Difference between revisions of "2971: Celestial Event"

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Conversion of "days" and "months" to fractional years, required for conservation of units in the equation, is ambiguous as presented due to the leap year phenomenon and the inconsistent number of days in a month. Differing values for these fractional years yield a range of frequency solutions between 4.2 and 4.4 billion years. If the value for days in a year is given as 365.25 (the mean value for all years, ignoring infrequent additional 'leap year' corrections), as in the first term of the equation ((20/365.25)/11), and the mean value for days in two months is given as 60.9 as in the second term ((60.9/365.25)/50), the result is 4.2995 *10^9 years. On top of that, the length of the day {{w|Earth's rotation#Ancient observations|may change significantly}} (and also, potentially, {{w|Stability of the Solar System|the year}}), which would conceivably change the observable frequencies (and thus the length and offset of the compounded frequency of coincidence) quite a lot over the lifetime of the 'now'-calculated interval of recurrance. | Conversion of "days" and "months" to fractional years, required for conservation of units in the equation, is ambiguous as presented due to the leap year phenomenon and the inconsistent number of days in a month. Differing values for these fractional years yield a range of frequency solutions between 4.2 and 4.4 billion years. If the value for days in a year is given as 365.25 (the mean value for all years, ignoring infrequent additional 'leap year' corrections), as in the first term of the equation ((20/365.25)/11), and the mean value for days in two months is given as 60.9 as in the second term ((60.9/365.25)/50), the result is 4.2995 *10^9 years. On top of that, the length of the day {{w|Earth's rotation#Ancient observations|may change significantly}} (and also, potentially, {{w|Stability of the Solar System|the year}}), which would conceivably change the observable frequencies (and thus the length and offset of the compounded frequency of coincidence) quite a lot over the lifetime of the 'now'-calculated interval of recurrance. | ||

| − | In the title text, Randall mentioned 13-year cicadas. Massachusetts is near the northern limit of {{w|Periodical_cicadas|<em>Magicicada</em>}} distribution, and only one 17-year brood is established there (and not in Cambridge, MA). In other parts of the US, a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood emerged during 2024, an event that only happens once every 13x17 = 221 years. This caused a lot of noise and double the amount of dead cicadas after they had mated. Randall wondered whether it would be possible to get a brood of 13 year cicadas started near his home. In that | + | In the title text, Randall mentioned 13-year cicadas. Massachusetts is near the northern limit of {{w|Periodical_cicadas|<em>Magicicada</em>}} distribution, and only one 17-year brood is established there (and not in Cambridge, MA). In other parts of the US, a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood emerged during 2024, an event that only happens once every 13x17 = 221 years. This caused a lot of noise and double the amount of dead cicadas after they had mated. Randall wondered whether it would be possible to get a brood of 13 year cicadas started near his home. |

| + | |||

| + | Earth's oceans may evaporate in about one billion years<ref>https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/12/131216142310.htm</ref>. In order to beat that, we need to better our odds. Using 13-year cicadas in our calculations reduces the average interval between events to 3.29 billion years. We can lower that further by hoping that we'll have clear skies by then (who knows, we might get good enough at manipulating weather that we can *make* it happen. That gives us an average interval between events of about 1.6 billion years. Since the remaining events are cyclical, there's a larger than 50% chance that one such event may happen within a billion years, therefore beating ocean evaporation. Of course, cicadas may not last that long.<sup>[<em><span style="color:#1144aa !important; ">baseless conjecture</span></em>]</sup> <sup>[<em><span style="color:#1144aa !important; ">trust the cicadas</span></em>]</sup> | ||

| + | |||

==Transcript== | ==Transcript== | ||

Revision as of 00:08, 14 August 2024

| Celestial Event |

Title text: If we can get a brood of 13-year cicadas going, we might have a chance at making this happen before the oceans evaporate under the expanding sun. |

