681: Gravity Wells

| Gravity Wells |

Title text: This doesn't take into account the energy imparted by orbital motion (or gravity assists or the Oberth effect), all of which can make it easier to reach outer planets. |

Explanation[edit]

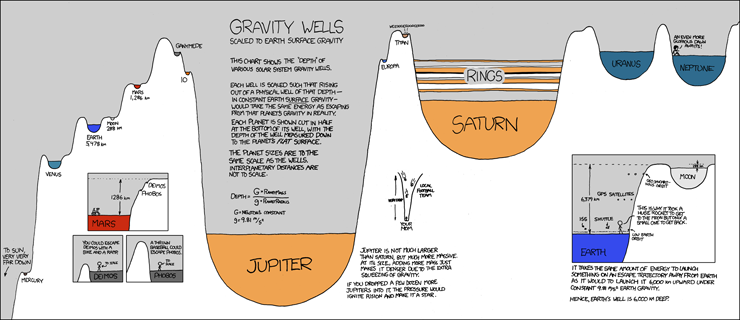

The comic shows the gravitational potential (energy transferred per unit mass due to gravity) for the positions of each planet in the solar system — including some moons and Saturn's rings. An object traveling along an upward slope loses energy, while an object traveling along a downward slope gains energy. Escaping a planet or moon's orbit requires enough energy (e.g. by walking, jumping, or rocket) to reach the top of either peak that defines the edge of the well. The peak to the left indicates the minimum energy required to exit orbit. The peak to the right indicates the maximum energy required to exit orbit. In order to exit orbit with the minimum amount of energy, you would have to travel towards the center of the solar system; to exit orbit with the maximum amount of energy, you would have to travel away from the center of the solar system (the Sun). In reality, the strength of gravity decreases with distance from the planet. However, a comparison of energy expended to escape the gravitational pull allows for a simpler comparison between the objects.

The height of the graph is scaled to kilometers via the gravitational potential an object has at the given height assuming at a constant acceleration due to Earth's surface gravity. The Sun's gravity well is not shown in its entirety, but is just indicated on the far left as "Very very far down". Had it been shown in its full extent it would have made the rest of the drawing so small in comparison that it would have been unreadable. As the gravitational potential increases with distance from the sun, the graph has a general upward slope. To rise out of each well on the diagram, and therefore escape the planet's gravity, it would require the same energy required to rise out of a physical well of that depth at Earth's surface gravity.

The length of each gravity well is scaled to the diameter of the planet and the spacing between the planets is not to scale with distance from the sun. This is necessary to make the graph readable. Because the distances between the planets are condensed, the gravitational potential - from the gravity pulling toward the sun - accumulates quicker. This is the reason for the large peaks between the planets. The moons shown in the chart are at the appropriate distance from their respective planets' gravity wells for their orbits. Each planet is shown cut in half at the bottom of its well, with the depth of the well measured down to the planet's flat surface.

Inner Planets[edit]

- Mercury — no facts listed

- Venus — no facts listed

- Earth and Moon: The listed depth of the gravity well at Earth was originally listed at 5478 km rather than the correct value of 6379 km seen in the cutout. Randall has since corrected it. The Moon's is 288 km.

- Mars: The listed depth of the gravity well of Mars is 1286 km.

Outer Planets[edit]

- Jupiter: Jupiter is so massive and dense that it is one thirteenth the mass of a small Brown dwarf which is the smallest kind of star. Saturn, while similar in size, is composed of much lighter gas material. Hence Saturn's mass and therefore its gravitational pull are much smaller. If a few dozen times the mass of gasses contained in Jupiter had condensed in that location, the gravitational pull would cause the pressure and temperature to increase to a level that is sufficient to ignite nuclear fusion. Had that happened during the creation of our solar system, we would have two Suns and our solar system would be a Binary system. Jupiter has 67 moons of which 3 are shown;

- Saturn: The diagram shows the position of the rings of Saturn in Saturn's gravity well. Saturn's rings start fairly near the planet and extend out quite far, therefore multiple stripes are shown in the figure. The rings are also shown in multiple colors and roughly match the observed colors from photos take by the Cassini spacecraft expedition as it passed Saturn. All of the colors of the planets and moons represent the predominant color of that object as observed from earth. Saturn has 62 moons of which one is shown;

- Titan, a moon of Saturn. The figures on Titan are sirens, a reference to Kurt Vonnegut's The Sirens of Titan.

- Uranus: Notably absent is any "your-anus" jokes.

