1071: Exoplanets

- Not to be confused with 786: Exoplanets.

| Exoplanets |

Title text: Planets are turning out to be so common that to show all the planets in our galaxy, this chart would have to be nested in itself—with each planet replaced by a copy of the chart—at least three levels deep. |

- A larger version of this image can be found by clicking the image at xkcd.com - the comic's page can also be accessed by clicking on the comic number above.

Explanation

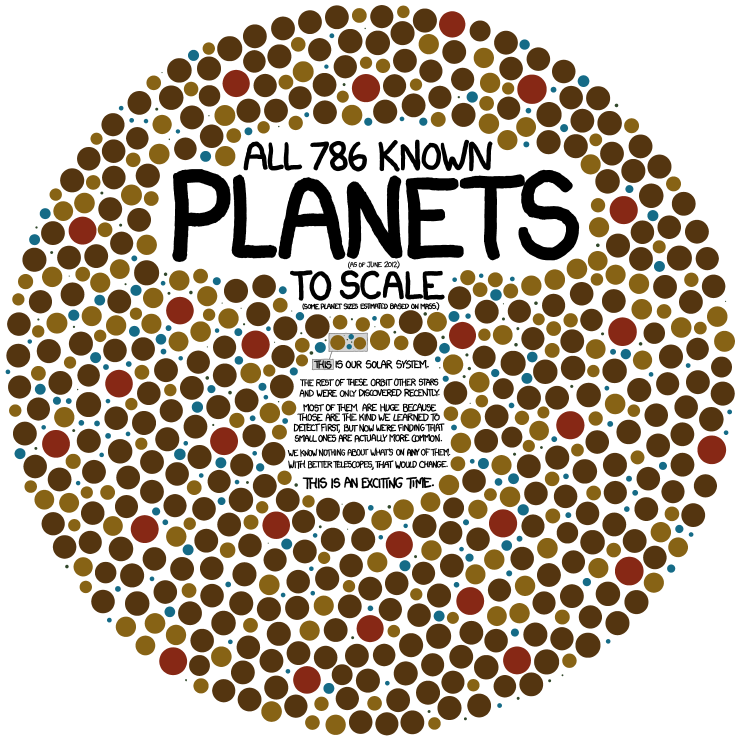

An exoplanet is a planet outside of our solar system, orbiting a different star. 786 planets were known in mid-2012: 778 exoplanets and the rest in our Solar System.

Since then, astronomers have found thousands more. In the comic, our Solar System's eight planets are depicted in the small rectangle above the central text. From this we find that the largest dots (red) and second largest dots (dark brown) indicate planets larger than Jupiter, light brown is roughly Jupiter or Saturn-sized, blue is roughly Uranus or Neptune-sized, and the tiny dots are small terrestrial planets (like Earth).

We only have a few ways of finding exoplanets. Astronomers initially used doppler spectroscopy, which detects minute changes in a star's movement towards or away from us to infer the presence of large gas giants or brown dwarfs. Currently the most successful method is to notice when a star seems to briefly get dimmer on a repeating cycle. This may indicate that a body of matter has passed between that star and us, blocking some of the light. The Kepler space telescope was designed for this purpose, and has made the vast majority of exoplanet discoveries.

Most of Kepler's discoveries are between the sizes of Earth and Neptune, but it's sensitive enough to detect planets smaller than Mercury (if the orbital plane is aligned with us). Kepler is only able to observe relatively close stars in a narrow field of view. The great number of nearby planets implies there should be billions of planets in our galaxy, assuming our local arm is not uniquely abundant.

The title text refers to this by saying that to show them all, each dot on the chart should hold another chart with the same amount of dots; each of these dots should then also have a similar chart, and then do this one more time for a three level deep chart. This chart would have space for 786^4 planets (786*786*786*786 = 382 billion). Our Milky Way contains about 100-400 billion stars. But if the chart were only two levels deep there would "only" be room for 786^3 = 0.5 billion planets.

This comic's design is similar to the Ishihara Color Test, a series of circular pictures made of colored dots, used to detect red-green color blindness. However, Randall's picture probably does not contain a hidden number like it did in 1213: Combination Vision Test.

See also Category:Exoplanets and this list of lists of exoplanets.

Transcript

- [A large diagram of dots, mostly of varying shades of brown and greenish yellow, with a number of smaller blue dots, tiny green dots and some larger red dots. At the top of the circle are five lines of text in very different font size.]

- All 786 known

- planets

- (as of June 2012)

- to scale

- (Some planet sizes estimated based on mass.)

