tweaked towards offering benefits in certain areas. For example, gas purchases, or even gas purchases through a single retail chain, can offer higher rewards on one type of plan vs. other plans.

These benefits, typically called rewards, have several different options. "Cash back" is a reward where the individual is given money back when they make a purchase that follows certain rules spelled out in the contract. "No interest" is a reward where the individual is not charged interest on their purchases if they pay the loaned money back within a specified amount of time. "Points" are similar to the cash back program, but are typically reserved towards purchasing a single large item or plan. Points towards a vacation is a popular option. Besides these three types of rewards, the number of actual rewards to pick from are limited only by the creativity and fiscal limitations of the issuing bank.

Cueball is trying to choose the optimal credit card program that will result in the biggest savings for his typical income and spending patterns. He will need to trade off the value of any benefits against the cost of any fees and interest charges that would be incurred. This could become quite complex if he is prepared to consider taking out multiple cards to access the various benefits they offer, and in order to get the best outcome he may need to regularly shift funds from one card to another to make use of introductory or short-term offers. On top of all this, the incentives on offer may change his spending behaviour, which would further impact the calculation.

He realizes that there is a cost of him spending time on optimizing his choice, so he wants to limit the time spent doing the optimizing so that it doesn't outweigh the maximum advantage he might gain from choosing the best deal. Finding a definite answer to the time at which he should stop his optimization efforts is hard, if not impossible, because the fact that he cannot complete them means that he probably cannot know for certain what the maximum advantage would be; he will have to rely on a probabilistic solution instead. To further complicate things, he will need to factor in the cost of the time spent solving the problem of how long to spend on optimizing (and, presumably, the time spent solving that problem, and so on infinitely).

Hairy challenges a hidden assumption that Cueball's time has significant value, which would imply that if he wasn't worrying about this problem he would be doing something more productive. Cueball's obsession with optimization is lame enough to suggest that he does not actually have any more worthwhile interests to pursue. His response that he "could be failing to optimize so many better things!" rather proves Hairy's point, and suggests that Cueball is aware of both the big flaw in his reasoning and the fact that, when he attempts to optimize things, it seldom really helps his situation.

The title text further expands the idea. Cueball wants to work out which optimization problems he could most productively work on first. However, his proposed idea of creating a spreadsheet to calculate this may well end up costing more in time than the benefit he would gain from working on them in priority order (particularly since, on this evidence, the potential gains from each problem are marginal at best). Furthermore, if the 'several variables' he needs to consider lead to the kind of complexity seen in the credit card problem, a spreadsheet may not be the best tool for the kind of calculations he needs to perform.

Transcript

| This is one of 34 incomplete transcripts: Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

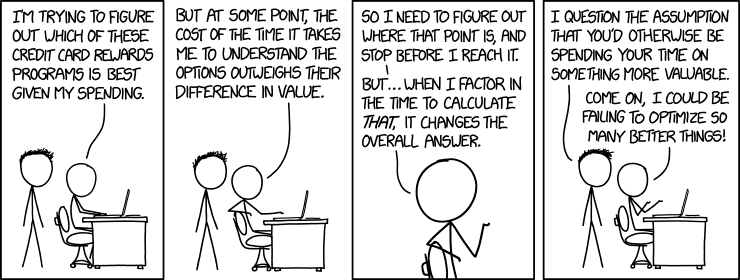

- [Cueball sits at a desk and is on his laptop. Hairy stands behind him.]

- Cueball: I'm trying to figure out which of these credit card rewards programs is best given my spending.

- [Cueball leans backwards in a frameless panel.]

- Cueball: But at some point, the cost of the time it takes me to understand the options outweighs their difference in value.

- [Close-up of Cueball's head and torso.]

- Cueball: So I need to figure out where that point is, and stop before I reach it.

- Cueball: But... when I factor in the time to calculate THAT, it changes the overall answer.

- [Cueball has his arms outstretched.]

- Hairy: I question the assumption that you'd otherwise be spending your time on something more valuable.

- Cueball: Come on, I could be failing to optimize so many better things!

Discussion

Does Randall realize this goes completely against the "Working" comic (https://xkcd.com/951/)? I wonder if he's changed his outlook or if he's just inconsistent :P

- I read it as if the character likes doing this, and wouldn't be doing anything more fun otherwise. So if it is a game to you, sure waste your time, but if you are doing something you don't particularly like and waste more time than you save in money, you are just being stupid.162.158.202.28 22:43, 29 October 2017 (UTC)

- There's also the fact that in "Working" the additional work was required every time, and so each additional penny saved comes from additional work. Here, this is about doing the work once and getting the outcome several times. This is actually pretty consistent with someone who is into programming - where in theory you do more work once to save time on each occurence of a repeted task. Now the fact that even "optimizing once and for all" isn't a sure outcome is discussed in https://xkcd.com/1319/ . 162.158.92.136 11:24, 30 October 2017 (UTC)

- I've often used this reasoning myself, actually. First example to mind is renaming multiple files (like episodes of a TV show). I COULD rename them one by one according to my naming scheme, but often I put a little extra work into having Excel figure out my scheme and renaming them programmatically, then rename them all in under a second. The time I spent is more than how long renaming a file or two would have been, but less time than if I had renamed them all. :) NiceGuy1 (talk) 04:38, 31 October 2017 (UTC)

- Actually I find the point of view here is roughly identical to Working... In that one he has successfully determined that the extra time isn't worth it in that particular case, while here he's trying to find a balance between the extra time spent and the rewards of his analysis. :) NiceGuy1 (talk) 04:38, 31 October 2017 (UTC)

- I don't it goes against 951, essentially he's trying to stop before he's spent 9 minutes to save a dollar (and hairy is questioning that he would have otherwise spent that 9 minutes earning more than a dollar) 108.162.216.136 01:17, 28 October 2017 (UTC)

This reminds me of Hofstadter's law // See also #1658 and this Explain xkcd for #1658 18:26, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

How did he miss the circular reference error? (unsigned comment from 108.162.219.94)

This is similar to comic 1205 (Worth the time), except that it's just a one-time event and just thinking about the table makes it worse. For example the top right cell of that table could just say "none, because it took you longer to search for and apply this chart). Fabian42 (talk) 09:36, 30 October 2017 (UTC)

There's also 1445 (Efficiency), in which Randall confesses this search to optimize tasks killing his effeiciency is a personal problem for him. 162.158.69.241 14:30, 30 October 2017 (UTC)

Simple, use an infinite summation to figure out exactly. That's right, Jacky720 just signed this (talk | contribs) 18:41, 15 April 2018 (UTC)