Explanation

| This is one of 74 incomplete explanations: Created by a CURSED SHOP THAT APPEARS EVERY FOUR POINT THREE BILLION YEARS - Please change this comment when editing this page. Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

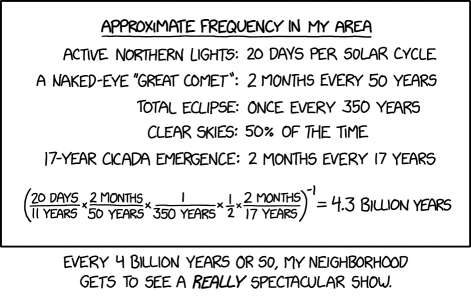

Randall has often obsessed over celestial events he wishes to see, and here lists three of these in this comic, hence the title. Recently there have been two total solar eclipses in the US (2017 and 2024), so that has been ticked off his bucket list. And there have been northern lights this year far down into the mainland US. So it is likely he has also seen those. Whether or not he has seen a comet visible to the naked eye is not known, but there have been some candidates in his lifetime.

The next two on the list are not celestial events, but the lack of cloud cover is relevant in order to see the first three. Finally, he mentions the emergence of 17-year cicadas which occurred most recently in the midwestern US in 2024 and in the eastern US in 2021.

An extra special celestial event would be to see all the three first things at the same time during a 17-year cicada event. Northern lights and a comet can only be seen during the night, except during a total solar eclipse where they could be visible for the few minutes of totality. (However, it rarely gets really dark during totality, and it is so short that night vision cannot be achieved before the totality is over.)

This joke of the comic comes from Randall multiplying the fraction of time that these selected classes of events occur over a particular location on the Earth's surface, in this case, Cambridge, Massachusetts, where the cartoonist was living when this comic was published. The resulting product is the expected frequency that all of them would occur at the same time at that location. The value he calculates is once every 4.3 billion years. This is in the same ballpark as the current age of the Earth, about 4.5 billion years.

The calculation itself is not going to be accurate, which is likely part of the joke. Multiplying probabilities only works for random variables that are entirely independent. If nothing else, orbits are (luckily[citation needed]) not random.[citation needed] It also requires that all of the probabilities remain constant over time. In reality, cicadas will not exist for very long compared to the time scale, since Earth will become uninhabitable to complex life within a billion years' time and all life will be extinct within 4 billion years. Also, the moon is moving away from Earth, and total solar eclipses will cease to occur in about 600 million years. Luckily, this is not the time that you are always going to wait, merely the (usual) period between one occurance and the next. A person starting to wait at a random point in the cycle, and no knowing anything else, would on average only have to wait half the time. (If very lucky, it could happen tomorrow, as it hypothetically might have done a bit over four billion years ago; if unlucky, it would indeed be slightly more than four billion years, having most recently happened yesterday; if very unlucky, the frequencies are slightly less defined, do not actually align as expected for the next conclusion of the cycle and additional billions of years need to be waited until the next example when it 'might' indeed occur as anticipated. Finally, if extremely unlucky, you will never get a clear sky. Ever.

Conversion of "days" and "months" to fractional years, required for conservation of units in the equation, is ambiguous as presented due to the leap year phenomenon and the inconsistent number of days in a month. Differing values for these fractional years yield a range of frequency solutions between 4.2 and 4.4 billion years. If the value for days in a year is given as 365.25 (the mean value for all years, ignoring infrequent additional 'leap year' corrections), as in the first term of the equation ((20/365.25)/11), and the mean value for days in two months is given as 60.9 as in the second term ((60.9/365.25)/50), the result is 4.2995 *10^9 years. On top of that, the length of the day may change significantly (and also, potentially, the year), which would conceivably change the observable frequencies (and thus the length and offset of the compounded frequency of coincidence) quite a lot over the lifetime of the 'now'-calculated interval of recurrance.

