1381: Margin

| Margin |

Title text: PROTIP: You can get around the Shannon-Hartley limit by setting your font size to 0. |

Explanation

This is a reference to Fermat's Last Theorem, of which Pierre de Fermat claimed he had a proof that was too large to fit in the margin of a copy of Arithmetica. Despite its simple formulation, the problem remained unsolved for three centuries; it was cracked only with advanced techniques developed in the 20th century, leading many to believe that Fermat didn't actually possess a (correct) proof (see trivia).

In the comic, the person writing in the margin attempts to pull a similar trick, without actually having any proof, by claiming that they have found a proof that information is infinitely compressible, but pretending not to be able to show it due to lack of space in the margin. In this particular case, however, this approach backfires, precisely because if information was actually infinitely compressible, the writer would be able to fit the proof in the margin (due to his own proof). The writer realizes that if they had a proof, they should be able to fit it into the margin, and thus they realize that they cannot pull this trick. Or perhaps the writer really thought they had a proof, but then realized that their statement was a counterexample, and was disappointed that their idea for a proof was wrong.

What it seems they did not realize, is that it would be impossible to read the proof if the writer actually was able to compress their proof to fit in the margin. This is because you would need to know the algorithm described in the proof before you could decompress the proof text so you can read it. So they could actually have used this trick instead, writing that they had compressed it into - say a dot "." - and then people would have to find his proof to read it. And since they cannot find such a proof - they could not check their dot. Unfortunately this would also have backfired - because there is already a proof that this is not possible!

Another thing that they probably didn't realize, is that finding a proof for something being possible does not necessarily mean inventing an actual algorithm to do that particular thing. If the person claimed having found a non-constructive proof for such an algorithm, their statement at least wouldn't contradict itself.

The title text, yet another protip, makes a reference to the Shannon–Hartley theorem, which limits the maximum rate at which information can be transmitted. Setting the font size of text only changes its representation on the screen, and not the actual characters themselves. Trying to decrease the amount of space needed to store or transmit it like advised would be nonsensical. Another possible interpretation is that if you set the font size to 0, the text cannot be seen, and therefore, nothing is being transmitted period.

In the case of actual printed paper, decreasing the font size is valid technique for information compression (more information on the same page), as used in ie. microform. However, this comes at the cost of an increased spatial bandwidth (number of black/white transitions per distance). In the end, the resolution of the printer/paper/microscope chain limits the minimal font size that remains useable (above the Nyquist rate).

Transcript

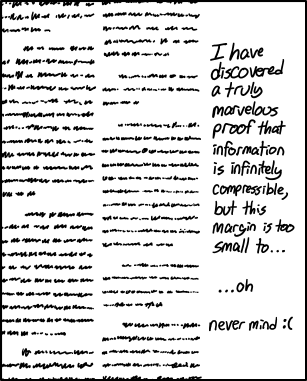

- [Written on the right margin of a page:]

- I have

- discovered

- a truly

- marvelous

- proof that

- information

- is infinitely

- compressible,

- but this

- margin is too

- small to...

- ...oh

- never mind :(

Background to Fermat's Last Theorem

- Fermat's Last Theorem states that no three positive integers a, b, and c can satisfy the equation an + bn = cn for any integer value of n greater than two.

- In the case with n=2, a b and c are the sides of a right triangle. There are an infinite number of integer solutions for a, b and c, such as 32 + 42 = 52. This was known to Euclid, but was used by land surveyors in Egypt and Mesopotamia over 1000 years before Euclid's time.

- Fermat's Last Theorem was solved in 1995 by Andrew Wiles with some assistance by Richard Taylor who helped him close a gap in his original proof from 1993.

- The proof involved some of the most complicated mathematics used today, and it has been speculated that only a handful of people in the world would be able to understand it.

- For people interested in the subject, Simon Singh has written a popular science book about it, called Fermat's Last Theorem.

- There are US Patents in this very area, analyzed by Jean-loup Gailly.

Discussion

Isn't it possible that a mathematician knows about the existance or the proof of something, but doen't know how to technically do it? In this case, the margin remark would be accurate and not so funny. They have found a proof of existance for infinite information compression, but not yet discovered an actual method to do it. 141.101.104.56 05:32, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Yes, when there's no example, it's called a pure existence theorem. If you actually demonstrate an example, that is a constructive proof. Mattflaschen (talk) 05:38, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Actually the proof of the Shannon-Hartley theorem is non-constructive. It tells you the data rate of the best possible channel coding, but does not tell you how to achieve it! 108.162.215.47 07:58, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

