378: Real Programmers

| Real Programmers |

Title text: Real programmers set the universal constants at the start such that the universe evolves to contain the disk with the data they want. |

Explanation[edit]

This comic is a satire on the idea of a Real Programmer. To quote Wikipedia "...the computer folklore term Real Programmer has come to describe the archetypical 'hardcore' programmer who eschews the modern languages and tools of the day in favor of more direct and efficient solutions—closer to the hardware." The implication is that modern programmers are coddled by today's tools of the trade, which eschew detailed understanding for simple workflows.

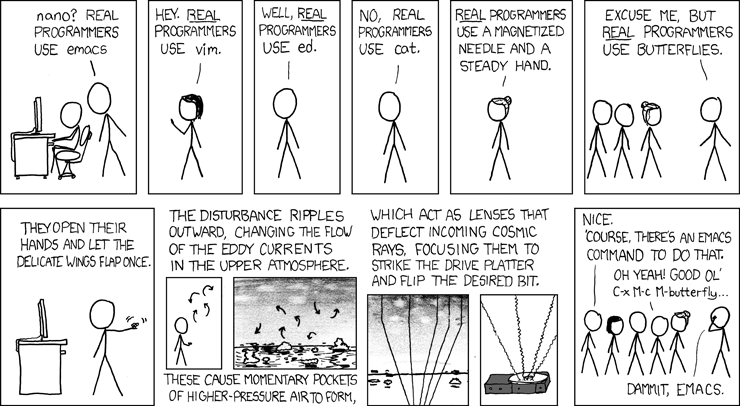

The first figure is writing a piece of code when another programmer ridicules him for using GNU nano. Nano is a text editor - a program often used to edit the source code of other programs. It is basic and relatively easy to use, even having instructions displayed prominently at the bottom of the screen. He goes on to say that "REAL" programmers use Emacs. GNU Emacs is a popular editor known for its vast profusion of features and extensions to perform all sorts of functions beyond simple text editing, and is widely regarded as one of the best examples of software that succeeds despite being fully overtaken by feature creep. The comic continues from here as a series of programmers state progressively more obscure or outdated methods, culminating in the final programmer who claims that "real" programmers use butterflies.

His description of his rather surreal programming method is ludicrously complicated and would require an absurd amount of knowledge and forethought to pull off, bordering on omniscience. In the final panel, the Emacs programmer claims that there's an Emacs code to do that.

The characters present progressively more "old school" solutions to the problem of editing code:

- Emacs and Vim are both text editors still in relatively wide use, with complex user interfaces and a range of features. While useful, neither is particularly easy to get started using. This high barrier to entry is what limits them to the so-called "real programmers".

- ed is a line editor. While relatively simple, it is extremely awkward to use since it was designed primarily for use on a teleprinter, not a computer screen at all. It does not even display the file the user is editing!

- cat is a Unix program that concatenates and outputs the contents of files; it's usually run from a Unix shell, which allows its output to be written or appended to a file. It isn't intended as an editor at all but is convenient to display files. Actually editing files with it would be even less convenient than ed.

- Using a magnetized needle to flip bits on a hard drive requires nanometric precision and intuitive mastery of binary code, but in the early days of programming, people did use needles sometimes to fix bugs on punched cards.

When the final character suggests the utterly surreal idea of using butterflies, he is referring to the Butterfly effect, a "phenomenon whereby a minor change in circumstances can cause a large change in outcome" as illustrated in the short story A Sound of Thunder. The joke at this point relies on stretching the connection between the ideas of "difficult-to-use" and "requires detailed understanding of underlying principles," to suggest that not only do Real Programmers know everything about how computers work, but they know how to manipulate the ambient physical environment in elaborate ways to cause computers to do what they want, akin to performing trick shots that accomplish feats of programming.