In the title text, Randall mentioned 13-year cicadas. Massachusetts is near the northern limit of Magicicada distribution, and only one 17-year brood is established there (and not in Cambridge, MA). In other parts of the US, a 13-year brood and a 17-year brood emerged during 2024, an event that only happens once every 13x17 = 221 years. This caused a lot of noise and double the amount of dead cicadas after they had mated. Randall wondered whether it would be possible to get a brood of 13 year cicadas started near his home.

Earth's oceans may evaporate in about one billion years[1]. In order to beat that, we need to better our odds. Using 13-year cicadas in our calculations reduces the average interval between events to 3.29 billion years. We can lower that further by hoping that we'll have clear skies by then (who knows, we might get good enough at manipulating weather that we can *make* it happen. That gives us an average interval between events of about 1.6 billion years. Since the remaining events are cyclical, there's a larger than 50% chance that one such event may happen within a billion years, therefore beating ocean evaporation. Of course, cicadas may not last that long.[baseless conjecture] [trust the cicadas]

Transcript

| This is one of 44 incomplete transcripts: Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

- Approximate frequency in my area

- Active northern lights: 20 days per solar cycle

- A naked-eye "Great Comet": 2 months every 50 years

- Total eclipse: once every 350 years

- Clear skies: 50% of the time

- 17-year cicada emergence: 2 months every 17 years

opening bracket

20 days over 11 years multiplied by

2 months over 50 years multiplied by

1 over 350 years multiplied by

one half multiplied by

2 months over 17 years

closing bracket to the power of -1

equals 4.3 billion years

- [Caption below the panel:]

- Every 4 billion years or so, my neighborhood gets to see a really spectacular show.

Discussion

Unfortunately, this calculation doesn't account for the eventual end of total solar eclipses due to the tidal recession of the moon. 172.69.246.142 05:31, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- This is a great comment! Very much like something Randall would have written for title text. 172.71.146.49 05:58, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- Agreed! Also, it seems like the article should have a footnote or separate section going full Randall, "Based only on the data given in this cartoon, what is the possible range of Randall Munroe's home location?" --AnnapolisKen (talk) 18:21, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- Speculating about people's addresses online is generally frowned upon, in court if nowhere else. 172.68.14.183 00:50, 14 August 2024 (UTC)

- As in the original post, the humor in it is that the quest would be effectively useless, right? I mean probably the best data point would be that it's in an area where 17-year cicadas brood. I'm not sure any other data could narrow it down beyond that. --AnnapolisKen (talk) 14:05, 15 August 2024 (UTC)

- Speculating about people's addresses online is generally frowned upon, in court if nowhere else. 172.68.14.183 00:50, 14 August 2024 (UTC)

- Agreed! Also, it seems like the article should have a footnote or separate section going full Randall, "Based only on the data given in this cartoon, what is the possible range of Randall Munroe's home location?" --AnnapolisKen (talk) 18:21, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

Are all of these events really statistically independent or are e.g. active northern lights and cicada mergence more or less likely to happen at the same time of the year? 172.68.194.201 (talk) 06:15, 13 August 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Ooh, great question. It turns out cicadas only emerge in warm weather, particularly in summer, and

you can only see the northern lights in winter. That's bad news for us, our superevent might never happen. 172.69.90.3 01:03, 14 August 2024 (UTC) — edit: oops, I got it wrong. It turns out you can see them all year round. They're actually happening right now in some parts of the US.