- Neptune: Megan's quote is a paraphrase of Carl Sagan's quote, "...but from a planet orbiting a star in a distant globular cluster, a still more glorious dawn awaits, not a sun-rise, but a galaxy rise." Video here

Cut outs and sketches[edit]

The following items are listed from top to bottom and left to right.

- Mars moons: The Mars cutout shows the Mars moon system, including the moons Deimos and Phobos. The depth of the Mars gravity well is listed at 1286 km.

- Your mom and a local football team: The sketch next to Jupiter is playing on the classic "Yo Mama" joke. It combines "Yo Mama is so fat" and "Yo Mama is so horny". The sketch implies that she has a huge gravitational pull because she is very fat, and has sex with an entire football team by demonstrating a football team falling into her very deep gravity well. A "Yo Mama" joke also appears in comic 89: Gravitational Mass.

- Earth's Moon: The cut out shows the significant difference in strength between the gravity well of the Earth and the Moon. Cueball comments that the Apollo Lunar Module was very small and the Saturn V rocket was very large because escaping the Earth's gravity well takes much more energy than escaping the Moon's. The cut out also shows objects like the International Space Station, the space shuttle, GPS satellites and geo-stationary satellites at their respective positions within Earth's gravity well. The depth of Earth's gravity well is listed correctly at 6 379 km (note the difference from the non-cutout number). The depth of the Moon's gravity well is listed at 288 km.

How to calculate gravity wells[edit]

The text near the bottom of Jupiter's gravity well explains that the depth of the well is mass-of-planet over radius-of-planet with Newton's constant and 9.81 m/s² as constants, where 9.81 m/s² is the acceleration of a free falling body at Earth's gravity.

The calculation for a gravity well is:

- depth = (G * Planet-mass ) / (9.81 m/s2 * Planet-radius)

- where G is Newton's gravitational constant, and

- 9.81 m/s2 is the acceleration rate of a free falling body on earth at sea level (g).

Title text[edit]

The title text indicates that the planets motion can affect the amount of energy for escape velocity. It is possible to change speed by using the planets orbital speed and gravity. This is known as a performing a slingshot or a gravity assist, and is done to gain speed or to brake when needed. The use of rocket engines are more effective when used at a high speed slingshot maneuver, which is known as the Oberth effect, where most energy is going into moving the rocket as opposed to moving the exhaust — conserving the maximum useful energy. On earth the same principle is used when launching rockets. Rockets are always launched in an eastward direction to make maximum use of the rotational energy of the earth. Launching rockets in a westward direction would require significant additional energy. Because of this most artificial satellites are flying east around the globe.

The size of the gravity-well as described in this comic is not accounting for these factors. Therefore, leaving the solar system (or any of the gravity wells of the planets) could require less energy than described by the graph, assuming that the launch and slingshots are properly designed and executed.

Escape Velocities[edit]

The following table was adapted from the table in Escape velocity, using h = V_e^2 / 2g:

| Location | with respect to | Ve (km/s) | Well depth (km) | Location | with respect to | Ve (km/s) | Solar well (Mm) | Total depth (Mm) | |

| on the Sun, | the Sun's gravity: | 617.5 | 19,435,000 | 19,435 | |||||

| on Mercury, | Mercury's gravity: | 4.3 | 942 | at Mercury, | the Sun's gravity: | 67.7 | 233.6 | 235 | |

| on Venus, | Venus' gravity: | 10.3 | 5,407 | at Venus, | the Sun's gravity: | 49.5 | 124.9 | 130 | |

| on Earth, | the Earth's gravity: | 11.2 | 6,393 | at the Earth/Moon, | the Sun's gravity: | 42.1 | 90.3 | 97 | |

| on the Moon, | the Moon's gravity: | 2.4 | 294 | at the Moon, | the Earth's gravity: | 1.4 | 91 | ||

| on Mars, | Mars' gravity: | 5 | 1,274 | at Mars, | the Sun's gravity: | 34.1 | 59.3 | 61 | |

| on Jupiter, | Jupiter's gravity: | 59.5 | 180,400 | at Jupiter, | the Sun's gravity: | 18.5 | 17.4 | 198 | |

| on Ganymede, | Ganymede's gravity: | 2.7 | 372 | ||||||

| on Saturn, | Saturn's gravity: | 35.6 | 64,600 | at Saturn, | the Sun's gravity: | 13.6 | 9.43 | 74 | |

| on Uranus, | Uranus' gravity: | 21.2 | 22,907 | at Uranus, | the Sun's gravity: | 9.6 | 4.7 | 28 | |

| on Neptune, | Neptune's gravity: | 23.6 | 28,400 | at Neptune, | the Sun's gravity: | 7.7 | 3.02 | 31 | |

| on Pluto, | Pluto's gravity: | 1.2 | 73 | ||||||

| at Solar System galactic radius, |

the Milky Way's gravity: | 525 | 14,000 |

Transcript[edit]

- Main Text

- Gravity Wells scaled to Earth surface gravity

- This chart shows the "depth" of various solar system gravity wells.

