Difference between revisions of "2857: Rebuttals"

Liv2splain (talk | contribs) (→Explanation: more likely for rematic, per talk) |

Liv2splain (talk | contribs) (→Explanation: merge paragraphs on same topic) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Overall, the comic offers a funny yet deep look at how scientists think and argue. It shows that in science, people often change their minds between new discoveries and what most people already believe. The character Cueball represents scientists and explains this complicated process. The comic starts by showing how scientists sometimes don't like new ideas if they don't fit with what most people already think. This happens even if the new ideas might be true. It shows a kind of tug-of-war in science: sometimes scientists are more open to new things, and other times they stick to old ideas. Also, the comic says that when people don't agree with the usual thinking, they might also ignore new facts that don't match their own ideas. Everyone in science might miss something important because they're too focused on their own beliefs. | Overall, the comic offers a funny yet deep look at how scientists think and argue. It shows that in science, people often change their minds between new discoveries and what most people already believe. The character Cueball represents scientists and explains this complicated process. The comic starts by showing how scientists sometimes don't like new ideas if they don't fit with what most people already think. This happens even if the new ideas might be true. It shows a kind of tug-of-war in science: sometimes scientists are more open to new things, and other times they stick to old ideas. Also, the comic says that when people don't agree with the usual thinking, they might also ignore new facts that don't match their own ideas. Everyone in science might miss something important because they're too focused on their own beliefs. | ||

| − | Cueball's words in the comic are like peeling an onion in science, showing different layers of arguments and disagreements. The comic suggests that sometimes, even when scientists are trying to move away from old ideas, they might not notice new facts that actually support these old ideas. Cueball seems to agree with this view but then starts to say "however," like he's going to give a ''rebuttal'' opinion or explain the situation in a new way. | + | Cueball's words in the comic are like peeling an onion in science, showing different layers of arguments and disagreements. The comic suggests that sometimes, even when scientists are trying to move away from old ideas, they might not notice new facts that actually support these old ideas. Cueball seems to agree with this view but then starts to say "however," like he's going to give a ''rebuttal'' opinion or explain the situation in a new way. Maybe Cueball will offer a new explanation about how scientists argue or say that all sides in science have good points but sometimes misunderstand each other. This could mean that the debates in science are not as simple as they seem and that everyone might have a piece of the truth. |

| − | |||

| − | Maybe Cueball will offer a new explanation about how scientists argue or say that all sides in science have good points but sometimes misunderstand each other. This could mean that the debates in science are not as simple as they seem and that everyone might have a piece of the truth. | ||

The title text serves as an extension of this theme, offering a linguistic maze that mirrors the complexity and sometimes absurdity of academic discourse. It whimsically encapsulates how a challenge to mainstream thought can solidify into its own dogma, necessitating further revisionist waves, in an endless cycle of intellectual evolution and revolution. This self-referential loop wittily underscores {{w|Thomas Kuhn}}'s notion of the '{{w|Structure of Scientific Revolutions}},' suggesting that what is considered revolutionary at one time may become the very dogma that future revolutions seek to overturn. The title text delights in linguistic acrobatics, stringing together a series of portmanteau and near-repetitive phrases that dance on the tongue with the finesse of a verbal gymnast. "Mainstream dogma" suggests widely accepted beliefs, but it swiftly mutates into "dogmatic revisionism," a playful jab at the stubborn insistence on reforming the norm. This revisionism doesn't just adjust the current; it becomes "mainstream dogmatism" in its own right, a new orthodoxy birthed from the rebellion. And then, with a flourish, it yields to an even more whimsically coined "rematic mainvisionist dogstream," a hilarious {{w|spoonerism}} that could leave even the most loquacious academic's head spinning. This nonsensical cascade mocks the sometimes pretentious and convoluted language that can plague scholarly communication, turning serious dialogue into a merry-go-round of terms that are as circular in progression as they are in logic. | The title text serves as an extension of this theme, offering a linguistic maze that mirrors the complexity and sometimes absurdity of academic discourse. It whimsically encapsulates how a challenge to mainstream thought can solidify into its own dogma, necessitating further revisionist waves, in an endless cycle of intellectual evolution and revolution. This self-referential loop wittily underscores {{w|Thomas Kuhn}}'s notion of the '{{w|Structure of Scientific Revolutions}},' suggesting that what is considered revolutionary at one time may become the very dogma that future revolutions seek to overturn. The title text delights in linguistic acrobatics, stringing together a series of portmanteau and near-repetitive phrases that dance on the tongue with the finesse of a verbal gymnast. "Mainstream dogma" suggests widely accepted beliefs, but it swiftly mutates into "dogmatic revisionism," a playful jab at the stubborn insistence on reforming the norm. This revisionism doesn't just adjust the current; it becomes "mainstream dogmatism" in its own right, a new orthodoxy birthed from the rebellion. And then, with a flourish, it yields to an even more whimsically coined "rematic mainvisionist dogstream," a hilarious {{w|spoonerism}} that could leave even the most loquacious academic's head spinning. This nonsensical cascade mocks the sometimes pretentious and convoluted language that can plague scholarly communication, turning serious dialogue into a merry-go-round of terms that are as circular in progression as they are in logic. | ||