This comic was published the same night that saw both the Perseids meteor shower and an unusually strong northern lights. Strangely, the omission of meteor showers in Randall's account of Celestial Events suggests that this is a coincidence. Mumiemonstret (talk) 11:43, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

One eclipse every 350 years is not "1/350" - that would imply the eclipse lasted the whole year. The numerator unit should be a minute or so, vastly changing the result. 172.70.39.114 (talk) 13:16, 13 August 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Actually, thanks to unit cancelation, Randall's math checks out. I really really feel that it shouldn't, but it does. It's 1/350 years because what you're calculating is "once every X years". It doesn't actually matter how long an eclipse lasts, so long as it's a sufficiently small amount of time so as to be treated as a single point in time. "When that point in time happens, how frequently will those other things be happening?". You can give that answer in days, years, or whatever other unit of time you prefer. Since we're giving it in years, the number we need is "how often (am eclipse occurs) each year" - 172.68.14.185 23:32, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- Yes, I came back to correct myself on this after more reflection. The implied unit is Event and this is the only such non-dimentionless factor. 108.162.245.186 (talk) 23:40, 13 August 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- Tru dat, as are the comments regarding changes over time in eclipse parameters and the effects of time approximations. However, if we let "4 minutes" be the mean time of totality for an eclipse, and insert that term (for the record, 7.6E-06) for "1" in "1/350", the equation's solution becomes 4E+14, orders of magnitude greater than the age of the universe and, IIRC, well into its projected "heat death". The joke appears to reside in the proximity of Randall's solution to the commonly-accepted age of the Earth, making the solution "just possible". More "accurate" solutions would not be funny, and we would not have seen this comic.162.158.41.227 17:11, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- In the "1/350years", I took it to mean that the unitless "1" represented a day (within which an eclipse occurs, and across this period would also extend the various other conditions). By treating all other unit-laden values as correctly converted to the number in the term of days (and back-converted to the 'more convenient' billions of years for the result), it probably ...not that I did the mathematics to check this... comes out as Randall suggests.

- If, indeed, the length of an (average, as of Earth's current configuration) eclipse, and all other values were understood as proxies for the "number of eclipse-lengths" (except for the uncloudy sky fraction, which is always a unitless half through cancelling out) then you might end up with a result that's different. But the way to check this is to accept the answer (in billions of years) and all the others with time-lengths (respectively) and work out the rough united-length of the "1" by to identify what unit would best fit that. But I leave that to whoever really wants to dive that deep into it, as the next logical step beyond mere attempted pedantry. 172.68.205.164 20:22, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- Every other 2 billion years, on days when it's cloudy or raining, the neighborhood doesn't get to see the spectacular show. 162.158.154.98 19:19, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

There are competing factors with regard to the eclipse. Obviously total eclipses don't last for an entire year [citation needed], but in the distant past when the Moon was significantly closer, they occurred much more frequently than once every 350 years. Far enough back, the moon was significantly larger in the sky and orbited much more rapidly making total solar eclipses a much more common event (even if nobody with eyes was around to see). Using constants for probabilities when things have significant variation is tricky. Galeindfal (talk) 14:26, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

- I just added (without having seen the above comment) something that deals with that. Actually, that and the way that the 'beat frequency' may just fail to create an all-effect maximum due to it not being a strictly repeating frequency (if you have an eclipse on one date, with a "1 event in 350 years" calculation for your location/latitude, it doesn't preclude more than one per 350 years or two separated by vastly more than 350 years - though still likely to get "N+1" eclipses over any given 350xN year period for higher Ns).

- If it's a combinatorial experience of fully periodic frquencies (such as with 1331: Frequency then you can be precise over the beat-frequency, but any statistical perturbation can make a 'full hit' into a 'not-fully hit' event quite easily. At its simplest, though the chances of any given day (or useful fraction of a day) of being clear-skied may be 50%, it's not as simple to say "yesterday was cloudy, tomorrow will be clear", or vice-versa. Perhaps slightly more useful to say that than "the year just gone had no clouds, so this year will be full of them" or imagining that every second you could glance up and see "clouds...", "no clouds...", "clouds...", "no clouds...". The meteorological 'calculations' would never be anywhere near as simple as even the (future-trends modified) far-future predictability of the astronomical effects. The biologist might be able to be reasonably sure that the season-locked emergence of a given cicada brood will actually continue to satisfy their contribution to the calculation for much longer than the weatherman might (though they'd have to admit to the high probability that an ecological upset would flat out end any chances before any of the other forecasts become too hazy to rely upon).