- Each well is scaled such that rising out of a physical well of that depth — in constant Earth surface gravity — would take the same energy as escaping from that planet's gravity in reality.

- Each planet is shown cut in half at the bottom of its well, with the depth of the well measured down to the planet's flat surface.

- The planet sizes are to the same scale as the wells. Interplanetary distances are not to scale.

- Depth = (G × PlanetMass) / (g × PlanetRadius)

- G = Newton's constant

- g = 9.81 m/s2

- Planetary Descriptions

- To Sun, very very far down

- Mercury

- Venus

- Earth - 6379 km [originally 5,478 km]

- Moon - 288 km

- Mars - 1,286 km

- Ganymede

- Io

- Jupiter

- [A drawing of a "very deep" gravity well, "Your mom" at the bottom, several member of "local football team" falling down towards her.]

- Jupiter is not much larger than Saturn, but much more massive. At its size, adding more mass just makes it denser due to the extra squeezing of gravity.

- If you dropped a few dozen more Jupiters into it, the pressure would ignite fusion and make it a star.

- Europa

- Titan

- Two alarms: Weeoooeeoooeeooo

- Saturn

- Rings

- Uranus

- Neptune

- Megan: An even more glorious dawn awaits!

- Mars Inset

- [Mars gravity well, with one of the Mars rovers on its surface, with its moons Deimos and Phobos as smaller gravity wells.]

- [Figure of a man (to scale) in Deimos's gravity well.]

- You could escape Deimos with a bike and a ramp.

- [Figure of a man (to scale) in Phobos's gravity well.]

- A thrown baseball could escape Phobos.

- Earth Inset

- [Zoomed-in view of Earth/moon gravity well, featuring the relative locations of the atmosphere, Low Earth Orbit, the International Space Station, the Space Shuttle, GPS satellites, and satellites in geosynchronous orbit.]

- Cueball: This is why it took a huge rocket to get to the moon but only a small one to get back.

- It takes the same amount of energy to launch something on an escape trajectory away from Earth as it would to launch it 6,000 km upward under constant 9.81 m/s2 Earth gravity.

- Hence, Earth's well is 6,000 km deep.

Trivia[edit]

This comic used to be available as a poster in the xkcd store before it was shut down.

Discussion

Why is Earth's well's depth listed as 5478km but as 6379km in the inset? Compare with Mars which has 1286 in both places. 87.174.225.131 07:21, 12 April 2013 (UTC)

- Best guess is either a goof, or that the lower number is just for Earth itself, while the greater number is for the Earth/Moon system as a whole. Proportionally speaking, we have the largest moon in the solar system, so maybe it wouldn't nicely fit in the Earth well as easily as Mars's and Jupiter's moons do.--Druid816 (talk) 08:28, 12 April 2013 (UTC)

- It may be the height needed to go from one gravity well to another. You don't have to get all the way up to escape speed for that.

- Randall wasn't kidding about the Sun being "very very far down"; its well is 100 times deeper than Jupiter's!

- Wwoods (talk) 19:47, 12 April 2013 (UTC)

- OTOH, from the table above i'm thinking that the 5.4 might be the Venus figure, and it was wrongly placed besides Earth...

- Secondly, what i found interesting was that the Earth's 6.4 looks so much like its radius! I wonder if it's merely a coincidence, or there's a connection between the two... -- 141.101.99.233 21:25, 30 October 2013 (UTC)

- The fact that the density of the Earth is 5478 kilograms per cubic kilometer makes me pretty sure it is a typo. Fewmet (talk) 03:04, 4 July 2014 (UTC)

- Hehe, you might be right. That's the best explanation. It would be a strange coincidence otherwise. But your units are wrong: a cubic kilometer of water, ice-cream or Natalie Portmans would be already something like a billion kilograms. Or a trillion, if you are American. Oh, you might be American. In this case: happy 4th of July! -188.114.102.35 12:39, 4 July 2014 (UTC)

- Thanks for catching that (and for the July 4 wishes). It should be kilograms per cubic meter. Looking into that, though, leaves me less sure that is the origin of the problem. I thought I had multiple sources for Earth having a density of 5478 kg/m3, but can find only one (and not a very compelling one at that). I have sounder sources for 5513 kg/m3. 5514 kg/m3, 5515 kg/m3, 5520 kg/m3 and 5540 kg/m3. It may be trivial in that all round to 5500 kg/m3.

