2214: Chemistry Nobel

| Chemistry Nobel |

Title text: Most chemists thought the lanthanides and actinides could be inserted in the sixth and seventh rows, but no, they're just floating down at the bottom with lots more undiscovered elements all around them. |

Explanation

| This is one of 62 incomplete explanations: Created by THE SOCIETY OF ANNOYING MENDELEEV. Standard wait time in progress. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

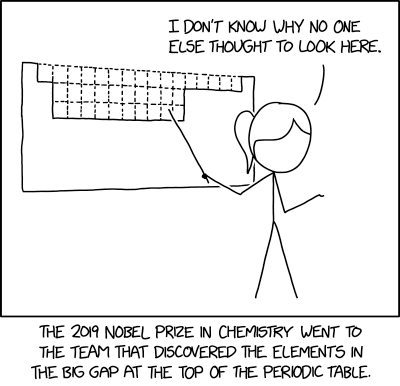

This comic shows a misconception being made: that the empty space at the top of the periodic table represents undiscovered elements, akin to some existing elements having been discovered unfilled gaps in the table. This is an absurdity; despite this, the team shown has won the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. In real life the prize was awarded to John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham, and Akira Yoshino for their work in the development of lithium-ion batteries; it was announced on October 9, just a few days before this comic was published and may have inspired it.

In reality, the gap is purely a result of human bookkeeping, and real life elements are not beholden to the way we place tiles on a table. The table, gap included, was a deliberate design created by Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev to represent the repeating properties of the elements as the elements became more massive. Simply put, each row of the periodic table collects together elements with the same number of electron shells. Lower shells have fewer electrons, so the upper rows have fewer elements in them. Meanwhile, as the rows get longer, the "extra" elements are added in the middle of the row rather than at one end because of the way the columns are organized (grouping together elements based on certain characteristics). Hence, earlier rows are shown with a gap in the middle.

The title text claims that the lanthanides and actinides are distinct from the elements in the sixth and seventh rows; in actuality, they are only ever shown separately for convenience. (When expanded into its 32 column form, the sixth and seventh rows are awkwardly wide, so placing the lanthanides and actinides in a separate block below the table is the usual solution.)

Among themselves the lanthanides and actinides are (due to the order the orbitals are filled) chemically very similar. The period system has its name from the periodic change of elements by putting similar elements in the same column, but keeping the order. With heavier elements and shells further away, more and more elements fit into each shell (2*n²), so the period (after which the element properties repeat) also increases. Some orbitals in the shells are chemically relevant, some not.

In addition, it says that there are many more elements around it. Heavier elements could certainly show up at the bottom, but again, the lanthanides and actinides would not be among them.

Transcript

| This is one of 41 incomplete transcripts. Please help by editing it! |

- [Ponytail holds a pointer and stands in front of an image of the periodic table of the elements, with the “empty” sections within the top rows filled with dotted boxes. Ponytail points to this area.]

- Ponytail: I don't know why no one else thought to look here.

- [Caption below the panel]:

- The 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to the team that discovered the elements in the big gap at the top of the periodic table.

Discussion

No Discussion yet? REALLY?!!? 162.158.214.82 15:23, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

This may be a reference to SCP-2046. 162.158.146.34 15:40, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

- Or something else. From the beginning, what are the ten radical isotopes? -- Hkmaly (talk) 21:36, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

- From the beginning, the ten radical isotopes are: Tukerium, negative 5. Dangor, negative 17. Lu, negative 31. Kartex, negative 79. Sharbar, negative 101. Muilamium, negative 127. Idaron, negative 173. Simmondsium, negative 211. Mattite, negative 239. Krasnov, negative 307. These are the radical isotopes from the beginning. --[REDACTED], 10/25/2024 04:26

Couldn't this potentially involve exotic isotopes of hydrogen that behave similarly to elements in the same group? --162.158.214.136 16:02, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

Oh gods, I needed this laugh. Have my Chemistry exam on Monday, this does put a smile on my face.