The fact that Emacs already has a command for this simply exacerbates the other programmers' frustration with modern coding tools. For reference, Emacs commands are usually referred to by the keyboard sequence required to activate them, such as "C-x M-c" (Control-x Meta-c (this would be typed by holding control and pressing x, releasing both, then holding alt and pressing c, then releasing both)), though this exact key sequence is a bit different from most Emacs commands. The butterfly programmer saying "Dammit, Emacs" plays on Emacs' notoriety for its kitchen sink design approach of including all of the features and options that anybody might ever conceivably want. For example, later versions of Emacs actually added a totally useless "M-x butterfly" command as an easter egg, in reference to this very comic.

The title text further suggests manipulating the universal constants in order to create a universe in which the required computer data will exist. Programming of this sort would require power and knowledge akin to the Abrahamic God.

According to the logic, the programmers shown may even represent the fulfillment of this master programmer's plan. The universe may have been designed in such a way that the programmer's ancestry would result in his parents, who would meet and have a child, who would learn to program and eventually find himself in a position where he undertakes the task of creating a program that fills the disk with the desired data. In tandem, of course, all of the people involved with creating and developing all the required hardware, software, raw materials, computer science, electricity, logic (etc., etc., etc.) would have to be part of the master plan. Put simply, it would probably be simpler just to use Emacs.

The use of a magnetized needle may also be a reference to the Apollo AGC guidance computer, whose instructions were physically written as patterns of wires looped around or through cylindrical magnets in order to record binary code.

This comic hints at the "editor wars," an ongoing debate of Vim and Emacs users over which of the two editors is better. The editor wars are mentioned again in 1823: Hottest Editors.

Transcript[edit]

- [A Cueball-like man sits at a computer, programming. Cueball stands behind him and looks over his shoulder.]

- Cueball:

nano? Real programmers useemacs.

- [Megan appears behind him.]

- Megan: Hey. Real programmers use

vim.

- [A second Cueball-like man appears behind her.]

- Ed Cueball: Well, real programmers use

ed.

- [A third Cueball-like man appears behind him.]

- Cat Cueball: No, real programmers use

cat.

- [Hairbun appears behind him.]

- Hairbun: Real programmers use a magnetized needle and a steady hand.

- [A fourth Cueball-like man enters, facing them all. We see him facing the last two Cueball-like men and Hairbun.]

- Butterfly Cueball: Excuse me, but real programmers use butterflies.

- [A Cueball-like programmer is standing much like Butterfly Cueball except for holding out a butterfly in front of his computer. The butterfly flaps its wings.]

- Butterfly Cueball (narration within the panel, not diegetic to the scene): They open their hands and let the delicate wings flap once.

- [The next two panels are smaller, and two sets of narrative text are written to span respectively above and below both panels. The first panel is the Cueball-like programmer with the butterfly and above him four curved arrows pointing up or down. The second panel shows the upper atmosphere, with large clouds far below and the earth even further down. Also here are shown seven of the same type of arrows.]

- Butterfly Cueball (narration above the panels): The disturbances ripple outward, changing the flow of the eddy currents in the upper atmosphere.

- Butterfly Cueball (narration below the panels): These cause momentary pockets of higher-pressure air to form,

- [The next two panels are also partial height, leaving room for narration spanning above both panels. The first panel shows the atmosphere, again with clouds, and four parallel lines coming from above, and then they begin to merge, getting quite close at the bottom of the panel. The second panel shows the four lines merging on a driver platter.]

- Butterfly Cueball (narration above the panels): Which act as lenses that deflect incoming cosmic rays, focusing them to strike the drive platter and flip the desired bit.

- [All the programmers who have commented so far stand in the order they have commented facing the last Cueball-like man, who slaps his forehead.]

- Cueball: Nice. 'Course, there's an emacs command to do that.

- Cat Cueball: Oh yeah! Good ol'

C-x M-c M-butterfly... - Butterfly Cueball: Dammit, Emacs.

Discussion

I was going to edit the above description, but it was taking too much time to edit it into a suitable format, so here's the long version.

In the beginning was UNIX. And it was good. And it was written by some very clever people.