Setting font-size to 0 would be the same as not printing any information at all, you'll still use the same number of bits and be able to send the text to other computers which can read the information. The Shannon-Hartley theorem is, as far as I can see from the wikipedia article, about analogue channels anyway. --Buggz (talk) 06:16, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- The Shannon-Hartley theorem is about sending digital data (over analogue channels but you cannot send them over anything else in real world anyway). Nevertheless, you are right that setting the font size won't change the number of bits needed to be sent (font size specifies the size of the representation, not the information itself) therefore it won't change the limit. STEN (talk) 22:12, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- If you consider the paper itself as an analogue channel, then setting the font size to 0 before printing on the paper will "compress" information of any length to a single white sheet of paper. Decompressing it is not that difficult, but the method is a bit too large to fit here.141.101.104.40 13:09, 24 June 2014 (UTC)

Isn't this also a reference to Jan Sloot's digital compression mechanism where a movie would fit into 8 kbyte? Kaa-ching (talk) 07:36, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

This was my first time editing Explain XKCD, but I fear I may have went too far in replacing the current explanation of the title-text with my own and removing the incomplete tag. Is it OK? YatharthROCK (talk) 08:10, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- I think you title text explain seems fine (I have not checked on the Shannon theorem.) But I think it is too soon to make this explain marked as complete. So I have undone that. Great to have one more to edit the explain so keep up the good work. Kynde (talk) 10:46, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

Is the problem behind Fermat's Last Theorem "deceptively simple" or "deceptively difficult"? I've never quite worked out which way it should be. Unlike "cheap at half the price" which really should be "cheap at twice the price" and the effect of putting in the word "only" into "glass ... half full/empty". But I bet you all could care less (or, more accurately, "couldn't care less", because you already do not care at all), right? ;) 141.101.98.232 11:44, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- I believe the correct wording would be "deceptively difficult". Deceptively simple would imply that the problem looked quite difficult on the surface, but once work had begun it was found to be quite simple. Fermat's last theorem goes the other way. It is simply stated with very few elements, so it would seem the proof should be easily constructed, but is actually quite difficult. 173.245.50.72 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Unfortunately "deceptively easy" could also mean the opposite: it's easy, but only as a deception, so it's actually difficult. As of now, not even linguists have settled the question. It is just better to avoid the word unless the context can disambiguate the meaning. 141.101.99.32 05:14, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

Is it at all possible that the exclamation: "oh," represents the discovery of an earlier proof (perhaps even better than the one purported) all ready in the margin? That would explain the next exclamation: "never mind." This is a comic after all. And what's with the unreadable Lorem Ipsum text (perhaps a proof in itself)? Of course, the unhappy face (after "never mind") is a visual image compression mechanism that may deserve comment as well. Run, you clever boy (talk) 14:36, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Why bury descriptions of the beautiful inspiration behind these great comics in an afterthought "trivia" section?

I think explanations of the beautiful inspirations for these comics (like Fermat's last theorem, here) should be highlighted in the main part of the article, not buried below the transcript and demeaned with the label "trivia". Nealmcb (talk) 12:46, 13 June 2014 (UTC)

- Well there is a link from the relevant part. The inspiration of this comic is that someone wrote a statement in a margin and did not have space for the proof. It is not the theorem in it self that is the inspiration. Writing about Phytagoras and formulas in the explain is maybe a little too much. I think it belongs well in the trivia section and it is not buried - with this short transcript you can easily see there is more to the explai. Kynde (talk) 05:49, 14 June 2014 (UTC)

"" leading many to believe that he didn't actually possess a (correct) proof"" Of course Fermat did not have a proof. Was that margin the only free piece of paper in France then? For that reason in German one does not speak of Fermats "theorems", but the names used are Fermat's little or resp. big problem. If some nobody had written that margin, of course that would have been named a conjecture at best. Because Fermat was a real "big shot", a medium expression is used: "problem". But never theorem, because a theorem without proof isn't a theorem. 17:18, 14 June 2014 (UTC)108.162.254.138

- Who says he did not write his proof somewhere else, on a paper that was lost. It is only because the book was easily sored that we have all of Fermat's theorems. There were many in his book, and all of them - including the last - turned out to be true theorems. I do not believe he had the proof - but that is beside the point. If it had been a nobodu, then the book would never have been investigated... Anyway this has of course nothing to do with this explanation - but an interesting observation here in the talk page ;-) Kynde (talk) 07:11, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

What if the margin text is the compiled form of the proof? 141.101.105.187 04:46, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- Then he would not have written the oh... :( never mind Kynde (talk) 07:11, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- Maybe the "oh... nevermind" is part of the proof... --108.162.254.185 10:31, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- And maybe you had a point, but I'm afraid neither seems very likely ;-) Davii 141.101.99.189 23:49, 15 June 2014 (UTC)

- The "oh... :( nevermind" is simply the key required to decrypt the proof. 103.22.201.239 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- You are right, I just decoded it using that key! I'm afraid the full text of the proof is quite large and can't fit here.108.162.218.71 12:58, 24 June 2014 (UTC)

- Maybe the "oh... nevermind" is part of the proof... --108.162.254.185 10:31, 15 June 2014 (UTC)