"misconception that the empty space at the top of the periodic table represents undiscovered elements"... [citation needed]. Is that really a thing? Never heard of it. Ralfoide (talk) 16:53, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

- Somehow I did not think about that the entire time I was editing this thing, because I don’t believe it is. I guess I’ll fix it. 172.69.34.56 18:32, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

Some uninvited pedantry (unlike all my other didactic discourse here, which you guys bring on yourselves): Referenced in the comic is not THE periodic table, just a periodic table. And it isn't really objectively scientific. It's better to call it the most popular periodic table. Such tables are a rather ham-handed attempt to explain the patterns of the elements in an "intuitive" (or at least heuristic) way. But the popular one we learn in school is actually far from the best one even in that sense. Check out the alternatives, many of which are more scientifically sound and logical...but aren't as simplistic for the easy-minded, so they haven't caught on. —Kazvorpal (talk) 23:37, 12 October 2019 (UTC)

- Do you mean the one that looks like a candyland board game (Benfey's) or the one that looks like the worst Tetris level ever (Tsimmerman's)? [j/k]... If I had seen that in school, I'd have been too distracted to ever pay attention ;-) Ralfoide (talk) 07:35, 13 October 2019 (UTC)

- A very interesting link. Thanks! Yosei (talk) 12:41, 2 December 2019 (UTC)

Did Mendeleev really design his table to represent the way electrons are arranged in atoms? In 1869, he must have been quite a visionary! Zetfr 09:23, 13 October 2019 (UTC)

- Oh no, he didn't. He did by patterns of their properties. Also by atomic weights, but those were imprecisely known then, also note the isotope paradox problem (e.g. K and Ar must be swapped). The first sorting already guarantess to represent the electronic arrangement to some degree. BTW, lanthanides and actinides need more love. For starters, I PhD'ed on them.

- Actually he was quite the visionary, considering what they didn't know back then. While everybody else was arranging their tables (and there were plenty of them) entirely by atomic weight, he arranged them by both atomic weight on the large scale and chemical valence on the small scale. This clued him in to the changing periods and also enabled him to correct elements out of order by weight. The noble gases hadn't been discovered yet, but when they were, they fit right in as they had a valence of zero. A few decades later Henry Mosely used proton bombardment and X-Ray radiation measurement to determine the electrostatic properties of various elements and found a simple progression that both absolutely vindicated Mendeleev and introduced the concept of Atomic Number. He should have gotten a Nobel prize, but sadly, no prizes were awarded that year because of the war and Mosely himself was killed at the young age of 27 by a bullet with his name on it. Sigh.

172.69.55.22 15:20, 13 October 2019 (UTC)

Clearly these new elements are fractional elements, with elements having - for instance - 1 3/16 protons, etc. 108.162.241.248 21:20, 13 October 2019 (UTC)

Of course, if someone did find a whole bunch of elements there, I'd say that they deserve a Nobel prize. 172.69.63.133 12:37, 14 October 2019 (UTC)

for me, the explanation provided doesn't seem to emphasize why the joke works well enough. shouldn't the explanation more clearly state that the gap between hydrogen and helium is there because the table is grouped based on blocks of elements and electron orbits. the first row only has electrons in the s orbital and none in p, d or f orbitals, and that gaps between hydrogen and helium, for example, could not possibly be filled because there isn’t anything to fill them with. similarly for the 2nd and 3rd row "gaps". this impossibility really begets the humor of a figure pointing at the gap musing "i don't know why no one else thought to look here".

In Russian books on chemistry, elements are numbered, ordered in the same way, yet the table itself is arranged in a different manner: in R20, RO, R2O3, RO2, R2O5, RO3, R2O7, RO4 way. It, however, is done to make both the table + all the extra data on each element rectangular (so it would fit into one A4 sheet).172.68.11.67 05:14, 20 March 2021 (UTC)

A girl in my high school chemistry class seriously thought this. She was trying to argue with the teacher that "There's infinitely many elements, we just haven't discovered them yet. You can't prove 1p and 2d orbitals don't exist just because we haven't seen them." Ironically she was the "religion is the cause of all society's problems" type atheists.

StapleFreeBatteries (talk) 21:45, 5 August 2024 (UTC)

- To be half fair, to her statement (as reported), there's indeed no reason to believe that there aren't an infinite number of elements, just by extending the current table down infinitely (with or without filling in the 'gaps' in the top of it, which add only a finite extra number). Beyond (well beyond?) the lanthinide/actinide full-width it doesn't even need additional shells (unseen, thus not currently featured in the 'wider gap' model, just like La/Ac groups and transitional metals crowbar the upper bits apart, and indeed everything not Group1 or Group8/0 levers H and He apart), but that might happen too – without needing the new (upper) gap to be filled as well. 172.70.91.139 14:57, 6 August 2024 (UTC)

Add comment

Add comment