One of the first very useful tools they wrote was ed, a "line-editor" (i.e. it works one line at a time). It uses some simple commands, and was created to work on very-old-school teletype machines, where you type a command, and ed types a response back.

It was a lovely bit of code. Using very little the way of resources, it allowed you to create a text document of any length, including source code in whatever language you wanted to program in.

Eventually, a more sophisticated version called ex (short for EXtended) was written by a clever man named Bill Joy. While it has some great improvements over ed, it was still a line-editor.

The trouble was, using a line-editor like ed or ex requires you to have a very good mental model of the document you are creating. Unfortunately, humans aren't very good at this, so they constantly need to refresh their mental model by printing out big chunks of the document (or program) they are working on. This took a LOT of paper using teletypes.

Eventually, teletypes were replaced with terminals. This saved a lot of paper. But the people who created the terminals began making them smarter than teletypes, so that magic character sequences could be used to move the cursor around, rather that simply going character-by-character across the line, then scrolling down to the next line, and so on. This opened up a whole new world.

The very clever Bill Joy took advantage of these magic character sequences to create his wonderful "full-screen" text editor vi. vi was the "VIsual mode" of ex. With vi, the user could see a screen-full of text at once. Entire forests were saved.

Emacs was developed at the same time as vi, using the same magic characters, and was also a full-screen text editor. I've never used it, so I can't speak to its merits, but there are many people who still find it more useful than any GUI they've tried.

On the one hand, vi and emacs are more sophisticated tools, and thus take longer to learn to use than ed. However, once you learn to use them, they make writing code EASIER, and they are therefore considered a less praise-worthy way of writing code by those concerned with defining what a "Real Programmer" is. (In other words, those programmers suffering from testosterone poisoning.)

Using cat to write a program looks like this: (Note that the $ is the prompt provided by the computer. The rest is typed by the user. And the ^D means the user held down the control key while typing the letter "d".)

$ cat | cc

The user types C code here, and ends with ^D. Assuming all goes well, the compiler silently finishes after creating the executable program a.out in the user's current working directory.

The reason this is considered a more praise-worthy way of coding is that, in those early days, doing this meant that your code was lost the instant you typed it. If you made a mistake, you would have to type the whole thing again. So doing this for code of any sophistication was considered an act of courage, confidence, and conviction. (I myself did it several times, for the fun of it, when no-one was watching, though never for a program that took more than about 30 lines of code. I was delighted that it worked all 3 times, but since I love to write re-usable code, this wasn't really something I wanted to keep doing.)

NOW PAY ATTENTION. VI IS NOT VIM! Vim was written in 1991, long after more sophisticated shells were created that made it possible to copy and paste text from one part of the screen to another. This ability greatly reduced the risks of using cat to pass your source code directly to the compiler, so it was no longer a praise-worthy stunt. Thus the line "Real programmers use vim" was NEVER considered true by any UNIX programmer.

Whether this was a mistake of the author, or the character (possibly Megan?) is unclear. It seems possible that it was a simple typo, but since I've never seen one in the strip before, I'm somewhat skeptical.

--MisterSpike (talk) 07:12, 17 June 2013 (UTC)

cat | ccdoesn't work on my system. Myccis simply a symlink togcc; what's yours? --Lucaswerkmeister (talk) 10:16, 7 August 2013 (UTC)

- One can also use

- $ cat | gcc -xc -

- The program will be an a.out file. 200.131.199.28 (talk) (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- These are officially worthy of a "useless use of cat award", and I hereby decree it so. RandalSchwartz (talk) 01:16, 9 January 2023 (UTC)

Some comments:

I would never claim to be an emacs expert, but I'm reasonably proficient in it. Command of the form M-x (whatever) are a way of calling commands (or, really, arbitrary functions in the emacs code) by name. SO 'M-x butterfly' means that there is a function named "butterfly" somewhere, but that it has not been assigned a keyboard shortcut (or it has, but you're calling it the long way).