Revision as of 22:07, 21 November 2023

| Rebuttals |

Title text: The mainstream dogma sparked a wave of dogmatic revisionism, and this revisionist mainstream dogmatism has now given way to a more rematic mainvisionist dogstream. |

Explanation

| This is one of 60 incomplete explanations: Created by a REMATIC DOGSTREAM. Do NOT delete this tag too soon. If you can fix this issue, edit the page! |

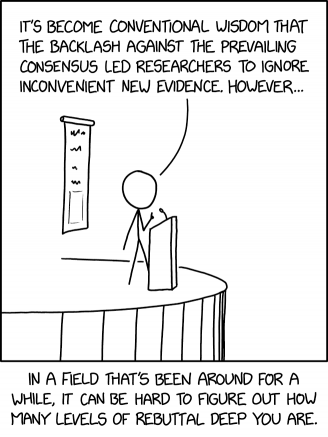

This comic provides a satirical take on the intricate layers of scientific critique and consensus. Cueball stands as a representative of the scientific community, addressing the audience with a statement that encapsulates the recursive nature of scientific debate. The comic touches on the propensity within the scientific fields to oscillate between embracing new evidence and adhering to established consensus. It reflects on the inclination to reject new findings not because they lack merit, but because they conflict with the prevailing theories that have weathered previous scrutiny and dissent. Here is what Cueball is saying, simplified:

"Most of us assume the following: That when a lot of people didn't agree with what most experts said, those experts stopped paying attention to new facts that didn't fit their ideas. But actually..."

Overall, the comic offers a funny yet deep look at how scientists think and argue. It shows that in science, people often change their minds between new discoveries and what most people already believe. The character Cueball represents scientists and explains this complicated process. The comic starts by showing how scientists sometimes don't like new ideas if they don't fit with what most people already think. This happens even if the new ideas might be true. It shows a kind of tug-of-war in science: sometimes scientists are more open to new things, and other times they stick to old ideas. Also, the comic says that when people don't agree with the usual thinking, they might also ignore new facts that don't match their own ideas. Everyone in science might miss something important because they're too focused on their own beliefs.

Cueball's words in the comic are like peeling an onion in science, showing different layers of arguments and disagreements. The comic suggests that sometimes, even when scientists are trying to move away from old ideas, they might not notice new facts that actually support these old ideas. Cueball seems to agree with this view but then starts to say "however," like he's going to give a rebuttal opinion or explain the situation in a new way. Maybe Cueball will offer a new explanation about how scientists argue or say that all sides in science have good points but sometimes misunderstand each other. This could mean that the debates in science are not as simple as they seem and that everyone might have a piece of the truth.