- It was corrected on the poster version. Earth's well in the main graphic is marked as 6379km, just like the inset.108.162.216.86 00:19, 21 August 2014 (UTC)

- Hehe, you might be right. That's the best explanation. It would be a strange coincidence otherwise. But your units are wrong: a cubic kilometer of water, ice-cream or Natalie Portmans would be already something like a billion kilograms. Or a trillion, if you are American. Oh, you might be American. In this case: happy 4th of July! -188.114.102.35 12:39, 4 July 2014 (UTC)

The Oberth Effect mentioned in the title text is well-explained here (assuming you are not intimidated by the algebra in squaring a binomial). The gist of it is that using a bit of fuel in a rocket thrust will increase the rocket’s kinetic energy . The higher the kinetic energy at the time of the thrust, the greater the increase in kinetic energy. It works because the energy of the fuel goes into increasing the kinetic energy of the ship and the kinetic energy of the spent fuel. The faster you go, the greater the portion of the energy the ship gets.

- The image at the top is out of date and should be fixed as well as the earth's comment about how it's different--172.70.178.107 10:52, 7 September 2022 (UTC)

- I, for one, don t understand at all what you think is out-of-date/different. There's a new planet, or some rescaling of gravity? If serious, do elaborate. (If not serious, elaborate to add to the humour.) 141.101.99.154 12:27, 7 September 2022 (UTC)

The “gravity assist” is also known as the slingshot effect. The Wikipedia explanation is good, especially with its diagram. In it a spaceship (or other body) accelerates toward a planet (or moon, star, etc.) in the same direction that body was going. The ship picks up a little of the body’s momentum and so goes faster, although only according to an external reference frame. An observer at rest with respect to that other body would actually see the ship approach and depart with the same speed.

The title text reference to orbital speed is unclear to me. I suppose it just means that the given gravity wells assume you are at rest on the surface of the planet. Then being in orbit (and necessarily having an orbital speed) would mean you are part way out of the well already. Fewmet (talk) 02:57, 4 July 2014 (UTC)

If the first stage of a rocket is still supplying lift for a while after its fuel is used up and the stage is cut adrift, would there be any saving in waiting for the next phase to cut in when forward motion is almost ended rather than continuing the burn immediately from the second stage?

The higher the vehicle gets the more productive the fuel becomes.Or is it preferable to continue the journey as fast as possible? -- Weatherlawyer (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

My first instinct would be to say burn as continuously as possible. If you wait until your speed is almost zero, you have to use a whole load of energy (fuel) to get back to the speed you were going in the first place. --Pudder (talk) 17:12, 27 January 2015 (UTC)

- Hence the need to use ultra light containers in the first stage? -- Weatherlawyer (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Maybe the typo is based on Randall's days at NASA? It might already incorporate gravity assists and the Oberth effect. That number might even be what NASA was using as the minimum potential with known cost-effective techniques. flewk (talk) 21:22, 8 January 2016 (UTC)

Earth's Geosynchronous Orbital Altitude[edit]

In the XKCD strip, the artist states above Earth in the lower right popout that the geosynchronous altitude is well below top of Earth's gravity well. While the rest of his strip is a wonderful representation of the science behind gravity wells, this one bit is not accurate. A geosynchronous altitude for Earth is nearly 36,000 km, not under 6000 km. Kudos for the rest of the strip, though.

- The strip scales the heights of the corresponding wells based on the assumption of constant Earth surface gravity; in other words, it takes the same amount of energy to climb such a well as it does to escape the real gravity well. By contrast, as one ascends from the Earth's surface, gravity decreases, so it requires less energy to climb to an orbital altitude than it does to reach the same height in the hypothetical well. The amount of energy required to put a geostationary satellite in orbit, for example, is equivalent to that used in raising it 5413 km in Earth surface gravity, and thus it is located 5413 km from the bottom of the well. Arcorann (talk) 03:42, 8 February 2019 (UTC)

I have a question relating to this topic. I've learnt how to calculate well depth, but how did Randall Munroe calculate the position of things inside the gravity well (moons of planets, for example, or Saturn's rings)?