Also, three are still advanced Linux programmers today who swear by vim or emacs being superior to IDEs. There are specific technical reasons for this: emacs is basically an IDE construction kit that's incredibly easy to extend and customize, and is more customizable than pretty much any other program in the history of software with the exception of a Smalltalk installation. And vim has highly evolved commands to give experts a superhuman typing and editing speed when coding.

So when someone claims that "real programmers use vim," they are claiming that RIGHT NOW, vim is the best possible editor for developers of sufficient competence. There's a community of very smart people that basically thinks this.

Tess (talk) 04:19, 15 December 2013 (UTC)

What is "Meta"? As in "M-butterfly"?108.162.219.180 23:20, 27 April 2015 (UTC) When I read this, I started up emacs and tried this... until I realized that there was no butterfly key... --108.162.215.58 00:51, 13 May 2015 (UTC)

- I own a Keyboardio Model 01 which includes a butterfly key, among other unique keys. I currently have mine mapped to "Mouse middle click" for use in Linux, due to a disagreeable mouse I haven't had time to take apart and clean. 172.70.114.136 00:22, 30 November 2023 (UTC)

"Meta" is binded to "Alt" in modern keyboard. "Meta" is referring to the "Meta" key in early LISP keyboard. --173.245.62.93 18:58, 19 May 2015 (UTC)

I assume this cartoon was inspired by an earlier User Friendly cartoon, in which Miranda ends an editor one upsmanship discussion by saying: "Well, I edited the inodes by hand. with magnets." See also this classic Dilbert cartoon. Espertus (talk) 21:56, 13 August 2015 (UTC)

Real programmers don't use any negative calls to sqrt(), of course. --199.27.128.114 22:07, 7 September 2015 (UTC)

August 1984 "Real programmers use cat as their editor." http://web.cecs.pdx.edu/~kirkenda/joy84.html --141.101.104.180 00:21, 18 October 2015 (UTC)

Could the title text be a reference to the novel "Heechee Rendezvous" by Frederik Pohl, in which an alien species causes the universe to start to contract, in order to provoke a new Big Bang which would lead to "improved" natural constants? --162.158.114.220 09:37, 2 December 2015 (UTC)

The title text is more likely a reference to the end of the book "In the Beginning Was the Command line", where programming / simulation develops to creating worlds on a single command line, specifying natural constants (in all their precision). Hrabbey (talk) 13:23, 30 March 2018 (UTC)

There has been a community portal discussion of what to call Cueball and what to do in case with more than one Cueball. I have added this comic to the Category:Multiple Cueballs. In this comic it cannot be said clearly that any of the four/five (if the guy with the butterfly in hand is not the same as the one speaking off-panel about it) is more correctly called Cueball than any of the others. But typically the one named Cueball is either the protagonist or the one with the interesting parts, or the one with the punch line. In this comic it would be the e-mac Cueball, as he makes the butterfly guy loose out to e-mac. It may thus be OK to list him as Cueball, and the others as something else. So I changed that some time ago in the explanation, and transcript. But then I also made sure that it was clear that the other guys also looks like Cueball. --Kynde (talk) 21:20, 20 December 2015 (UTC)

Real Programmers use MS Paint: http://i.imgur.com/QlGpd.gif Luc (talk) 01:40, 3 July 2016 (UTC)

I don't know which came first but this quote reminded me of this comic http://bash.org/?6130172.69.34.228 04:20, 3 May 2021 (UTC)

It occurs to me that, during the Apollo space program, the core-rope memory which contained the program code for the ship's onboard guidance computer was, quite literally, hand-woven. While it was non-magnetic, a needle was used to thread a single strand of wire through a frame containing an array of ferrite cores. Similar to then-conventional core memory, except that wires selectively did or did not pass through any given core to permanently set their state as 0 or 1. - Thraddax, 02 June 2021.

- That's what I interpreted the needle as referring to initially. — 172.69.165.23 12:17, 4 October 2023 (UTC)

vi but confused the two. Beanie talk 13:01, 6 September 2022 (UTC)