Difference between revisions of "3200: Chemical Formula"

(→Transcript: cats) |

(state why it's unknown) |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

* B<sub>10<sup>71</sup></sub> - One hundred duovigintillion boron atoms | * B<sub>10<sup>71</sup></sub> - One hundred duovigintillion boron atoms | ||

* Ba<sub>10<sup>70</sup></sub> - Ten duovigintillion barium atoms | * Ba<sub>10<sup>70</sup></sub> - Ten duovigintillion barium atoms | ||

| − | * Be - An unknown quantity of beryllium atoms | + | * Be (cut off by the edge of the comic) - An unknown quantity of beryllium atoms |

The matter originally created in the Big Bang was unbound protons and neutrons. In the first few minutes, {{w|Big Bang nucleosynthesis|some of these combined to form lightweight nuclei}}, but most remained as protons, i.e. the nuclei of hydrogen atoms. Other, more complex atoms formed later as a result of {{w|stellar nucleosynthesis}}, up to atomic mass 56. Still more massive nuclei have been formed via {{w|supernova nucleosynthesis}}. Although the proportions of these atoms depend in a complex way on the fusion processes involved, and on the stabilities of those nuclei, the most massive atoms are generally both less favored to form and short-lived, so their elemental abundances in the universe are very small. As shown above, the number of americium (Am) atoms is much smaller than those of any other element in the visible part of the "formula". There are slightly fewer atoms of americium in the entire universe than the total number of atoms of hydrogen and oxygen in 1.0 L of liquid water. | The matter originally created in the Big Bang was unbound protons and neutrons. In the first few minutes, {{w|Big Bang nucleosynthesis|some of these combined to form lightweight nuclei}}, but most remained as protons, i.e. the nuclei of hydrogen atoms. Other, more complex atoms formed later as a result of {{w|stellar nucleosynthesis}}, up to atomic mass 56. Still more massive nuclei have been formed via {{w|supernova nucleosynthesis}}. Although the proportions of these atoms depend in a complex way on the fusion processes involved, and on the stabilities of those nuclei, the most massive atoms are generally both less favored to form and short-lived, so their elemental abundances in the universe are very small. As shown above, the number of americium (Am) atoms is much smaller than those of any other element in the visible part of the "formula". There are slightly fewer atoms of americium in the entire universe than the total number of atoms of hydrogen and oxygen in 1.0 L of liquid water. | ||

Revision as of 23:22, 28 January 2026

| Chemical Formula |

Title text: Some of the atoms in the molecule are very weakly bound. |

Explanation

| This is one of 60 incomplete explanations: This page was created by the carbon in the universe . Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

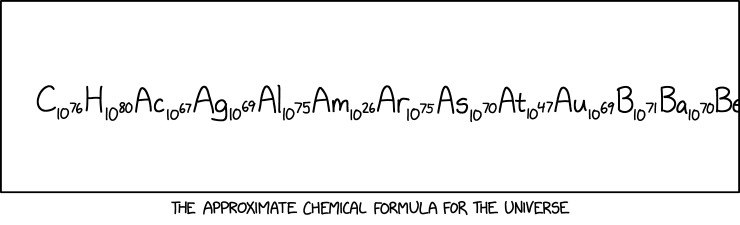

The supposed "chemical formula for the universe" merely lists the numbers of atoms of each element. As is common practice for real compounds that contain organic structures or substructures, the numbers of atoms of carbon and hydrogen are listed before all of the others; the others are listed in alphabetical order. There are estimated to be 1080 atoms of hydrogen (H), by far the most common element in the universe. The next most common element, helium (He), is a long way to the right in the list, and out of view, but would be about a third as many as the hydrogens.

These numbers are large, but they are not nameless. Using the short scale, these numbers can be described as:

- C1076 - Ten quattuorvigintillion carbon atoms

- H1080 - One hundred quinvigintillion hydrogen atoms

- Ac1067 - Ten unvigintillion actinium atoms

- Ag1069 - One duovigintillion silver atoms

- Al1075 - One quattuorvigintillion aluminium atoms

- Am1026 - One hundred septillion americium atoms

- Ar1075 - One quattuorvigintillion argon atoms

- As1070 - Ten duovigintillion arsenic atoms

- At1047 - One hundred quattuordecillion astatine atoms

- Au1069 - One duovigintillion gold atoms

- B1071 - One hundred duovigintillion boron atoms

- Ba1070 - Ten duovigintillion barium atoms

- Be (cut off by the edge of the comic) - An unknown quantity of beryllium atoms

The matter originally created in the Big Bang was unbound protons and neutrons. In the first few minutes, some of these combined to form lightweight nuclei, but most remained as protons, i.e. the nuclei of hydrogen atoms. Other, more complex atoms formed later as a result of stellar nucleosynthesis, up to atomic mass 56. Still more massive nuclei have been formed via supernova nucleosynthesis. Although the proportions of these atoms depend in a complex way on the fusion processes involved, and on the stabilities of those nuclei, the most massive atoms are generally both less favored to form and short-lived, so their elemental abundances in the universe are very small. As shown above, the number of americium (Am) atoms is much smaller than those of any other element in the visible part of the "formula". There are slightly fewer atoms of americium in the entire universe than the total number of atoms of hydrogen and oxygen in 1.0 L of liquid water.

