230: Hamiltonian

| Hamiltonian |

Title text: The problem with perspective is that it's bidirectional. |

Explanation[edit]

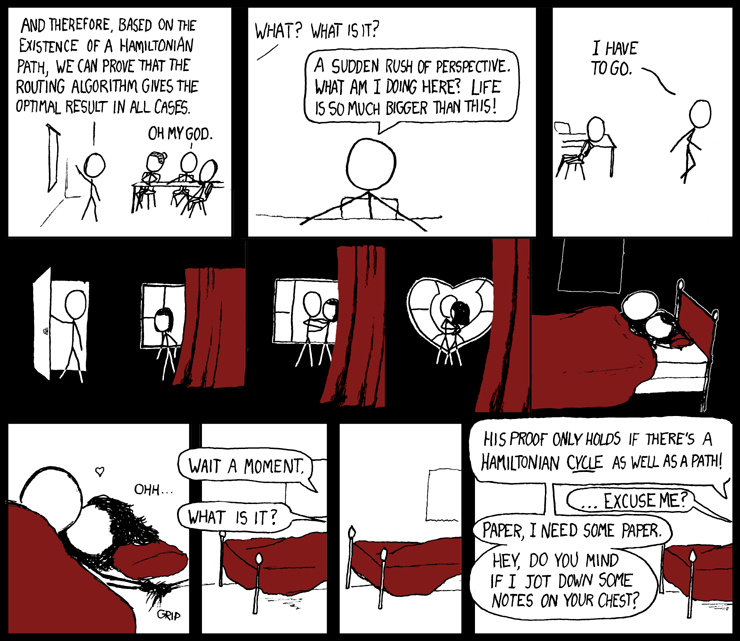

Cueball, presumably in class, decides that the subject of optimizing routing algorithms is not important in the larger context of life and love. However, he later realizes while in bed with Megan that there is a flaw in the proof presented, and suddenly wants to focus on the mathematics again, in a humorous reversal of his position about what is meaningful.

In graph theory, a Hamiltonian path is a path that connects all the vertices (nodes) and passes through each one exactly once. (Think connect the dots with rules!) A Hamiltonian cycle is a Hamiltonian path such that the final vertex is adjacent to the initial one (intuitively, it "begins and ends with the same vertex," but recall that paths are required to only pass through each vertex once). The presenter is using graph theory to optimize a routing algorithm by solving a Hamiltonian path problem. Cueball's realization is that the proof he had followed in part actually requires a Hamiltonian cycle, not just a path, so the presenter's proof of the existence of a Hamiltonian path is insufficient to solve the problem.

The title text plays on a dual interpretation of bidirectional: just as any graph cycle can be traversed in two directions, a change in perspective can be traversed in two directions (from mathematics to love, and then from love to mathematics).

Transcript[edit]

- Lecturer: And therefore, based on the existence of a Hamiltonian path, we can prove that the routing algorithm gives the optimal result in all cases.

- Cueball: Oh my God.

- [Close-up of Cueball.]

- Offscreen: What? What is it?

- Cueball: A sudden rush of perspective. What am I doing here? Life is so much bigger than this!

- [Cueball running out of room.]

- Cueball: I have to go.

- [Cueball enters darkened room, where Megan waits by window.]

- [Cueball and Megan embrace...]

- [...and get into bed.]

- [A heart appears over the supine bodies.]

- Megan: Ohh...

- grip

- Cueball (out of frame): Wait a moment.

- Megan (out of frame): What is it?

- [Silence.]

- Cueball (out of frame): His proof only holds if there's a Hamiltonian cycle as well as a path!

- Megan (out of frame): ...excuse me?

- Cueball (out of frame): Paper, I need some paper. Hey, do you mind if I jot down some notes on your chest?

Discussion

I don't agree with the title's explanation. IMO the title refers to the fact the "sudden rush of perspective" happens to Cueball also when he is making love, but starts to think about the algorithms. 37.128.6.132 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

Fixed. Tenrek (talk) 08:56, 1 January 2014 (UTC)

When in math class, he walks out, likely offending his peers, because his mind is occupied with thoughts of love. When making love, he offends his partner because his mind is occupied with math. Some perspective! Mountain Hikes (talk) 01:28, 25 September 2015 (UTC)

- "... offending his peers"? This comic appears to happen in an academic environment (judging by the topics involved). Maybe the teacher would get offended (it depends on person) but not his classmates. They would probably be somewhat between confused and laughing (the situation has a great inside meme potential...), maybe also concerned (especially if their teacher was known to be serious about such things), but surely (at least according to my college experience) not offended. Bebidek (talk) 02:17, 4 December 2024 (UTC)

I always thought that the talk about the algorithm providing an "optimal result in all cases" was the reason Cueball left - he decided to apply the algo to his life somehow in a way that he would always find a positive outcome, such as love. That also made the end panel funnier for me because as he found a flaw in the algorithm, he self-fulfilled it by interrupting his romance, thus ruining the "optimal path in all cases". Could be wrong here... 108.162.237.254 03:54, 2 April 2016 (UTC)

There's an anecdote about the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauß, who is said to have jumped out of the bed in the middle of his wedding night, to write down some proof he just found... 162.158.203.144 19:39, 29 April 2016 (UTC)