The title text serves as an extension of this theme, offering a linguistic maze that mirrors the complexity and sometimes absurdity of academic discourse. It whimsically encapsulates how a challenge to mainstream thought can solidify into its own dogma, necessitating further revisionist waves, in an endless cycle of intellectual evolution and revolution. This self-referential loop wittily underscores Thomas Kuhn's notion of the 'Structure of Scientific Revolutions,' suggesting that what is considered revolutionary at one time may become the very dogma that future revolutions seek to overturn. The title text delights in linguistic acrobatics, stringing together a series of portmanteau and near-repetitive phrases that dance on the tongue with the finesse of a verbal gymnast. "Mainstream dogma" suggests widely accepted beliefs, but it swiftly mutates into "dogmatic revisionism," a playful jab at the stubborn insistence on reforming the norm. This revisionism doesn't just adjust the current; it becomes "mainstream dogmatism" in its own right, a new orthodoxy birthed from the rebellion. And then, with a flourish, it yields to an even more whimsically coined "rematic mainvisionist dogstream," a hilarious spoonerism that could leave even the most loquacious academic's head spinning. This nonsensical cascade mocks the sometimes pretentious and convoluted language that can plague scholarly communication, turning serious dialogue into a merry-go-round of terms that are as circular in progression as they are in logic.

This nonsense phrase may also be mocking the way in which, when you get this many layers deep in waves of consensus and counter-consensus, all these terms start to lose any real meaning, and become mere empty labels to be thrown around as terms of deprecation or abuse between the competing factions.

| Title text term | (Possible) meaning | Nature of the term |

|---|---|---|

| Mainstream dogma | The popular and currently unchallenged set of beliefs that comfortably flow with the academic current. | Real |

| Dogmatic revisionism | The stubborn insistence on changing established views, with a religious zeal for rewriting the scholarly scripture. | Unlikely combination of real words |

| Revisionist mainstream | Once the avant-garde, now the new normal; the rebel ideas that have become the establishment. | Unlikely combination of real words |

| Dogmatism | An unshakable adherence to the new creed, now fervently preached as the one true academic gospel. | Real |

| Rematic | Revisionist dogma, or perhaps related to "remake" or "remix," implying a recycled, refurbished set of ideas in vogue once more. | Not a real word |

| Mainvisionist | A visionary yet mainstream adherent, with sights set on steering the scholarly ship into familiar waters. | Not a real word |

| Dogstream | The current of thought that flows doggedly along, resistant to change and comfortably narrow. Taken literally, a river of dogs. | Not a real word |

| Mainvisionist dogstream | The dominant narrative that's been revised so often, it's hard to distinguish from its own parody. | Not real words |

Transcript

- [Cueball, hand raised with a finger held up, stands behind a lectern on a high podium speaking into a microphone on the lectern. Behind him is a banner, with four lines of illegible writing above a (blank) picture at the bottom.]

- Cueball: It's become conventional wisdom that the backlash against the prevailing consensus led researchers to ignore inconvenient new evidence. However...

- [Caption below the panel:]

- In a field that's been around for a while, it can be hard to figure out how many levels of rebuttal deep you are.

Discussion

Ok, so...

- "...new evidence" (yes, possibly we can start with "...evidence", but let's start with the first contrarianism).

- "...inconvenient..." (so there's something we're saying is wrong with that new evidence?)

- "...led researchers to ignore..." (maybe could fold in with the inconvenience, but arguably ignoring is a 'third way' step in sidelining it, not even disagreeing)

- "...the prevailing consensus..." (another layer of implied position-taking where there is something to disagree with)

- "...the backlash against..." (to which others firmly took up the contrary)

- "It's become conventional wisdom that..." (and this is a counter-contrary perspective)

- "However..." ("...and I, for one, think that they're wrong about the whole thing!")