This may be poking some fun at the relative usefulness (or rather, uselessness) of chemical formulas for large organic molecules. While it is a useful concept for teaching people about chemistry and balancing equations, and it was useful in the early days of chemistry to try to categorize and learn about molecules via stoichiometry - it does not give much useful information. For example even the simple formula C11H15NO2 has 302 registered isomers. Many of them are NOT good to eat.[citation needed]

Transcript

| This is one of 40 incomplete transcripts: Don't remove this notice too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

- [A long panel with a chemical formula trailing off the right side]

- C1076 H1080 Ac1067 Ag1069 Al1075 Am1026 Ar1075 As1070 At1047 Au1069 B1071 Ba1070 Be

- [Caption below the panel:] The approximate chemical formula for the universe

Discussion

I'm disappointed that it wasn't scrollable. 2001:41D0:8:5062:0:0:0:1 20:20, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

- +1 And funny to think that the universe contains less than a few hundred mol of Americium. --2001:16B8:CC03:E100:8552:6543:7CF4:9AE7 20:57, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

If anyone's interested in an accessible resource for getting more data like this, may I suggest https://ptable.com/#Properties/Abundance/Universe (which I believe derives data from IUPAC sources) Dextrous Fred (talk) 20:37, 28 January 2026 (UTC) surprised to see so much Astatine, he himself declared, that stuff doesnt want to exist so I expected yet a few powers of ten less

This does make me curious: how would neutronium be represented in a chemical formula? Or would it be? My impression is it kind of exists 'outside' of chemistry... -Kalil 147.81.60.76 21:12, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

- Neutron stars would be represented with n with various mass numbers. And there are no more than 1 mmol (6.02214076×1020) of neutron stars. 2001:4C4E:1C09:EC00:7932:264E:A9E0:8ED0 21:38, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

What about adding mass numbers? For example, most of the hydrogen is 1H, with small amounts of 2H and trace amounts of 3H. 2001:4C4E:1C09:EC00:7932:264E:A9E0:8ED0 21:38, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

- Oh look, it's the 3200th comic! Yay I guess! --DollarStoreBa'alConverse 22:46, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

An unregistered user (198.48.180.159) added a note that the chemical formula "C11H15NO2" (i.e. C11H15NO2) "has 302 registered isomers". I don't know the source for that number or where those isomers are registered. (It's the formula for MDMA, which is, as noted, "not good to eat".) Would that be the CAS registry? BunsenH (talk) 23:20, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

- Don't know if this works, but here's a site that does immediately return 302 compounds: https://pubchemlite.lcsb.uni.lu/compounds?query=C11H15NO2 8.17.60.225 04:19, 29 January 2026 (UTC)

10^26 atoms of americium is about 40 kg. But it looks like humans produced tons of americium: https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/np_237_and_americium.pdf . If there are other civilizations in the observable Universe, then the amount of americium in the Universe is even higher. So I guess the formula counts only naturally produced elements. But even then it seems underestimated. Alexei Kopylov (talk) 23:45, 28 January 2026 (UTC)

- In everything that I've checked (I expanded the "list of names" into a table), I could not discover any universal quantity of americium that was close to Randall's apparent source. Can't exclude the possibility that artificially nucleogenesis played a part in his figures (while mine are from how much was created 'naturally'), but I've just had to go along with it being a completely wrong figure (for the ultimate universal ranking). Much as boron might be given slightly mismagnituded.

- However, if anyone thinks they have the same source that led to the comic's values (and can reconfirm beryllium's estimated order of magnitude, which is the only reason I decided to start on compiling this amount of extended data, which is actually for all 118 humanly known elements), then you're welcome to correct anything that I left in an incorrect state. 81.179.199.253 00:16, 29 January 2026 (UTC)

...but what if you had a mole of universes?

- In the explanation, towards the end of the formula for the universe, it says U₁₀². Would that mean that there are only about 100 uranium atoms in the whole universe? That seems way too low. Did the explainer confuse the powers of 10 with rankings (in reverse)? --208.59.176.206 03:48, 29 January 2026 (UTC)

- I'm not sure where the error came from, but about half the numbers are drastically too low. Remember, a mole is 6.02*10^23. 174.94.104.215 05:34, 29 January 2026 (UTC)

- Fixed. The powers were just in descending order, one by one. The current values reflect the actual amounts, give or take one or two orders of magnitude. --1234231587678 (talk) 06:04, 29 January 2026 (UTC)