- So the changing of frequencies over the time of the 9calculated) meta-beat's recurrance will make for an compoundedly-chaotic 'actual' meta-beat (assuming it ever completes). This includes the possibility that it actually re-meshes its individual occurances into an actually far more frequent coincidence (two consecutive cicada emergences could end up both being accompanied by all the other requirements). Depends how much you take at face-value, rather than as a rough and ready 'approximation' for fun-and-non-profit... 172.68.205.164 20:22, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

The adjustment due to leap years is far dwarfed by the approximate nature of "20 days" and "2 months" in some of the events. Barmar (talk) 15:06, 13 August 2024 (UTC)

Don't know how it could be calculated in, but there's a fundamental conflict between the solar eclipse and aurora borealis. Solar eclipses are only visible during the day [citation needed], but the aurorae aren't symmetrical around the poles and drag further equator-ward on the night side of the planet. So the occurrences of Northern lights that would reach to Boston latitudes on the *day side* of the planet so as to be visible during a solar eclipse would be much, much rarer (closer to Carrington-event rarity, currently pitched at once every 100 to 1000 years instead of the 11 Randall used, but even then it'd have to be a particularly strong event). 172.70.230.142 13:34, 14 August 2024 (UTC)

If he had included all these events happening on a Tuesday or a Thursday then we're getting close to 1 every 14 billion years. A time which everyone's neighbourhoods had a really big show. Kev (talk) 02:36, 15 August 2024 (UTC)

Someone has to say it. The explanation is so long and convoluted that it serves substantially more to confuse than to explain. Someone please edit it mercilessly. 172.69.33.62 05:14, 15 August 2024 (UTC)

- I bit the bullet. I'm sure I left some important stuff out, but more sure I deleted more unimportant stuff. 172.71.146.211 06:24, 15 August 2024 (UTC)

But the question is, will the superevent coincide with the release of an xkcd comic? -- RadiantRainwing (talk) 23:01, 16 August 2024 (please sign your comments with ~~~~)

- a blue supermoon could be seen on monday, which is an xkcd upload day, and that happens every 10 years… 42.book.addict (talk) 23:58, 22 August 2024 (UTC)

I may be nitpicking, but the event happening each 50 years and one happening each 350 years are mutually paraller, as in either they happen both every 350 years, or they never happen together at all. You can and possibly should argue that it's not true due to "imprecision with which the periods are recorded", but the proper way to count how often do ALL events occur, is not to count the independent chance over time, but the event offsets from one another, with easiest math if we start from the rarest one.--162.158.172.188 23:52, 22 August 2024 (UTC)

- I think you're talking of applying the Least Common Multiple (the lowest value that is an integer multiple of all individual integer values). Though the answer to that (for all element pairs that don't already have a 1:n relation) can rely upon the base unit involved. Something that's every four months with something every seven months coincides every twenty-eight months. But every year will have (at least one of) each happening. And, as you point out, the situation may never coincide at the day level (the first happens every first week of the given month, the second happens on the third of its own months, or one only happens on the nearest Tuesday and the other on the Wednesday).

- What we have here is the combined product, which can be divided by the Highest Common Factor to give the LCM, but only once we agree into what we're factoring (by year, day, hour, the length of a typical eclipse, the second...), and then deal with issues of mutually-missing pairs of 'matchable but offset' cycles. 172.71.26.46 04:31, 23 August 2024 (UTC)

Now calculate the odds that a science fiction story will be published that places such an occurrence in our current timeframe. These Are Not The Comments You Are Looking For (talk) 01:09, 26 August 2024 (UTC)

Can we have a category for comics like these that (ab)use dimensional analysis and unit cancellation? 172.71.8.40 02:23, 27 November 2024 (UTC)