...well, by a very quick and dirty deconstruction. But, then again, I fully expect to be shown wrong in my delayering! 162.158.74.25 00:31, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

- Wouldn't the inconvenient new evidence be the justification for the backlash against the prevailing concensus, not the reason why the new evidence is ignored? I'm not going to try to explain this comic, I'm lost already. Barmar (talk) 00:46, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

- It was the backlash that ignored the new evidence. The new evidence wasn't adopted by the 'backlashers', as I read it, so couldn't be their justification. (Or at least that's how the conventional wisdom interprets it, which of course could be wrong!) 162.158.34.23 00:56, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

- I agree, and the first couple of paragraphs of the explanation are currently wrong in suggesting that the "prevailing consensus" is the one to which the researchers ignoring evidence ascribe. Instead we have a position that most scientists accept to be true and have done for some time ("prevailing consensus"), but this has inspired a revolt that is implied to be more emotively-driven than facts-based ("backlash") leading to revolt-inspired research ("has led researchers") uncovering evidence ("new evidence") which did not fit the revolting researchers' preconceived ideas ("inconvenient") and has therefore not been properly taken into account ("ignored"); however, this description of the situation is one that is generally assumed to be true, without critical thought or despite proof to the contrary ("conventional wisdom"), and Cueball is about to tell us why ("however..."). In truth, Cueball could be about to rebut any one of those things, but it is heavily implied to be the "conventional wisdom" that is in his view wrong, so there may actually be no prevailing consensus, or no real backlash, or no real research done because of that backlash, or no new evidence, or proof that that evidence could actually be useful to counter the prevailing consensus, or (and this again is most likely IMHO) it is wrong for people to assume that that the evidence was ever ignored. Therefore Cueball is about to support the revolting researchers, but only in rebutting the mainstream rebuttal accusing the rebutting researchers of failing to rebut contradictory evidence...172.69.223.169 10:05, 11 December 2023 (UTC)

- It was the backlash that ignored the new evidence. The new evidence wasn't adopted by the 'backlashers', as I read it, so couldn't be their justification. (Or at least that's how the conventional wisdom interprets it, which of course could be wrong!) 162.158.34.23 00:56, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

I impressed myself by correctly remembering that the author of "Structure of Scientific Revolution" was Thomas Kuhn. It was assigned reading in a philosophy of science class I took over 40 years ago, but I haven't had to think about it much since then. Barmar (talk) 00:43, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

Looking for a way to depict the Title Text: "The mainstream dogma sparked a wave of dogmatic revisionism, and this revisionist mainstream dogmatism has now given way to a more rematic mainvisionist dogstream." Too garish? 172.69.79.142 00:52, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

- I'm not typing color codes, but I figured it would make more sense to coordinate the color by compound word, not roots. So "dogma" would be one color, "mainstream" would be another, etc. And then "dogstream" would be two-tone. 172.70.178.11 09:47, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

- On that topic, I think the description for "rematic" should be changed to more clearly reflect the combination of "revisionist" and "dogmatic"; I don't think it implies any relation to "remake", "remix", "refurbish" or "recycle", even if the ultimate meaning is similar (and I'm not sure that's the case anyway). 162.158.90.161 17:27, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

...why is there a file of a chatgpt image of "ematic mainvisionist dogstream"?--Utdtutyabthsc (talk) 07:10, 19 January 2026 (UTC)

- The conversation you posted above ("Looking for a way to depict the Title Text: [...]"), that I've moved us down below (for it to still fit alongside), might have formed the primary reason. Though, IIRC, it was originally in the main Explanation page and maybe got moved here as "interesting artefact no longer wanted in the main bit". I think it's an interesting curiosity. Where it should be, I'm not sure, but it still makes me smile to see it. Would be a shame to 'lose' it entirely. (But also wouldn't want to encourage any more like it, either... I have that kind of ambivalence.) And there are far worse ChatGPT images out there... ;) 82.132.244.8 15:16, 19 January 2026 (UTC)

A simple explanation of "rematic mainvisionist dogstream" is that they are created by taking "re" from revisionist and replacing the "dog" from dogmatic which replaces the "main" from mainstream which then replaces the "re" of revisionist. Rtanenbaum (talk) 19:25, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

That's an excellent explanation, yet I'm still not sure I understand the comic. There may be just too many layers of meta. Barmar (talk) 16:22, 21 November 2023 (UTC)

Unclothed evidence would certainly be inconvenient, to say no more, in the puritanical Church of Scientific Dogma. 172.70.210.40 17:39, 21 November 2023 (UTC)