- [Below this text is a small section of 8 planets which are framed in a light gray frame with lighter gray background . It is situated right below the above text with only a few planets in between the text and the frame. These planets include two large yellow, two smaller blue two small green and two tiny green planets. A line goes between this frame to another frame with the first word in the text below, that is in a similar frame. The rest of the text follows to the right and then below this first word covering the central part of the circle from just around the center of the circle and a bit below.]

- This is our solar system.

- The rest of these orbit other stars and were only discovered recently.

- Most of them are huge because those are the kind we learned to detect first, but now we're finding that small ones are actually more common.

- We know nothing about what's on any of them. With better telescopes, that could change.

- This is an exciting time.

Trivia

- This was the first time Randall released a comic with the exact same name as a previous comic, in this case 786: Exoplanets, released on August 30, 2010. Since then, he has done so a few times. When this comic was released, it caused problems on xkcd as the title of the image file (

explanets.png) was the same for the two comics. This was resolved by renaming the old comic's image, adding the year of its release to the title:explanets_2010.png.

- The number of the first comic with this name, 786: Exoplanets, is the same number of planets featured in this comic (786 planets). It isn't clear whether this is a coincidence or Randall purposefully waited for the number of discovered planets to be the same as the old comic's number.

Discussion

Hmm... this comic and 786 have the same title. Is that a mistake? Jimmy C (talk) 01:07, 24 October 2012 (UTC)

- It may very well have been on xkcd itself; there was a bit of a snafu when Randall posted the image. That's part of the reason why we decided on number+name here, to ensure that that sort of naming collision couldn't be repeated. -- IronyChef (talk) 04:39, 24 October 2012 (UTC)

- It's also worth mentioning that 786 is both the number of the other strip, and the number of planets in this one. 93.144.215.90 22:38, 16 April 2013 (UTC)

The image isn't appearing for me. I think it's a problem with the thumbnail system. Bugefun (talk) 18:15, 27 December 2012 (UTC)

Same on ipad. DruidDriver (talk) 07:12, 17 January 2013 (UTC)

And on Firefox. --68.200.188.141 01:01, 27 January 2013 (UTC)

Not showing up in Chrome. Alpha (talk) 23:14, 2 February 2013 (UTC)

As a side note, the pace at which we're discovering exoplanets is accelerating. The first confirmed planet-sized mass outside our solar system was discovered in 1992, and it was ten years until we could celebrate the discovery of the 100th exoplanet. In the fifteen months since this comic was posted, another 156 exoplanets have been discovered (source: Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia, which lists 942 exoplanets as of 2 Sep 2013). Frijole (talk) 22:41, 10 September 2013 (UTC)

There are 786 exoplanets listed in the comic, And the previous comic about exoplanets is comic 786..... Coincidence? 108.162.222.44 08:58, 3 December 2013 (UTC)

- I think it's possible that he was waiting for the count to increase to that number to create some sort of meta-pun. With Randall, you never know, but the odds of that happening independently seems unfathomable to me. 108.162.238.117 16:12, 4 December 2013 (UTC)

- Additional comment: I believe the original filename for 768 was just "exoplanets.png" before being changed to "exoplanets_2010.png" when this comic was released. Any website that hotlinked the first comic would have their image replaced with the newest one. 108.162.238.117 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Does anybody else see this and think colorblindness test? 173.245.55.86 22:43, 23 January 2014 (UTC)

- Absolutely. Saw this from across the room (sometimes my machine takes a while to load) and thought it was a colourblindness statement rather than a planetary one. 162.158.6.128 20:41, 22 December 2020 (UTC)

- Three levels deep.. Remind anyone of Inception?A2658742 (talk) 08:36, 25 October 2014 (UTC)

This comic is referenced on exoplanet.eu, a professional site for exoplanet scientists, as the first link on a page titled "General professional Web sites relevant to extrasolar planets". The actual link goes to an interactive version of the page, but the link is at http://exoplanet.eu/sites/ labeled "Exoplanets: an interactive version of XKCD 1071". The actual interactive page is http://codementum.org/exoplanets/ . N. Kalanaga 13:58 (UTC-4) 10 April 2016

Was it actually 786 exoplanets known back then, or 786 planets including both the exoplanets and our own solar system? I would read the caption the latter way. This would make the number of exoplanets 778, like they also count it here and here, while this explanation here mentions 786 exoplanets several times. --YMS (talk) 09:25, 9 December 2017 (UTC)

- I could count them, but... I don't really feel like spending ~4 minutes straight on counting dots. 172.69.54.123 10:26, 29 March 2018 (UTC)

Add comment

Add comment