- I'm also confused by this. Anyone have the answer? 162.158.78.78 17:50, 5 May 2020 (UTC)

- You can use the same formula as in the explanation: D = GM/(gd), where D is the depth in the gravity well, G is the gravitational constant, M is the mass of the planet, g is acceleration due to gravity on Earth's surface (9.81 m/s²) and d is the distance from the center of mass of the planet. Note that D is the depth in the well, while d is the distance from the center of mass, so they are reversed (one counts "from the top", the other "from the bottom"). In the explanation, d is substituted for the radius of the planet (i.e. the distance from the center of the planet to its surface), which is useful because that's where you would consider yourself "on the planet", and also where you would launch your rockets (or baseballs) from. That said, you can also use other values. E.g. for Saturn's rings: Saturn has a gravity well depth of ~66000 km at its surface; rings are 7000 to 80000 km above its equator, or 67000 - 140000 km from its center of mass; that gives them the depths in the gravity well of ~57000 to ~28000 km, or 90% to 40% (once again, counting from the top). This about lines up with the comic. (also note how things at the very top of the gravity well are infinitely far away from the actual planet). 185.70.55.130 15:40, 8 August 2025 (UTC)

- By a subtly different measure, I imagine the relationships between base-of-well and lip-of-well (positions where you're on the edge of either a sall near body or a larger more distnt one) are summed and combined in a similar way to this kind of delta-V map gives you certain place-to-place relationships (required transition gains and losses). 92.23.2.228 20:33, 8 August 2025 (UTC)

How much gravity can be overcome?[edit]

How much of the gravity well can be overcome by launching from a high mountain?

If we constructed a spaceport on a mountaintop that was, say, 14,505 ft (Mt. Whitney, CA), or even 20,310 ft (Denali, Alaska), or slightly less after clearing a flat surface, would it significantly reduce the amount of the gravity well a rocket had to climb, and hence the amount of fuel needed to reach LEO? Would thinner air reduce drag and increase efficiency significantly as well? This would be tough to build and maintain, but would it be worth delivering spaceships to mountaintops by truck to reduce the need for fuel to escape Earth's Gravity well?

- I am not an expert, but to my knowledge, the effect of latitude on gravity is much stronger than those of a mountain. Especially one as far north as Denali. That is why Nasa uses Florida and Texas, Russia uses Baikonur_Cosmodrome in Southern Kazakhstan , Europe uses Guiana_Space_Centre in south america (French Guiana, so technically Europe...). --Lupo (talk) 08:52, 29 May 2019 (UTC)

- The reason we build spaceports closer to the equator is not any effect on gravity, but rather the fact that Earth "moves" (in a linear sense) faster at the equator, therefore you don't need to spend as much fuel to accelerate to orbital velocity, assuming you are going eastwards. For polar orbits (where you go around the earth north-to-south or vice versa), you can launch from anywhere you like (hence Plesetsk, Kodiak, Vandenburg, etc). For (rare) westward launches, you want to be as far away from the equator as possible. 185.115.7.100 11:29, 8 August 2025 (UTC)

- FWIW in the early stages of planning the Space Shuttle, the Air Force was looking at launching from the top of the Rockies, maybe in Colorado or such. The reason being exactly the savings in propellant and consequent gain in payload. I was made to believe the savings was quite significant.

- What killed it was the issue of what happens when one malfunctions or crashes on launch. You've got Space Shuttle & parts raining down on the Denver metro area; not good.

- Source: My dad worked on the project for the Air Force back in the 70s or thereabouts. Flug (talk) 21:52, 22 September 2019 (UTC)

I think the sentence "This is why it took a huge rocket to get to the moon but only a small one to get back" is wrong (or at least very misleading). The main reason for this is that the "huge" rocket has to carry the "small" rocket all the way to the moon, while the "small" rocket only has to carry back its useful payload, so of course the "huge" rocket will have to be much bigger as per the rocket equation. The secondary (and more interesting) reason is that the "big" rocket has to (1) ascend through the Earth's atmosphere (which takes a lot of energy due to drag), (2) escape most of the Earth's gravity well, (3) slow down enough to land at the Moon; while the "small" rocket doesn't have to deal with an atmosphere on its way up, and doesn't need to slow down at Earth using its own engines because it can aerobrake (use the drag of the atmosphere to slow down). If neither Earth nor Moon had an atmosphere, and your rockets only had to go one way (i.e. didn't have to carry a return vehicle on them), then the rockets would be roughly the same size.

If noone minds within a couple days, I will note this in the explanation. 185.115.7.100 11:22, 8 August 2025 (UTC)